Loperamide, an over-the-counter anti-diarrheal drug (Imodium A-D), is back in the news, as the blog by FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb warned of adverse effects from high doses. Loperamide is an opioid agonist (it activates the opioid receptors) that is safe when taken at approved doses. “But when loperamide is abused and taken at extremely high doses, some of it can cross the gut lining, giving users an opioid like ‘high.’” Sometimes people report using as much as 100 times the recommended dose of 2-8 mg daily. Reportedly, 50-300 mg of loperamide may produce euphoria.

We’re aware that those suffering from opioid addiction see loperamide as a potential alternative to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms or to achieve euphoric effects. But at these very high doses, it’s also dangerous. We’ve received reports of serious heart problems and deaths, particularly among people who intentionally misuse or abuse high doses.

The above warning, posted on May 9, 2018, referred back to a FDA Drug Safety Communication Update from January 30, 2018. It said the FDA was working with manufacturers to limit the number of doses of loperamide in their packages and revise OTC labeling to warn of the danger of serious heart problems associated with high doses. OTC loperamide is currently approved in packages of 8 to 200 tablets, which can be sold in multipack of more than 1,000 two mg capsules at a time. If the drug is taken as prescribed, that is more than a three-year supply of the drug. One of the FDA’s recommended packaging changes to discourage abuse was for manufacturers to use blister packs. “Evidence suggests that reasonable packaging limitations and unit-of-dose packaging may reduce medication overdose and death.”

There have been expressed concerns that packaging changes would drive up the cost. However the FDA does not expect the steps they’ve taken to have much, if any impact on cost, “given that loperamide is available as a generic drug and manufactured by a range of competitors.” Commissioner Gottlieb said the FDA would carefully evaluate the impact their actions could have on the cost of loperamide.

We’re currently evaluating the maximal package size appropriate for OTC use, and plan to take into account data manufacturers provide on consumer use and needs; current OTC labeling and indications; the dose-response relationship of loperamide to cardiac events and known adverse event data; and importantly, the feedback of patients who rely on this medicine.

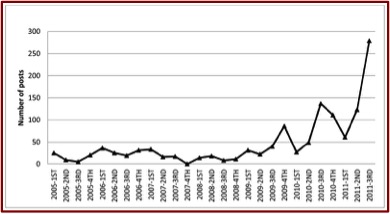

Concerns with adverse effects and abuse with loperamide have been appearing for a few years. In 2012, there was a web-based study of extra-medical use of loperamide. The intent of the researchers, Daniulaityte et al., was to collect user-generated content on one such website to assess emerging drug use practices and trends with loperamide. The first post on the website that mentioned loperamide appeared in 2005. By 2010-2011 there was a notable increase in discussions related to loperamide. See the following figure taken from the study.

Approximately 70% of the posts dealt with loperamide self-medication for opioid withdrawal. About 25% of the posts discussed the drug’s potential to produce euphoric or analgesic effects. Most of the posts about the drug’s use to manage withdrawal were positive (79%), while posts about using loperamide to get high or control pain were negative (69%). The most commonly discussed side effects were constipation, dehydration, and other types of gastrointestinal discomforts. “Some people also reported mild withdrawal symptoms from using loperamide for an extended period of time.”

Approximately 70% of the posts dealt with loperamide self-medication for opioid withdrawal. About 25% of the posts discussed the drug’s potential to produce euphoric or analgesic effects. Most of the posts about the drug’s use to manage withdrawal were positive (79%), while posts about using loperamide to get high or control pain were negative (69%). The most commonly discussed side effects were constipation, dehydration, and other types of gastrointestinal discomforts. “Some people also reported mild withdrawal symptoms from using loperamide for an extended period of time.”

A May 2016 New York Times article, noted how “Addicts Who Can’t Find Painkillers” turn to loperamide, “the poor man’s methadone.” They cited an online report, later published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine: “Loperamide Abuse Associated with Cardiac Dysrhythmia and Death.” The NYT article said overdoses had been linked to deaths or life-threatening irregular heartbeats in over a dozen cases in the previous eighteen months. “Some toxicologists argue that the sale of loperamide should be limited, much as the nonprescription drug pseudoephedrine was restricted a decade ago to help prevent the manufacturing of crystal meth.”

The lead author of the Annals of Emergency Medicine report, William Eggleston was quoted as saying: “We’ve seen patients who have been on loperamide for months at a time.” He added that while a subset of patients take it to get high another subset uses it to ease withdrawal symptoms. One 39-year-old male collapsed at home and was pronounced dead at the hospital. He had previously used buprenorphine to manage his opioid misuse disorder, but had been self-medicating with loperamide.

A Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report for the CDC by Eggleston et al. on November 18, 2016 noted the abuse of loperamide for its euphoric effect and as a self-treatment of opioid withdrawal was increasing. Eggleston and his colleagues found that the average daily dose of New York City residents who were abusing loperamide was 358 mg (their range was 34 to 1,200 mg). Prior opioid abuse was reported by 15 of the 22 abuse cases identified. Eight individuals reported previous treatment with methadone or buprenorphine. Heart abnormalities were found in eight to 15 individuals of the identified cases of abuse.

The researchers also looked at loperamide abuse data reported to the National Poison Database System (NPDS). The average dose in this population was 196.5 mg of loperamide (the range was 2-1,200 mg). Cardiac problems were also found with some patients. Outcomes reported for 132 patients were coded as major (life-threatening symptoms or residual disability) for 66 individuals (50%); four deaths were reported. “These cases support the reported association between loperamide abuse and cardiac toxicity.”

At a 2015 Clinical Toxicology Conference, Eggleston and two others presented a poster that described, “a case of buprenorphine induced acute precipitated withdrawal in a patient presenting with loperamide toxicity.” At the time, to their knowledge, withdrawal had not been reported with loperamide abuse. A 30 year-old male was seen at the hospital after passing out. Tests indicated he had some heart irregularities, but he left against medical advice. He was later found without a pulse and not breathing. He was given CPR and readmitted to the hospital.

Within 24 hours of his readmission, he complained of withdrawal symptoms and was given 12 mg of buprenorphine for the withdrawal. “He became agitated and combative with hallucinations.” He had to be resuscitated, sedated with propofol and intubated. The researchers said toxicologists should be aware of the increasing trend of loperamide abuse. Further, administering high-dose buprenorphine “in patients actively intoxicated with loperamide can acutely precipitate opioid withdrawal.”

The FDA Commissioner noted in his blog article how several retailers have already responded to the FDA’s request. Walmart/Sam’s Club have limited online purchases of 200 count tablet products to a single package and moved the sale of bundled products at Sam’s Club behind the pharmacy counter. Amazon has taken steps to address the FDA recommendations and eBay intends to do the same. Several manufacturing companies have committed to implementing the FDA packing changes or purchasing safeguards.

But the FDA actions come too late for a Western Pennsylvania man who died in November of 2017. When the Allegheny County medical examiner finally revealed in March of 2018 that the cause of the man’s death was from an overdose of loperamide, several media sources picked up the story, including the Daily Mail from the United Kingdom, the Miami Herald, the New York Post, and local Pittsburgh news outlets such as the Trib Live. I’m not sure his family will get much comfort from the FDA actions, but I hope rapid implementation of the recommendations will limit the number of future loperamide overdoses and other adverse events.