Are Antidepressants Worth the Risks?

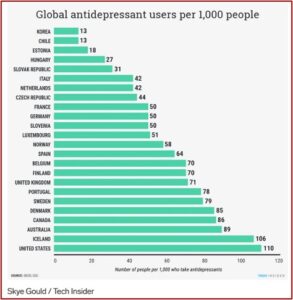

Business Insider published an article in 2016 with some startling statistics on the global use of antidepressants by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). They discovered that in all 25 countries, antidepressant use was increasing. “The increase in antidepressants consumption has spurred an ongoing debate [about] whether antidepressants are overprescribed (medicalization) or underprescribed (poor access to treatment).” The U.S. was not included in the OECD analysis, but if it had been, it would have topped the list, as the following chart indicates.

The chart suggested that 11% of Americans, 110 per 1,000 people, used antidepressants in 2016. But the use of antidepressants is not an accurate indicator of depression rates. In the U.S., for example, only about one third of people with severe depression take an antidepressant. Yet the use of antidepressants is rising.

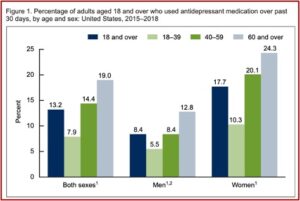

The CDC reported that 13.2% of American adults used antidepressants in the past 39 days. Antidepressant use increased with age, from 7.9% among adults aged 18 to 39 to 19.0% for those aged 60 and over. Use was higher among women than men. Almost one-quarter of women aged 60 and over (24.3%) took antidepressants. See the follow figure from the CDC data brief.

The History of Antidepressants

Given the increased use of antidepressants globally and within the U.S., it seems some awareness of the history of antidepressants and their potential side effects would be helpful. In an article for Psychology Today, Mark Ruffalo gave a brief history of antidepressants in his discussion of Prozac (fluoxetine). He saw the introduction of that drug in 1987, the first SSRI, as a “game changing” event in the history of psychiatry.

The search for a drug to specifically target depression began in the 1950s and led to the monoamine hypothesis of depression. The monoamine hypothesis suggested depression was associated with a deficiency in the monoamine systems of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine. In the 1960s and 1970s, psychiatry believed norepinephrine played a central role with affective disorders. “Serotonin’s role was minimized and seen only as ancillary to norepinephrine.”

Tricyclic antidepressants such as Tofranil (imipramine) and Elavil (amitriptyline) were brought to market. They block the reabsorption (reuptake) of serotonin and norepinephrine, increasing the levels of these two neurotransmitters in the brain. But there are side effects such drowsiness, blurred vision, constipation, dry mouth, light headedness, sexual problems, and others. Given the multiple adverse effects, tricyclics were only prescribed for the more severe cases of depression. But that all changed with Prozac.

In the early 1970s, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly began to investigate the possibility of developing an antidepressant drug that avoided the potential cardiovascular risks associated with some of the earlier tricyclic antidepressants (like imipramine and amitriptyline). The Lilly team, which included the Hong Kong-born biochemist David Wong, synthesized several chemicals derived from an antihistamine called diphenhydramine (found in Benadryl and over-the-counter sleeping aids like Tylenol PM). Wong, who was familiar with European research implicating serotonin in mood regulation, encouraged the team to screen their newly synthesized chemicals for any that might selectively inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. On July 24, 1972, they found one [fluoxetine].

A few years later, Eli Lilly filed an application with the FDA to investigate fluoxetine’s potential to treat clinical depression. Ruffalo said initial expectations were modest. In December of 1987, fluoxetine, now branded as Prozac, received FDA approval. “Within a few months, Prozac sales outpaced the market leader Pamelor (a tricyclic), as physicians believed that Prozac was both safer and avoided the weight gain common with the tricyclics.” Prozac became the best-selling antidepressant of all time.

With Prozac’s mass success, a new type of depressed patient emerged: the mildly depressed. For hundreds of years, depression (historically termed melancholia), was considered a rare and serious disease, usually only observed in psychiatric inpatients. Because Prozac was so safe—and the risk of drug-drug interactions minimal—doctors began prescribing it to patients with milder symptoms, those to whom they might have hesitated to prescribe a tricyclic. Patients who would have been treated in psychotherapy instead started on Prozac. A biological revolution was well underway.

More SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) came to market. Zoloft (1991) and Paxil (1992) were followed by the release of the so-called SNRIs (serotonin-norepinepherine reuptake inhibitors) such as Effexor (venlafaxine, 1993) and Cymbalta (duloxetine, 2004). Pfizer, the manufacturer of Zoloft, spearheaded the claim in drug advertising that a “chemical imbalance” caused depression, which SSRIs like Prozac and Zoloft corrected.

In 1993, Peter Kramer published Listening to Prozac, which became a New York Times bestseller. In addition to lifting depression, he suggested these new drugs could be used as personality enhancers. “Kramer raised the possibility that, in addition to lifting depression, Prozac could also brighten a dull personality, assist an ambitious employee in climbing the corporate ladder, and make a shy person lively and outgoing.” Public interest in the drug piqued, and in 1993 sales increased 15%. At this point in time, SSRIs are the first-line pharmacotherapy for major depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder.

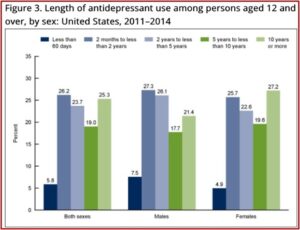

SSRI antidepressants are now one of the three most commonly used therapeutic classes of drugs in the U.S. And their long-term use has been steadily increasing as well. In 2014 the CDC reported that 68% of persons who used antidepressants had done so for 2 years or more; 19% between 5 and 10 years; and 25.3% had been using antidepressants for 10 years or more. See the figure below.

The Consequences of Overprescribing Antidepressants

The popularity of antidepressants has led to concern that they are being overprescribed. Allen Frances, who is a Professor and Chair Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry, Duke University, noted that most antidepressants are now off patent and their popularity cannot be attributed to the marketing of pharmaceutical manufacturers. He said general practitioners, not psychiatrists, write most of the prescriptions.

Often they must do so after rushed visits with patients they don’t know very well; who frequently present on one of the worst days of their lives; with nonspecific symptoms of stress, depression, or anxiety. The quickest way to get a worried patient out of the consulting room is to write a prescription.

Research has shown that between one-third and one-half of patients taking antidepressants long-term have no evidence-based reason to be using them. Frances said there are two reasons patients stay on antidepressants who don’t really need them. The first is because of misattribution. Someone who feels better after starting antidepressants will likely assume the pills caused the improvement—not realizing that most mild symptoms are stress-related and are likely to go away on their own. “Stopping pills that never were, or are no longer, necessary is hard to do once the person believes they have worked.”

The second reason people stay on antidepressants long-term is because of the withdrawal symptoms that occur when these medications are stopped too abruptly, after prolonged use and at higher doses. These symptoms can include: lethargy, sadness, anxiety, irritability, trouble concentrating, sleep problems, nightmares, nausea, dizziness, and strange sensations, like brain zaps. They can also continue for a long time. Frances cited a report to the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence, which said:

The available research shows that antidepressant withdrawal reactions are widespread, with incidence rates (i.e. the percentage of antidepressant users experiencing withdrawal) ranging from 27% to 86%, and with nearly half of those experiencing withdrawal describing these reactions as severe. Available research also indicates that withdrawal effects are not ‘self-limiting’ (i.e. typically resolving between 1-2 weeks). Rather, between approx. 25% of users experience AD withdrawal reactions (such as raised anxiety) for at least 3 months after cessation, with many experiencing AD withdrawal for longer than 6 months.

Another Psychology Today article titled, “An Epidemic of Antidepressants,” said the beneficial evidence for antidepressants was ambiguous and there is increasing evidence that their risks have been underestimated. The author suggested the fundamental reason why antidepressants are so widely prescribed is that they fit the ‘medical model’ of mental illness, now the standard view in western culture.

This model sees depression as a medical condition which can be “fixed” in the same way as a physical injury or illness. In a more general way, this fits with our culture’s materialistic assumption that the mind is just a product of the brain, and our mental functioning can be entirely explained in terms of neurological factors.

This is a simplistic and dangerous way of viewing depression, which the overuse of antidepressants shows. Noted by the author, there are many other contributing factors to depression, such as: an unsatisfactory social environment, relationship problems, the frustration of basic needs (for self-esteem, belonging, or self-actualization), a lack of meaning and purpose in life, oppression or unfair treatment, negative or self-critical thinking patterns (related to low self-esteem), a lack of contact with nature, poor diet, and more.

Lack of Evidence for Antidepressants

As it turns out, the evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants seems to have been exaggerated. In 2018 a study published by the University of Oxford reviewed over 500 international trials and found a consistent benefit of antidepressants to placebos. However, the study used the Hamilton Depression Scale on which participants overall score can range from 0 to 52. Antidepressants only reduced the severity of depression an average of less than 2 points, which is not clinically relevant. See “The Lancet Story on Antidepressants, Part 2” for more on this.

A 2008 meta-analysis by Irving Kirsch showed no significant difference between leading antidepressants and placebos. The findings of this study have been reproduced several times, and cannot be easily dismissed. He found that 82% of the response to antidepressants was due to placebo. See “Listening to Antidepressants” and “Dirty Little Secret” for more on Irving Kirsch and his research.

Researchers who analyzed the data for all randomized placebo-controlled depression drug clinical trials submitted to the FDA found that almost half (49%) had no significant improvement over inert placebos. Whether the studies were published and how the results were reported were strongly related to their overall outcomes. Of the 36 studies whose results were negative or questionable, only 3 were published as not positive. Twenty-two were not published and 11 (in the opinion of the researchers) were published as having positive results, when the FDA thought their finding were negative.

The evidence for the benefits of antidepressants is ambiguous, while their risks have been minimized. “It is well known that SSRIs may have some significant side effects, such as fatigue, weight gain, emotional flatness, loss of libido, insomnia, and agitation.” This raises the question of whether the continued use of antidepressants is worth the risks for the vast majority of those who use them.