May came and went with the vast majority of people in the U.S.—including me—being totally unaware that it was Hepatitis Awareness month. May 19th was National Hepatitis Testing Day. Hepatitis-C (HCV) is the most common form of viral hepatitis in the U.S. The number of new HVC infections almost tripled between 2010 (850) and 2015 (2,436). We need to be more aware of this disease and its treatment because it kills more Americans than any other infectious disease, including HIV. Yes, more people than HIV. CDC data indicated nearly 20,000 Americans died from hepatitis-C-related causes in 2015; and the majority of those deaths were people 55 and older.

“Because hepatitis C has few symptoms, nearly half of people living with the virus don’t know they are infected and the vast majority of new infections go undiagnosed.” The highest rate of new infection occurs among 20- to 29-year-old injection drug users. But ¾ of the 3.5 million Americans living with hepatitis C are baby boomers born between 1945 and 1965. They are six times more likely to be infected with hepatitis C and are at much greater risk of dying from the virus. Around ½ of all the deaths from HCV in 2015 occurred within this age range. You can read the three CDC press releases this information was taken from here, here and here.

These press releases highlighted information in report, “A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C” that suggested a strategy to eliminate both as public health problems by 2030. Immunization against hepatitis B (HBV) can prevent 95% of infections. There is no vaccine against HCV, but there are anti-viral drugs that can cure hepatitis C, but the costs are prohibitive. The introduction of the report said:

There is no longer any reason to disregard these diseases. There is an effective vaccine to prevent hepatitis B, advances in treatment can prevent most deaths in those chronically infected with HBV, and hepatitis C is now curable with a short course of easily tolerated treatment.

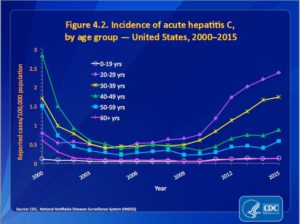

CDC data on HCV suggested that 75% to 85% of newly infected adults and adolescents develop chronic infections. From 2000 to 2002 incident rates for acute HCV decreased for all age groups except for persons aged 0-19. Then the rates remained fairly steady from 2002 through 2010. Between 2010 and 2015 rates increased for persons in all but the oldest (<60 years old) and youngest (0-19 years old) age categories. The largest increase was among persons between 20 and 29 years old. See the following graph of the reported CDC data.

The drug companies charge between $60,00 and #90,000 for a 12-week course of treatment. This is way out of proportion to the cost of treatment in third world countries. Eliminating HCV as a public health problem by 2030 would require mass treatment, but none of the direct-acting agents come off patent before 2029. In the long run, HCV treatment is cost-effective, but doesn’t address the upfront costs charged by pharmaceutical companies for their drugs. So the cost of antiviral that cure HCV is a major obstacle.

The drug companies charge between $60,00 and #90,000 for a 12-week course of treatment. This is way out of proportion to the cost of treatment in third world countries. Eliminating HCV as a public health problem by 2030 would require mass treatment, but none of the direct-acting agents come off patent before 2029. In the long run, HCV treatment is cost-effective, but doesn’t address the upfront costs charged by pharmaceutical companies for their drugs. So the cost of antiviral that cure HCV is a major obstacle.

These drugs have strained the budgets of public and private payers alike. Faced with the unenviable task of allocating scarce treatment, payers gave first priority to the sickest patients, those at most immediate risk of death. Many also imposed sobriety restrictions, fearing the risk of re-infection in active drug users too great to justify the expense of treatment. Such restrictions have met with criticism. Overt drug rationing offends the American public, but it is difficult to know how else to act in the face of such high prices.

One of the recommendations of the report is for the federal government to purchase the rights to one of the direct-acting antiviral treatments for use with neglected populations such as individuals on Medicaid, in prisons and those treated through the Indian Health Services. This would be a voluntary transaction between the government and the pharmaceutical companies providing the antivirals. The company would be guaranteed reasonable compensation and the licensed drug would only be used in the limited markets (noted above) the companies aren’t now reaching.

Calculations show that the licensing rights should cost about $2 billion, after which states would pay about $140 million to treat 700,000 Medicaid beneficiaries and prisoners. By comparison, the status quo would cost about $10 billion over the next 12 years to treat only 240,000 similar patients.

Critics of the strategy suggest it sets a dangerous precedent by having the government negotiating a license for a costly medicine. Actually, it seems that the federal government’s reluctance to interfere with the pharmaceutical industry may have emboldened it to initially set the extremely high prices foe HCV drugs.

The Senate Finance Committee’s 2014 investigation into the pricing of sofosbuvir [Solvadi] concluded that Gilead had deliberately elevated the price in an effort to raise the market floor, ensuring continued high prices for all future hepatitis C treatments. Action now might discourage other companies from pursuing this strategy in the future.

A CNN article on the report by Susan Scutti noted the hardest hit areas of the U.S. in terms of new HCV infections are parts of Appalachia and rural areas of the Midwest and New England. Several states, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Tennessee and West Virginia have infection rates that are two times or more than the national average. Ten other states have rates above the national average: Alabama, Montana, New Jersey, Noth Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington and Winconsin.

There is a website, HepVu, presented by the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, which partnered with Gilead Sciences, the original price gauging pharmaceutical company with its antivirals, Solvadi and Harvoni. The original drug development research into Solvadi was done at Emory. Despite the Gilead partnership, HepVu has some helpful information, including an interactive map by state in the U.S. The home page stated there are an estimated 3.9 million people in the U.S. living with past or current hepatitis C infection. You can look up each state’s individual profile.

For example, within my home state of Pennsylvania, there are an estimated 142,100 people living with Hepatitis C. The HCV mortality rate is 4.952 per 100,000 persons, with 629 hepatitis C deaths in 2014. In West Virginia, there are an estimated 24,400 people living with Hepatitis C. The HCV mortality rate is 5.9 per 100,000 persons, with 110 hepatitis C deaths in 2014. In Ohio, there are an estimated 119,100 people living with Hepatitis C. The HCV mortality rate is 4.9 per 100,000 persons, with 567 hepatitis C deaths in 2014. Go to the site and check out your own state’s data.

The outrageous price of medications to treat hepatitis C illustrates how pharmaceutical companies are feeding off of the problems they had a hand in creating. The rise in hepatitis C infections comes as a result of increased IV drug use, which resulted from the prescription opioid epidemic leading individuals to switch from prescription opioids to heroin. And the public health problems with hepatitis C will only get worse since it often goes undiagnosed for years. It’s a public health time bomb.

The above recommendation to have the federal government negotiate a license for one of the existing Hepatitis C treatments is a good one. It just might deter other companies from trying the same pricing trick in the future with other medications. But the cozy lobbying relationship between Pharma and Congress could prevent it.

For more on this issue, see: “Is There No Balm in Gilead?,” “I Guess I’m a Little Bit Socialist,” “Riding the Hep C Gray Train,” “Impeccable Timing” and “Hepatitis Hostages.” Also see “Pharma Companies Hunt in Packs” for more information on the issues of the high cost of prescription drugs.