Ancient Healing Rituals

I find it ironic that the rod of Asclepius is associated with the healing rituals of asclepions as well as modern medicine. Within the claims of psychiatry, the connection is certainly appropriate. While modern medicine as a whole has come a long way since then, it seems psychiatry still has a lot in common with the cultic healing rituals the apostle Paul saw practiced in Corinth.

Soon after he declared the unknown god at the Areopagus. (Acts 17:22ff), Paul left Athens for Corinth. He may have become impatient waiting for Timothy and Silas to return from Thessalonica, and just continued on with the next leg of their mission trip. They would catch up to him in Corinth, because Paul ended up staying there for eighteen months.

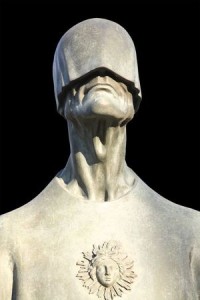

Corinth was about fifty miles southwest of Athens, so it is likely Paul entered the city from the north on the Lechaeum road. Just inside the northern city wall Paul would have passed by a temple to Asclepius, the Greek god of healing. The cult of Asclepius began around 350 bc and his temples, called acelepions, became popular sites for pilgrimages and training in healing throughout the Mediterranean. Both Hippocrates and Galen were said to have studied medicine at asclepions.

Asclepius was the son of the Greek god Apollo and the woman Coronis. After Apollo killed Coronis for her infidelity, he gave the infant Asclepius to the centaur Chiron, who raised him and taught him the art of medicine. Alternately, Greek mythology says that as a result of a kindness he rendered to a snake, the snake taught Asclepius the secret knowledge of healing. Ancient Greeks believed snakes were sacred beings of wisdom, healing and resurrection. The rod of Asclepius, a snake-entwined staff, remains the symbol of medicine today.

Asclepius became famous for his skill as a healer, surpassing even Chiron and Apollo. He was so proficient with his healing arts, that he was said to be able to bring his patients back to life from the brink of death—and beyond. This led Zeus to kill Asclepius for reasons that ranged from population control (too many humans), to complaints from Hades about not having enough spirits in the underworld. Zeus then raised Asclepius from the dead and made him immortal, extracting a promise from him to never raise another human from the dead without getting permission from Zeus first. This is Greek mythology at its dysfunctional finest.

As Paul passed by the asclepion, he would have seen the sick and infirm coming and going from the temple. They slept there overnight, believing that Asclepius would come to them in a dream to provide healing or prescribe medication for their illness. Once worshipers experienced their healing, they would commission votive offerings representative of the body part that was healed and present these offerings to the temple. So the Asclepius cult provided the apostle with rich, local imagery to illustrate the unity of Christians that Paul would later argue was needed in his letter to the Corinthians.

Some scholars said that early Christians saw Asclepius as “their strongest enemy,” and “the most dangerous antagonist” to Christ. Justin Martyr pointed to a connection between Jesus and Asclepius when he wrote that there were analogies to the works attributed to the Christ in Greek mythology, including those of healing by Asclepius. “And in that we say that He made whole the lame, the paralytic, and those born blind, we seem to say what is very similar to the deeds said to have been done by Aesculapius.” So it’s not hard to imagine Paul using the customs of this cult for his initial presentation of the Christian gospel to the Corinthians, just as he used the example of an altar to an unknown god in Athens (Acts 17:23). J. D. Charles, in the Dictionary of New Testament Background, said:

Imagery abounds from Corinthian life as mirrored in Paul’s letters to the church in Corinth. Polished bronze mirrors, the theater, the proconsul’s judgment seat, agriculture, architecture and building, the Isthmian Games and local temples all add color to Pauline correspondence. Given the apostle’s emphasis on unity and diversity among different members of Christ’s body, it would be natural for him to conceive of unity and diversity in terms of the local Asclepius temple in Corinth. In 1 Corinthians 12:12–31 Paul mentions ears, eyes, hands and more honorable and less honorable parts of the body. It is plausible that he is alluding to the huge number of clay figurines of dismembered body parts scattered throughout the Asclepion that represented afflicted members cured by the deity. In Paul’s day, these terra cotta offerings consisted of heads, hands and feet, arms and legs, breasts and genitals, eyes and ears. Against the background of the Asclepion the Corinthian believers would have been reminded in the most vivid of terms of what they should not be—divided, dead, unconnected members of the body.

Charles went on to illustrate the wealth of cultural images and allusions used by Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians. Paul used the metaphor of the temple in 1 Corinthians 3:16-17 and 6:19-20. He used a building metaphor in 1 Corinthians 3:10 ff (see “The Architektōns of God)”. He quoted Menander in 15:33, saying: “Bad company corrupts good morals.” He toyed with the sense of knowledge or gnōsis in 8:1-13. There were others as well. But the one of our particular interest here is the body metaphor in 12:12-27, most likely borrowed in part from the religious practices of the Asclepius cult.

In the Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, Ronald Fung indicated how the body metaphor was unique to Paul in the New Testament writings. Rather than attributing it just to the votive offerings at the Corinthian asclepion, he thought it was the result of the interplay of several sources. Fung suggested Paul combined the Stoic comparison of the state to a body of interdependent members (see “Ancient Star Wars Philosophy”) with the Hebrew concept of “corporate personality.” Here he referenced the notion of all men and women being born “in Adam” and all believers having new birth “in Christ” (Romans 5:12-21; 1 Corinthians 15:22, 45).

A third idea behind Paul’s use of the body metaphor, according to Fung, was that of the solidarity between Christ and his people (see Mark 9:37; Matthew 18:5; 25:40 and Acts 9:4). Certainly the use of the body metaphor with Paul’s discussion of the Lord’s Supper in First Corinthians 11:17 ff ties in with this third idea. An intriguing fact of the Corinthian asclepion is that when it was renovated in the first century, three dining rooms were added to the east side of the temple courtyard. Like parish halls in modern churches, these dining rooms were used for social events as well as religious ones. Could they have been the space used by the church in Corinth for its celebration of the Lord’s Supper? Or perhaps Paul’s description of the excesses at Christian celebrations of the Lord’s Supper were being compared to the eating behavior at religious and social gatherings in the asclepion dining rooms.

If so, he would have been saying that even if you avoid using the asclepion for your gatherings, your behavior is just as bad. Just as a devotee of the asclepion must perform their ritual properly for healing, when you eat and drink the Lord’s Supper in an unworthy manner, you eat and drink judgment upon yourself (1 Cor. 11:29). I think that in addition to the ideas favored by Ronald Fung, Paul had the cult of Asclepius in mind when he spoke of the body metaphor in First Corinthians. Just as he used an Athenian altar to an unknown god as an illustration in his address at the Areopagus, Paul would have seen how the Asclepius cult practices could be used to speak of how “we who are many are one body” (1 Corinthians 10:17).

I had intended to just reflect on Paul’s use of the body metaphor in his first letter to the Corinthians, but the association of Asclepius and modern psychiatry intruded into my thoughts. In the asclepions medical healing rites were administered as cultic healing rituals. Modern psychiatry often dispenses its own healing rituals as medical healing rites.