“When Columbus lived, people thought the earth was flat.” That was supposedly what everyone believed during the Middle Ages and what the brave Columbus disproved by sailing west from Spain to get to the East Indies. As the legend goes, Columbus was one of the few who believed the earth was round. The trailer for the 1992 Ridley Scott film, 1492: Conquest of Paradise,” illustrates the common belief that in a time of “rigid faith and restless doubt”, Columbus challenged the forces of fear and ignorance. Except it seems that saying the Middle Ages believed the earth was flat, is itself mythical.

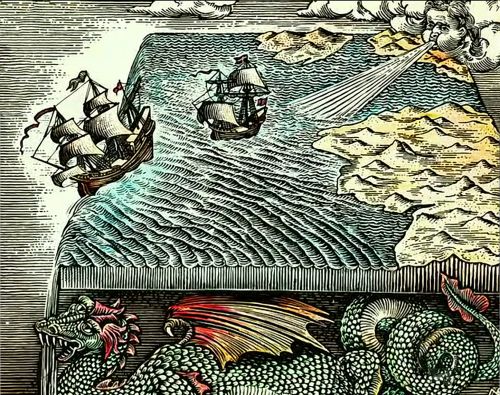

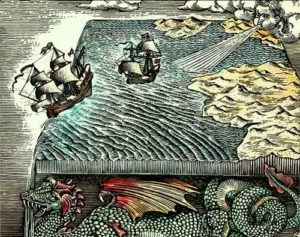

Yet this myth has been a “truth” taught to American school children for over 100 years. Emma Miller Bolenius, who wrote several schoolbooks for American children, wrote the above quote in a 1919 text. She said people in Medieval times believed the Atlantic Ocean was full of monsters and fearful waterfalls that their ships would plunge over and be destroyed. “Columbus had to fight these foolish beliefs to get men to sail with him. He felt sure the earth was round.” In reality, it was a biography of Columbus by Washington Irving, the American author of the famous short stories, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle,” who first introduced this idea to the world.

The Middle Ages was supposed to have been a time of ignorance and backwardness. People in these so-called “Dark Ages” were thought to be so ignorant (or deceived by Catholic priests) that they believed the earth was flat. To say something today is “medieval,” is to slur it as backward or ignorant. Belief in a flat earth is equated with willful ignorance, while an understanding that the earth was spherical, as with Columbus, was a sign of the beginning of modernity. This is an almost an axiomatic view that many people today take for granted.

But in her essay on the belief “That Medieval Christians Taught that the Earth Was Flat,” Lesley Cormack said that early church fathers such as Augustine (d. 430), Jerome (d. 420) and Ambrose (d. 397) all agreed that the earth was a sphere. Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274), Roger Bacon (d. 1292) and Albertus Magnus (d. 1280) also believed in a round, spherical earth. She said: “From the seventh century to the fourteenth, every important medieval thinker concerned about the natural world stated more or less explicitly that the world was a round globe.” Many of these even incorporated Ptolemy’s astronomy and Aristotle’s physics into their work.

Cormack said that in the nineteenth century, scholars who were interested in “promoting a new scientific and rational view of the world.” They claimed that medieval churchman suppressed the belief of the ancient Greeks and Romans that the world was round. One of these individuals was the American historian and scientist John William Draper, who believed that Columbus ushered in modernity by proving the earth was round.

Cormack began her essay with a quote from Draper’s 1874 book History of the Conflict between Religion and Science. In chapter six of his book, Draper said the traditions and policy of Roman Catholic Church “forbade it to admit any other than the flat figure of the earth.” The belief in a flat earth continued until “the question of the shape of the earth was finally settled by three sailors, Columbus, De Gama, and, above all, by Ferdinand Magellan.”

In the Introduction to Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion, Ronald Numbers pointed out how Draper focused much of his condemnation upon the Roman Catholic Church partly because it then composed the majority of Christendom, partly because its demands were the most pompous, and partly because it sought to enforce those demands by civil power. But there was a more personal reason that seems to have influenced Draper in his prejudicial view of the history of the Roman Catholic Church and scientific progress. Draper never mentioned it publically, and it only came to light after his death.

Drawing from a biography of Draper by Donald Fleming, John William Draper and the Religion of Science, Numbers related a conflict that arose between Draper and his sister Elizabeth, who had converted to Catholicism. For a time, she lived with the Drapers. When her eight-year-old nephew William, one of the Draper’s children, was dying, she hid one of his favorite books, a Protestant devotional, “which he cried for.” After William’s death, she laid the devotional on Draper’s breakfast plate. “He met this cool challenge by ordering her out of the house.” He never forgave her. Numbers concluded Draper blamed the Vatican “for her unChristian and dogmatic behavior.”

Another often repeated medieval myth is that the church of the Middle Ages prohibited human dissection. As Katherine Park related, the myth “That the Medieval Church Prohibited Human Dissection” had its classic statement in another nineteenth century church and science polemic by Andrew Dickinson White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. White said a serious stumbling block to the beginnings of modern medicine and surgery was a belief in “the unlawfulness of meddling with the bodies of the dead.” He said Augustine held anatomy in abhorrence, while it seems Augustine actually had a more nuanced opinion.

In The City of God Augustine discussed “The Blessings with Which the Creator has filled this life.” After discussing the blessing of the mind, by which the human soul becomes capable of knowledge and receiving instruction, he turned to the gift of the body. Augustine said while every part of the body had been created for utility, they also contributed something to its beauty. Reflecting then current medical knowledge, he said this would be all the more apparent if we could see beyond the surface. No one, Augustine thought, could discover that beauty and utility. “For as to what is covered up and hidden from our view, the intricate web of veins and nerves, the vital parts of all that lies under the skin, no one can discover it.”

Anatomists, who dissect bodies of the dead, and sometimes sick persons who die under their knives (surgery?) have “inhumanly pried into the secrets of the human body.” It seems Augustine objected to those who disregarded that the human body was part of the image of God in their pursuit of knowledge, treating it like the body of a beast. He questioned the wisdom of seeking to discover the utility of parts of the body like the web of veins and nerves, which he thought could never be done. He abhorred dissection when it treated the human body like that of an animal, disregarding its intimate connection to the soul in the image of God. Katherine Park suggested another possibility here: Augustine saw the fascination with dismembering corpses as an unhealthy curiosity about matters irrelevant to salvation.

In chapter nine where White discussed “The Scientific Struggle for Anatomy,” he acknowledged that there were pockets of medical science where dissection was permitted, particularly at the greater universities “which had become somewhat emancipated from ecclesiastical control.” White singled out Andreas Vesalius, often referred to as the father of modern human anatomy, as a particular hero in this war between science and religion. White said Vesalius was charged with dissecting a living man and directed by the Inquisition to undertake a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, “as the great majority of authors assert,” to atone for his sin of doing such a dissection. He was shipwrecked and died on his return.

Modern biographers dismiss this as a myth; Vesalius was not on pilgrimage due to pressures of the Inquisition. The story originated with Hubert Lambert, a diplomat under Emperor Charles V and then under the Prince of Orange. Lambert claimed in 1565 that Vesalius had performed an autopsy on an aristocrat in Spain while the heart was still beating, which led to the Inquisition’s condemning him to death. Philip II had the sentence commuted to a pilgrimage. “The story re-surfaced several times over the next few years, living on until recent times.” See the Wikipedia entry on Andraes Vesalius for more information.

Park said human dissection was not practiced with any regularity before the end of the thirteenth century “in either pagan, Jewish, Christian, or Muslim cultures.” Greek and Roman avoidance of dissection seems to be due to the belief that corpses were ritually unclean. While early Christian culture rejected the idea of corpse pollution and did not prohibit its practice in the early Middle Ages, “there is no evidence for its practice.” The above-discussed disapproval by Augustine may have played a role, but it was also influenced by the generally undeveloped state of medical learning “after the fall of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century.”

The myth of the medieval church prohibiting human dissection is as strong now as when it was first invented by John Dickinson White. The late U.S. Senator, Arlen Spector, referred to it as he spoke in favor of S. 2754, the Alternative Pluripotent Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act of 2006. He cited a 1299 papal bull by Pope Boniface VII, wrongly saying it had banned the practice of cadaver dissection. “This stopped the practice for over 300 years and greatly slowed the accumulation of education regarding human anatomy.”

It seems that Mondino de’ Liuzzi didn’t get the memo, because he produced the first known anatomy textbook based on human dissection in 1316. It remained “a staple of university medical instruction through the early sixteenth century.” Dissection was confined to Italian universities and colleges for a time. But by the late fifteenth century it had spread to northern Europe, “and by the sixteenth century it was widely performed in universities and medical colleges in both Catholic and Protestant areas.”

The essays by Leslie Cormack and Katharine Park can be found in Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion, edited by Ronald Numbers.