Priming Young Adults with Vaping

The National Institute of Health announced that recent national survey research discovered that almost 1 in 3 (27.8%) 12th graders reported some kind of use of a vaping device in the past year, while the use of hookahs and regular cigarettes is declining. When asked what they thought was in the mist they inhaled, 51.8% said it was just flavoring, 32.8% said the mist contained nicotine, and 11.1% said they were smoking marijuana or hash oil. Nora Volkow, the director of NIDA, said: “We are especially concerned because the survey shows that some of the teens using these devices are first-time nicotine users.” Recent research suggests some of them could move on to regular cigarette smoking … or other drugs. And some additional research suggests many teens don’t actually know what is in the device they are using.

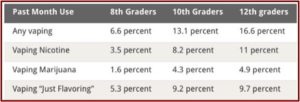

Monitoring the Future (MTF) is a yearly survey of 8th, 10th and 12th graders in school nationwide. The MTF survey is done by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan for NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse. When the survey asked about vaping over the past month, 11% of 12th graders reported vaping nicotine and 4.9% reported vaping marijuana. See the following chart from the NIH news release.

According to the CDC, e-cigarettes are now the most commonly used form of tobacco by youth in the U.S. Dual use, using both regular cigarettes and e-cigarettes, is also common among young adults 18-25. The reasons reported by young people for trying e-cigarettes include curiosity, taste and the belief they are less harmful than other tobacco products. Over 80% of teens and young adults who use e-cigarettes said they use flavored e-cigarettes.

Back in June of 2016 the FDA finalized a rule that extended its regulatory authority to all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, cigars, hookahs and pipe tobacco. The rule requires health warnings and bans free samples. It also restricts youth access to newly regulated tobacco products by not allowing their sale to those younger than 18 and requiring a photo ID. Manufacturers will have up to two years to continue selling their products while they submit a new tobacco product application (and an additional year while the FDA reviews the application).

The rule will help prevent young people from starting to use these products, help consumers better understand the risks of using these products, prohibit false and misleading product claims, and prevent new tobacco products from being marketed unless a manufacturer demonstrates that the products meet the relevant public health standard.

If the new technology in e-cigarettes helps reduce toxicity compared to conventional cigarettes, encourages current smokers to switch completely and/or are not widely used by youth, they potentially could reduce disease and death. “But if any product prompts young people to become addicted to nicotine, reduces a person’s interest in quitting cigarettes, and/or leads to long-term usage with other tobacco products, the public health impact could be negative.” The FDA encouraged manufacturers to explore product innovations that would maximize potential benefits and minimize risks. The revised rule allows the FDA to further evaluate the impact of these products on the health of both users and non-users.

Psychiatric Times reported e-cigarettes were first developed and commercialized in China in 2003. They entered the US market in 2006. During their first ten years on the market, before the FDA ruling discussed above, advertising and sales of e-cigarettes increased exponentially every year. “While tobacco advertising has been banned from television and radio since 1970, e-cigarettes are promoted widely on these media channels, on the web, and in social media, with many ads reaching youth.” Mislabeling has been a problem with some products labeled as nicotine-free containing nicotine and others having higher concentrations of nicotine than labeled.

The evidence for e-cigarettes as a cessation aid to quit regular cigarette smoking is limited. Dual use of regular cigarettes and e-cigarettes is common. One study reported half of current smokers report regular use of e-cigarettes. A meta-analysis of twenty controlled studies found the odds of quitting cigarettes was 28% lower in individuals who used e-cigarettes. However only 2 randomized controlled trials have been done, and: “The quality of evidence was judged to be low grade, and in both trials, e-cigarettes with nicotine were no different in efficacy for quitting smoking than placebo (nicotine-free) e-cigarettes.”

So at this point in time, the evidence does not support the use of e-cigarettes as an aid to stop smoking regular cigarettes. It should be noted that the American Heart Association’s policy statement of e-cigarettes does not recommend their use. However, if a patient has tried and failed other cessation methods or is unwilling to try them, the AHA does recommend trying e-cigarettes for smoking cessation.

There is evidence that smoking e-cigarettes increases the risk of cardio vascular problems. Swedish researchers, in Antoniewicz et al., demonstrated that in healthy volunteers, ten puffs from an e-cigarette caused an increase in endotheial progenitor cells (EPSs) of the same magnitude as smoking one traditional cigarette. The average e-cigarette user takes 230 puffs per day, raising the prospect that prolonged use could result in serious health consequences. “These findings suggest that a very short exposure to ECV [e-cigarette vapor] caused a rapid EPC mobilization in blood, which may indicate an impact on vascular integrity leading to future atherosclerosis [hardening of the arteries].” A heart specialist for the European Society of Cardiology was quoted in the Daily Mail as saying: “It really surprises me that so little vapour from an e-cigarette is needed to start the heart disease ball rolling. It’s worrying that one e-cigarette can trigger such a response.”

Researchers at the University of Connecticut found evidence that e-cigarettes containing a nicotine-based liquid are potentially as harmful as unfiltered cigarettes in causing DNA damage. The study’s lead author said the results surprised him. “I never expected the DNA damage from e-cigarettes to be equal to tobacco cigarettes.” He was shocked the first time he saw the result, so he diluted the samples and ran the controls again. “But the trend was still there – something in the e-cigarettes was definitely causing damage to the DNA.”

Researchers at the University of North Carolina found that not only do e-cigarettes trigger the same immune responses as regular cigarettes, they also trigger some unique reactions. E-cigarette users uniquely showed significant increases with neutrophil-extracellular-trap (NET)-related proteins in their airways. “Left unchecked neutrophils can contribute to inflammatory lung diseases, such as COPD and cystic fibrosis.” The study also found that e-cigarettes produced negative consequences known to occur in regular cigarettes such as an increase of biomarkers of oxidative stress and activation of defense mechanisms associated with lung disease. They also found an over secretion of mucus secretions that have been associated with diseases like chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis and asthma.

Another study by Eric and Denise Kandel, “A Molecular Basis for Nicotine as a Gateway Drug” has raised concerns with e-cigarettes as “pure nicotine-delivery devices.” Their study demonstrated that nicotine acted like a gateway drug for cocaine on the brain of mice, “and this effect is likely to occur whether the exposure is from smoking tobacco, passive tobacco smoke, or e-cigarettes.”

These results provide a biologic basis and a molecular mechanism for the sequence of drug use observed in people. One drug affects the circuitry of the brain in a manner that potentiates the effects of a subsequent drug.Although the typical e-cigarette user has been described as a long-term smoker who is unable to stop smoking, the use of e-cigarettes is increasing exponentially among adolescents and young adults. Our society needs to be concerned about the effect of e-cigarettes on the brain, especially in young people, and the potential for creating a new generation of persons addicted to nicotine. The effects we found in adult mice are likely to be even stronger in adolescent animals. Priming with nicotine has been shown to lead to enhanced cocaine-induced locomotor activity and increased initial self-administration of cocaine among adolescent, but not adult, rats. Whether e-cigarettes will prove to be a gateway to the use of combustible cigarettes and illicit drugs is uncertain, but it is clearly a possibility.

Don’t be too quick to dismiss the Kandels’ nicotine-gateway theory. They were doing basic research on the effects of nicotine on specific areas of the brain. Priming with nicotine enhanced the effects of cocaine in the nucleus accumbens. “Priming with nicotine appeared to increase the rewarding properties of cocaine by further disinhibiting dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area.” They only observed the priming effect of nicotine when mice were given cocaine at the same time as nicotine. For more on Denise Kandel’s gateway hypothesis see: “Rebirth of the Gateway Hypothesis.”