An article in The Morning Call, a newspaper for Allentown and the Lehigh Valley area of Pennsylvania, announced that a local company, the Lehigh Center for Clinical Research, would be conducting clinical trials for two pharmaceutical companies to gain FDA approval for modified versions of ketamine as a treatment for depression. The psychiatrist running the trials said the drugs could hit the market in the next few years. He said: “It’s exciting and promising but I think we have to wait to see it used in the widespread population to know whether it’ll be safe and non-toxic.” I thought the safety and toxicity of a new drug was supposed to be assessed BEFORE the FDA approved its release into the wider population.

There have been waves of excitement and concern over the past few years about the development and use of ketamine and ketamine-like drugs to treat depression. Ketamine has been an FDA approved medication since 1970, where it was used as an anesthetic in the Vietnam War. It is classified as a Schedule III Controlled Substance by the DEA, meaning it has a potential for moderate to low dependence or high psychological dependence. Ketamine is also a recreational drug known as Special K because of its dissociative properties. “Due to the detached, dreamlike state it creates, where the user finds it difficult to move, ketamine has been used as a ‘date-rape’ drug.” See: “Falling Down the K-Hole” and “Family Likeness in Depression Drugs?”

The excitement over ketamine, as a treatment for depression, centers on its rapid relief of depressive symptoms; sometimes within hours of it being administered. But the effects fade rapidly and require frequent, repeated treatments. Currently ketamine is administered intravenously, similar to its use as an anesthetic. There is an intranasal spray version (Esketamine) in the works. See: “Psychedelic Depression,” Ketamine to the Rescue?,” and Ketamine Desperation.”

The clinical trails being done by the Lehigh Center for Clinical Research would appear to be for Esketamine, by Janssen Research and Development, and Rapastinel, by Allergan. While Esketamine is a nasal spray, Rapastinel is administered by weekly IV injections. Both are currently in Phase 3 clinical trials. This involves randomized, double blind testing in several hundred to several thousand patients. Upon successful completion of their Phase 3 trials, a pharmaceutical company can request FDA approval for marketing their drug. Somewhere around 70 to 80 percent of drugs that make it to Phase 3 are eventually approved.

Although Esketamine and Rapastinel are similar to ketamine in several ways, they are still distinct NMEs (new molecular entities), patented by their respective pharmaceutical companies. Ketamine was first developed in the 1960s and has been off patent for decades, meaning there is no profit in Pharma companies pursuing ketamine-based treatment for depression. But since ketamine is an FDA approved drug, it can be used off label to treat depression. And there are a growing number of ketamine treatment facilities around the U.S. and Canada that do just that.

Earlier in 2017 All Things Considered on NPR featured a story on the off-label use of ketamine to treat depression, “Ketamine for Severe Depression.” Psychiatrist Gerard Sanacora said over 3,000 patients have treated at dozens of clinics with ketamine for depression. He has personally treated hundreds of people with low dose ketamine. Sanacora said when he is asked how he can offer it to people on the limited amount of available information and without knowing the potential long-term risk, he responds “How do you not offer this treatment” to individuals likely to injure or kill themselves, who have unsuccessfully tried the standard treatments?

Sanacora and others authored “A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders” that was published in JAMA Psychiatry in April of 2017. They noted how several smaller studies have demonstrated the ability for ketamine “to produce rapid and robust antidepressants effects in patients with mood and anxiety disorders that were previously resistant to treatment.” It also cautioned that while ketamine may be beneficial to some patients, “it is important to consider the limitations of the available data and the potential risk associated with the drug when considering the treatment option.”

Zorumski and Conway published “Use of Ketamine in Clinical Practice” in the May 2017 issue of JAMA Psychiatry. They also noted the increasing evidence from small studies that ketamine has rapid antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression. They commented how ketamine is having a major effect on psychiatry. “If clinical studies continue to support the antidepressant efficacy of ketamine, psychiatry could enter an era in which drug infusions and deliveries with more rapid responses become common.” They indicated the cautions of Sanacora et al. were noteworthy and should be emphasized.

Because of the limited data to guide clinical practice, these limitations extend to almost every recommendation in the consensus statement, including, perhaps most importantly, patient selection. The bulk of the literature describes the effects of ketamine in patients with treatment-refractory major depression. The definition of treatment-refractory major depression and where treatments such as ketamine fall in the algorithm for managing treatment-refractory depression remain poorly understood. . . . It is unclear whether patients with depression that is not treatment-refractory or patients with other psychiatric illnesses are appropriate candidates for ketamine treatment, and extreme caution must be exercised in patients with psychotic or substance use disorders.

So then comes the Short et al. study in the journal Lancet Psychiatry in July 2017, “Side Effects Associated with Ketamine Use in Depression.” It was the first systematic review of the safety of ketamine in the treatment of depression. After searching MEDLINE, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Databases, they identified 60 out of 288 articles that met their inclusion criteria. “Our findings suggest a selective reporting bias with limited assessment of long-term use and safety and after repeated dosing, despite these being reported in other patient groups exposed to ketamine (eg, those with chronic pain) and in recreational users.”

Science Daily reported that the lead author for the study said there were major gaps in the research literature that should be addressed before ketamine was widely used as a clinical treatment for depression. “Despite growing interest in ketamine as an antidepressant, and some preliminary findings suggesting its rapid-acting efficacy, to date this has not been effectively explored over the long term and after repeated dosing.” Given that ketamine will likely involve multiple, repeated doses over an extended time period, “it is crucial to determine whether the potential side effects outweigh the benefits to ensure it is safe for this purpose.”

Commenting on the Short et el. Study for Mad in America, Peter Simons also noted the expressed concern with the selective reporting bias and a limited assessment of long-tem use and safety after repeated dosing. Researchers are generally careful to report safety and side effect data on studies of ketamine used recreationally or for chronic pain. However, depression research tended to ignore the safety and side effect concerns with ketamine, often not reporting such issues at all. “Most people receiving ketamine had acute side effects.” Studies that did report adverse events said that after acute dosing, patients in ketamine treatment reported more frequent side effects.

Common side effects led a number of patients to withdraw from the study. Suicidal thoughts were common and there was one suicide attempt reported. Previously reported potential long-term adverse effects from ketamine include: urinary tract problems, liver toxicity, ulcerative cystitis, neurocognitive deficits and memory problems, and dependence or addiction. Some of the many additional side effects that were reported included:

- Worsening mood

- Anxiety

- Emotional blunting

- Psychosis

- Thought disorders

- Dissociation

- Depersonalization

- Hallucinations

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Decreased blood pressure

- Decreased heart rate

- Heart palpitations/arrhythmia

- Chest pain

- Headaches

- Dizziness

- Unsteadiness

- Confusion

- Memory loss

- Cognitive impairment

- Blurred vision

- Insomnia

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Crying/tearfulness

Because of the extensive list of potential adverse effects, as well as the unknown possibility for harm from long-term use, the authors of Short et al. recommended large-scale clinical trials with multiple doses of ketamine. Long-term follow up to assess the safety of long-term regular use was also recommended. “As it stands, the safety of ketamine treatment for depression is unknown—and that is largely due to inadequate and biased reporting of safety issues.”

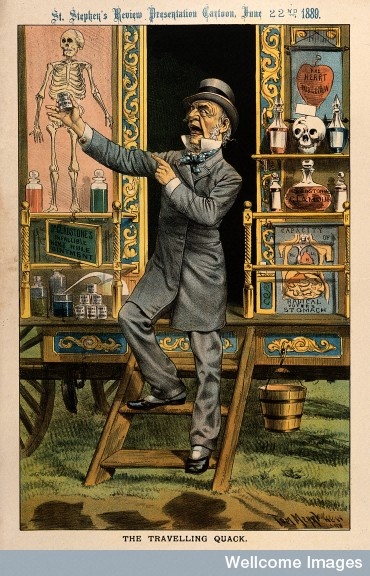

I hope that these concerns are seriously considered and factored into the FDA’s assessment process for approving Esketamine and Rapastinel. Otherwise, the real safety and toxicity assessment of these drugs will be done on the first wave of depression sufferers prescribed the new drugs for treatment-resistant depression. Given the short length of clinical trials, the long-term effectiveness and impact on a patient’s quality of life, including potential misuse of the drugs, will not be clear for either Esketamine or Repastinel until Phase 4 Post Marketing Surveillance Trials are completed … after the drugs are on the market. Will they live up to their therapeutic promise or become another example of the Pharma patent medicine show?