Worse Results with Psych Meds

Psych meds are popular. One in six U.S. adults (16.7% of 242 million) reported filing at least one prescription for a psychiatric medication in 2013. That increased with adults between the ages of 60 and 85, where one in four (25.1%) reported using psych meds. Only 9% of adults between the ages of 18 and 39 reported using one or more psych drugs. Most psychiatric drug use was long-term, meaning patients reported taking these meds for two years or more; 82.9% reported filling 3 or more prescriptions in 2013. “Moreover, use may have been underestimated because prescriptions were self-reported, and our estimates of long-term use were limited to a single year.”

The above findings were reported in a research letter written by Thomas Moore and Donald Mattison in JAMA Internal Medicine. Their findings got a fair amount of media attention, including articles in Live Science (here), The New York Times (here), Mad in America (here), Psychology Today (here) and even Medscape (here).

Moore said the biggest surprise was that 84.3% of all adults using psychiatric medication (34.1 million) reported using these meds long-term, meaning over two years. He said the high rates of long-term use of psych meds raises the need for closer monitoring and a greater awareness of the potential risks.

Both patients and physicians need to periodically reevaluate the continued need for psychiatric drugs. . . This is a safety concern, because 8 of the 10 most widely used drugs have warnings about withdrawal/rebound symptoms, are DEA Schedule IV, or both.

The ten most commonly used psychiatric drugs in ranked order were:

- Sertraline (Zoloft, an SSRI antidepressant)

- Citalopram (Celexa, an SSRI antidepressant)

- Alprazolam (Xanax, a benzodiazepine for anxiety)

- Zolpidem tartrate (Ambien, a hypnotic prescribed for sleep)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, an SSRI antidepressant)

- Trazodone (an antidepressant often prescribed for sleep)

- Clonazepam (Klonopin, a benzodiazepine for anxiety)

- Lorazepam (Ativan, a benzodiazepine for anxiety)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro, an SSRI antidepressant)

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta, an SNRI antidepressant)

Drawing on data from a different source in “Drugs on the Mind” for Psychology Today, Hara Estroff Marano said the Institute for Healthcare Informatics (IMS) reported there were 4.4 billion prescriptions dispensed in 2015, with total spending on medicines reaching $310 billion. “Over a million of the prescriptions written for a psychiatric drug were to children 5 years of age or younger.” There were 78.7 million people in the U.S. using psychiatric meds. Within this group, 41.2 million were prescribed one or more antidepressants; 36.6 million were given anti-anxiety medications; and 6.8 million were given antipsychotics.

These figures were different than the percentages reported above from the Moore and Mattison study. Moore and Mattison found that 12% (29 million) reported using antidepressants; 8.3% (20 million) reported using anxiolytics and 1.6% (3.9 million) reported using antipsychotics. Their 1 in 6 (16.7%) figure would then be 40.4 million people using at least one psychiatric medication. Regardless of which data source you use, there are millions of U.S. citizens taking at least one psychiatric drug and therefore at risk of experiencing the adverse effects associated with these drug classes.

Anatomy of an Epidemic by Robert Whitaker described how psychiatric drugs seem to be contributing to the rise of disabling mental illness rather than treating those who suffer from it. What follows is a sampling of comments from Anatomy that he made about benzodiazepines (anxiolytics), which are widely used to treat anxiety and insomnia. Whitaker said long-term benzodiazepine use can worsen the very symptoms they are supposed to treat. He cited a French study where 75 percent of long-term benzodiazepine users “. . . had significant symptomatology, in particular major depressive episodes and generalized anxiety disorder, often with marked severity and disability.”

In addition to causing emotional distress, long-term benzodiazepines usage also leads to cognitive impairment (137). Although it was thirty years ago that governmental review panels in the United States and the United Kingdom concluded that the benzodiazepines shouldn’t be prescribed long-term … the prescribing of benzodiazepines for continual use goes on (147).

In her article for Medscape, Nancy Melville pointed out the CDC found zolpidem (a so-called “Z” drug) was the number one psychiatric linked to emergency department visits. As many as 68% of patients used it long-term, while the drug is only recommended for short-term use. Up to 22% of zolpidem users were also sustained users of opioids.

Among the concerns with antidepressants are that they are not more effective than placebos (see discussions of the research of Irving Kirsch, starting here: “Do No Harm with Antidepressants”). In some cases they contribute to suicidality and violence (see “Psych Drugs and Violence” and “Iatrogenic Gun Violence”) and they have a risk of withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation.

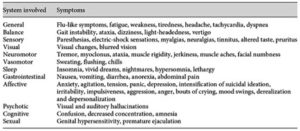

In a systematic review of the literature, Fava et al. concluded that withdrawal symptoms might occur with any SSRI. The duration of treatment could be as short as 2 months. The prevalence of withdrawal was varied; and there was a wide range of symptoms, encompassing both physical and psychological symptoms. The table below, taken from the Fava et al. article, noted various signs and symptoms of SSRI withdrawal.

The withdrawal syndrome will typically appears within a few days of drug discontinuation and last for a few weeks. Yet persistence disturbances as long as a year after discontinuation have been reported. “Such disturbances appear to be quite common on patients’ websites but await adequate exploration in clinical studies.”

Clinicians are familiar with the withdrawal phenomena that may occur from alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, opioids, and stimulants. The results of this review indicate that they need to add SSRI to the list of drugs potentially inducing withdrawal phenomena. The term ‘discontinuation syndrome’ minimizes the vulnerabilities induced by SSRI and should be replaced by ‘withdrawal syndrome’.

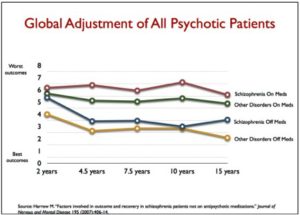

Updating his critique of the long-term use of antipsychotics in Anatomy of an Epidemic, Robert Whitaker made his finding available in a paper, “The Case Against Antipsychotics.” There are links to both a slide presentation and a video presentation of the information included in his paper. The breadth of material covered was difficult to summarize or select out some of the more important findings. Instead, we will look at what Whitaker said was the best long-term prospective study of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders done in the U.S. The Harrow study assessed how well an original group of 200 patients were doing at various time intervals from 2 years up until 20 years after their initial hospitalization for schizophrenia. In his paper, Whitaker reviewed the outcome for these patients after 15 and 20 years of follow up.

Harrow discovered that patients not taking medication regularly recovered from their psychotic symptoms over time. Once this occured, “they had very low relapse rates.” Concurrently, patients who remained on medication, regularly remained psychotic—even those who did recover relapsed often. “Harrow’s results provide a clear picture of how antipsychotics worsen psychotic symptoms over the long term.” Medicated patients did worse on every domain that was measured. They were more likely to be anxious; they had worse cognitive functioning; they were less likely to be working; and they had worse global outcomes.

There is one other comparison that can be made. Throughout the study, there were, in essence, four major groups in Harrow’s study: schizophrenia on and off meds, and those with milder psychotic disorders on and off meds. Here is how their outcomes stacked up:

As Whitaker himself noted, his findings have been criticized from several individuals. However, he answered those critiques and demonstrated how they don’t really hold up. Read his paper for more information. But his conclusions about the use of antipsychotic medications are not unique. In the article abstract, for “Should Psychiatrists be More Cautious About the Long-Term Prophylactic Use of Antipsychotics?” Murray et al. said:

As Whitaker himself noted, his findings have been criticized from several individuals. However, he answered those critiques and demonstrated how they don’t really hold up. Read his paper for more information. But his conclusions about the use of antipsychotic medications are not unique. In the article abstract, for “Should Psychiatrists be More Cautious About the Long-Term Prophylactic Use of Antipsychotics?” Murray et al. said:

Patients who recover from an acute episode of psychosis are frequently prescribed prophylactic antipsychotics for many years, especially if they are diagnosed as having schizophrenia. However, there is a dearth of evidence concerning the long-term effectiveness of this practice, and growing concern over the cumulative effects of antipsychotics on physical health and brain structure. Although controversy remains concerning some of the data, the wise psychiatrist should regularly review the benefit to each patient of continuing prophylactic antipsychotics against the risk of side-effects and loss of effectiveness through the development of supersensitivity of the dopamine D2 receptor. Psychiatrists should work with their patients to slowly reduce the antipsychotic to the lowest dose that prevents the return of distressing symptoms. Up to 40% of those whose psychosis remits after a first episode should be able to achieve a good outcome in the long term either with no antipsychotic medication or with a very low dose.

All three classes of psychiatric medications reviewed here have serious adverse effects that occur with long-term use. In many cases, they lead to a worsening of the very symptoms they were supposed to “treat.” Increasingly, it is being shown that the psychiatric drug treatments are often worse than the “mental illness” they allegedly treat.