While driving home, I caught the end of an NPR program, “This American Life,” with Ira Glass. I later learned the feature I was listening to was the third segment of a program they titled “The Leap.” The interview was of a woman, Tina, who came into Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) at the age of 13. As an adult, she began to question whether or not she was truly an alcoholic, decided she wasn’t, and now drinks socially. Still not really intrigued? Her story of getting sober at 13 is in the A.A. pamphlet, “Young People and A.A.”

So what about Tina? How did she grow out of alcoholism; or are we waiting for the “yet”—the inevitable slide back into drinking alcoholically? The above link for “The Leap” will take you to a page to either listen to the broadcast or read a transcript of the program. Tina’s segment, “The Wisdom to Know the Difference,” is the third of three in the broadcast and transcript.

For twenty years of her life she didn’t question that she was an “alcoholic.” Then she began to wonder what would happen if she drank. “Asking herself, should I take a drink, was basically asking, should I turn my back on what I believed about myself for 20 years?”

As a child, Tina’s parents had been part of The Children of God, a cult or “new religious movement.” In what seems to have been normal for members at the time, they moved around a lot—four different countries before she was three years old. Her life with The Children of God would have been full of dysfunction, abuse and trauma. This is speculation on my part from easily obtained information on The Children of God, especially the stories of former cult members. She would have been primed to become a preteen who turned to alcohol and drugs.

She was eventually sent to a girl’s group home, where she lived until she graduated from high school. It was while she was there that she began attending A.A. meetings. She became a popular A.A. speaker—“the girl who got sober when she was 13, and could tell the hell out of her story.” By the time she was 33, Tina had been married for several years. She was a columnist and political commentator, “a long way from the miserable, angry girl she’d been who dropped out of school and spent her time drinking and smoking pot with the older kids.”

So when she began to wonder if she could drink alcohol socially, she talked it over with her husband, who was supportive of whatever she decided. She discovered that she could drink socially, and now believes that: “I’m not an alcoholic. Not by any measure.” No personality changes from drinking; no gradual increase in how much she drinks.

So how does a non-alcoholic child come to believe that she’s an alcoholic? Tina makes sense of what happened to her this way. She went to her first A.A. meeting for something to do. While she was there, she found she could relate to what other people at the meeting said. They had been rejected by family too. They had felt trapped and furious and desperate too. People told her they used to be exactly like her.

There was no other way of explaining at the time. And it wasn’t until, I mean, this is very recently, there was no way for me to figure out why I kept on getting locked up. Why I kept on being sent away. Why my mother was fuming at me.

If she was an alcoholic, she could make sense of her life—and she could fix the problem. A.A. gave her a new life, with goals, discipline, a belief system. And most importantly, people to relate to when things were bad or when they were good.

It’s really liberating to find your people. To find people who you relate to. To find people that ask you to come back. And that was what I experienced. I didn’t have people asking me to come back. . . . And being able to feel true happiness, just feeling like I was OK, and there was no crisis, that was what I learned in Alcoholics Anonymous. That is the irony, right? I’m not an alcoholic, but my life was saved by AA.

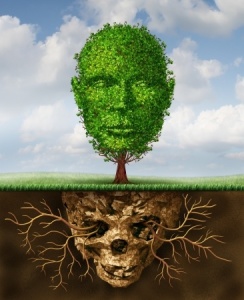

Tina’s story illustrates the elasticity of terms like “addict” and “alcoholic.” In one sense it also challenges the sense of the saying, “Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.” But it doesn’t negate the validity of 12-Step recovery organizations like A.A. Here’s why I think so. What Tina really grew out of was her addictive behavior.

The addiction researcher Carlton Erickson doesn’t like the terms “addiction” or “alcoholism.” He said in his book, The Science of Addiction, that they aren’t scientific. They are too broad, too vague and too easily misunderstood. He said he prefers the terms alcohol dependence or drug dependence, saying they are closer to what scientists mean when the terms alcoholism or addiction are used by nonscientists. Similarly, he prefers the term drug misuse to drug abuse, “because it more clearly places the responsibility for drug use on the person.”

Erickson’s distinctions become important when we turn to how drug users are diagnosed within the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Well, that is how they were diagnosed within the fourth edition of the DSM, when there was substance (or drug) abuse and substance (or drug) dependence. The current edition of the DSM, the fifth, has a continuum of substance use disorders, which confusingly combines two distinct types of substance use problems into one continuum.

Drug abuse (or misuse) is the intentional overuse of drugs “in cases of poor judgment, self-medication, overcelebration, and other situations where drugs can be harmful or illegal.” Drug dependence is “compulsive, pathological, impaired control over drug use, leading to an inability to stop using drugs in spite of adverse consequences.” Erickson then said:

Anyone who has a drinking problem and who wants to stop is welcomed into their group [A.A.] and declares, “I’m an alcoholic.” There is no formal distinction between “abusers” and “dependents” in community A.A. meetings. . . . A proper diagnosis is not important when people are trying to find a way to stop drinking. If successful, they are much better off than before they worked the fellowship program” (p. 20).

An individual like Tina can use A.A. to stop abusing alcohol, as described by Erickson, and then turn her life around. She would identify as an “alcoholic” during the time she was an active member of A.A. But, applying A.A.’s Third Tradition (which says you are a member of A.A. if you say you are), if she no longer had the desire to stop drinking, if she does not see herself as a member of A.A., then in that sense, she’s no longer an alcoholic. Diagnostically, it would seem she was an alcohol abuser who grew out of the need to self-medicate because of the dysfunction of her early life.