Here’s Some Gray Death

The fact-checking website Snopes looked into a report from Indiana claiming there is a new and dangerous drug called “Gray Death.” The report claimed Gray Death could cause the overdose or death of a drug user if it was accidentally inhaled after it became airborne or if it was absorbed through the skin after contact. Their investigation found the report was true. A local Indiana TV station, WDRB, was the source for the Snopes investigation, saying the Indiana Department of Homeland Security announced Gray Death was found in the Hoosier state beginning in May of 2017. But it seems Indiana was late to the Gray Death party.

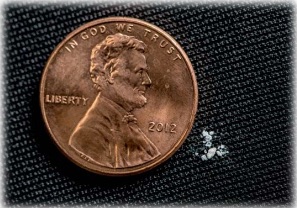

Gray Death is a drug cocktail of heroin, fentanyl, carfentanl, and often U-47700 known on the street as “Pink” or “U4.” Heroin is two to three times as powerful as morphine. Fentanyl is about 50 to 100 times more powerful than heroin. Carfentil is about 100 times more powerful than fentanyl. U4 is the weakest drug in the mix after heroin, at only 7. 5 times the strength of morphine. The drug cocktail looks like concrete mix, thus the nickname of gray death.

Russ Baer of the DEA told NBC News on May 5, 2017 that Gray Death was initially limited to the Gulf Coast and states like Georgia and the mid-West state of Ohio. But it’s also been spotted in places like Chicago, San Diego, and Lexington. A “Pink”-free precursor to Gray Death was spotted in the Atlanta area back in 2012. “We are more routinely seeing deadly cocktails of heroin, fentanyl, various fentanyl-class substances, along with combinations of other controlled substances of varying potencies including cocaine, methamphetamine, and THC. . . . No one should underestimate the deadly nature associated with these cocktails.”

CNN noted that not only do the ingredients of Gray Death vary from sample to sample, some are present in such low concentrations (because of their strength) they may not show up on tests. Donna Ula, director of forensic chemistry at a biochemical company working with state and federal officials to identify unknown street drugs, said “It’s going to constantly vary, and it’s going to keep the chemists and the medical examiners on their toes.” She said Gray Death is “a fast-track route to the morgue.” A forensic chemist with the Georgia Bureau of investigation said even its gray color is a mysterious. “Nothing in and of itself should be that color.”

There have been several overdoses and overdose-related deaths in Georgia and Alabama linked to Gray Death. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation issued a public safety alert on May 4, 2017 about illegal synthetic opioids (Gray Death). The GBI Crime Lab has received about 50 cases of suspected Gray Death this year. Many contain three or four different opioids. One Metro-Atlanta law enforcement agency seized around 8 kilograms of a substance that when field-tested, didn’t identify what the mixture was. Further analysis at the GBI Lab found furanyl fentanyl and U-47700, two of the opioids regularly found in the Georgia Gray Death cocktail.

On May 10, 2017 The Morning Call reported there is Gray Death in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. After making two undercover drug buys at a woman’s home in Bethlehem PA, investigators had the drug packets tested because of their off-white color. They suspected they might contain fentanyl. But the preliminary results showed the packets contained a mixture of heroin, fentanyl and U4—Gray Death. After the preliminary identification, a search warrant was quickly issued: “We wanted to get it off the street as fast as possible.”

The woman’s three children, between the ages of 3 and 9, were living in the home with their mother. Police found some of the drug in a cup sitting on the shelf of a kitchen cabinet” within east reach of the children. The woman was arrested and charged with endangering the welfare of children, drug possession and possession of drug paraphernalia. She was freed after posting $5,000 bail. No word was reported on the children, but they were likely not in their mother’s custody given her charges.

According to Healthline News, the combination of synthetic opioids and/or heroin making up Gray Death varies widely. Given that the drugs or their precursors are created in unregulated labs, domestic drug dealers don’t always know how strong a batch is. “The potency can change from one batch to the next.” Dr. Seonaid Nolan, a clinical scientist in addiction medication at the University of British Columbia said: “Because it’s so potent, a small misstep in the preparation of the drug can lead to lethal consequences.”

This high potency also means it’s more difficult for customs and law enforcement to make searches and seizures, as it allows the drug syndicates to ship less physical product across the border. Sometimes the drugs are even shipped directly through the postal system. “Drug traffickers can move a high quantity or high volume of the product in a fairly small package.”

Traditional opiates like heroin are derived from the poppy plant, meaning the poppy plants have to be grown, harvested and then processed before heroin can be manufactured. “However, synthetic opioids can be produced entirely from chemical precursors.” This makes their production much simpler than heroin, since the entire manufacturing process can be done in a lab.

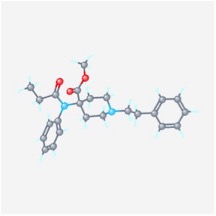

Fentanyl and its analogues have a high lipid solubility, meaning they readily pass through fatty tissues in the body. So fentanyl is used in transdermal patches and even lollipops, allowing it to enter the blood stream without having to be digested in the stomach. Since it doesn’t get metabolized, you need smaller amounts of fentanyl because it can go directly to the brain through the blood system. This also explains its danger if it becomes airborne or comes in contact with exposed skin. Edward Bilsky, a professor of Biomedical Sciences at Pacific Northwest University said:

[These drugs] are very fast acting and produce profound depression of respiration and other central nervous system functions leading to many deaths. . . . First responders and others around the victim need to be careful due to secondary exposure.

According to the DEA, fentanyl analogs, like acetyl fentanyl and furanyl fentanyl are manufactured in China by clandestine labs, and then smuggled into the U.S. through established drug smuggling routes in Mexico. Mexican drug traffickers also manufacture their own analogs of fentanyl. In the past, the Chinese government denied they were the source of illicit fentanyl being smuggled into the U.S. But DEA officials and others met with Chinese officials in 2016, which prompted China to regulate four fentanyl-related substances in an effort to help stem the flow of these opioids into the U.S. in action that went into effect in March of 2017.

Carfentanil was one of these substances. Because of its off-the-charts strength, it was receiving a lot of press coverage in 2016. See “Fentanyl: Fraud and Fatality” and “The Devil in Ohio.” But unless you followed news on the death of Prince, you may not have heard of “Pink” (U-47700 or U4) before. In addition to fentanyl and Percocet (oxycodone-acetaminophen), Pink was found in his system. In November of 2016, the DEA temporarily classified U-47700 as a Schedule I controlled substance, due to its “immanent threat to public health and safety.” The DEA received at least 46 confirmed reports of deaths associated with U-47700—31 in the state of New York and 10 in North Carolina. “This scheduling action will last for 24 months, with a possible 12-month extension if DEA needs more data to determine whether it should be permanently scheduled.”

In addition to Georgia, Pennsylvania and Ohio, drug busts in multiple states are reporting they have seized quantities of Grey Death. Traffic stops in Greenville County South Carolina found 17 pounds of heroin and one pound of Grey Death. There have been two reported seizures of Grey Death in Virginia. Grey Death has been reported in Florida since November of 2016. It’s been found in Alabama. In a video from WCPO in Cincinnati, Ohio, Detective Jim Larkin of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Department wondered why anyone would try something called Grey Death. “Here’s some Grey Death. Now what do think is going to happen to you? Why do you think it’s called Grey Death?”