Rooting for the Underdog

In July of 2010, a 57-year-old partner at the law firm Reed Smith jumped in front of a subway train in Chicago and died. His widow, Wendy Dolin, sued the pharmaceutical companies GlaxoSmithKline (who originally manufactured Paxil) and Mylan (the drug company who manufactured paroxetine, the generic version that Stewart Dolin took), charging that the drug caused akathisia, which led to his suicide. GSK attorneys dismissed the testimony of the plaintiff’s expert witness as “junk science,” which argued for a link between the drug and suicide. However it seems the jury disagreed, since on April 20th, 2017 they awarded a $3 million verdict for the plaintiff.

Mylan was released from the suit by the trial judge, who ruled they had no control over the drug’s label. GSK continues to maintain the company wasn’t responsible since it hadn’t manufactured the drug taken by Dolin. A Chicago Tribune article quoted Wendy Dolin as saying the ruling was “a great day for consumers.” The trial was not just about the money for her. It was about awareness to a health issue. But this isn’t the end. “Officials from the pharmaceutical company said the verdict was disappointing and that they plan to appeal.” GSK continues to assert they weren’t responsible because they didn’t manufacture the drug taken by Dolin.

Writing for Mad in America, attorney and activist Jim Gottstein noted the legal significance of the case, as it established GSK did not inform the FDA or doctors that Paxil could cause people to commit suicide—a conclusion GSK continues to deny. A second legal hurdle overcome by the ruling is a Catch-22 dilemma since SSRIs, like Paxil, are now usually prescribed as generics. “The generic drug manufacturer [Mylan} isn’t liable because it was prohibited from giving any additional information and the original manufacturer [GSK] isn’t liable because it didn’t sell the drug.” You can read Jim Gottstein’s article for an explanation of how these legal hurdles were overcome.

Bob Fiddaman interviewed Wendy Dolin after the verdict and she described some disturbing tactics used by GSK attorneys. She said depositions that should have been a few hours long became eight hours, “in an attempt to wear people down.” She said GSK asked the same question over and over again, hoping to confuse or manipulate people. She alleged they also called her friends, trying to get them to say something negative about her relationship with her deceased husband.

As a therapist, as a mother and a compassionate human being, I am aware there was no purpose to have done such. I have talked to therapists, physicians and pharmaceutical lawyers and all agree there was nothing gained by this other than to show me that GSK would stop at nothing to intimidate me.

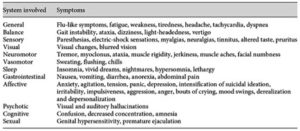

During the trial it came to light that 22 individuals had died in Paxil clinical trials, 20 by suicide; two other deaths were suspected to be suicide. “All 22 victims were taking Paxil at the time, and 80% of these patients were over the age of 30.” GSK tried to argue their “illness” caused their deaths and not Paxil. Wendy Dolin said the lawsuit showed that “akathisia is a real, legitimate adverse drug reaction.” The public needs to be aware of its signs and symptoms.

Wendy said she knew even before they went to trial, that GSK would appeal the ruling if they lost. She thought there was a GSK lawyer in the courtroom during the trial gathering information for the appeal process. She said it had been suggested this case could go all the way to the Supreme Court, because GSK is afraid of the legal ramifications of a guilty verdict. The process could take 5-7 years. She said: “Clearly this case has never been about money. For me, it has always been about awareness, highlighting akathisia and ultimately changing the black box warning to include all ages.”

Writing for STAT News, Ed Silverman suggested the new head of the FDA, Scott Gottlieb, should require a stronger warning label for Paxil. “For the past decade, Paxil’s label has not carried any information indicating the drug poses a statistically significant risk of suicidal behavior for anyone over 25.” Yet there is scientific evidence of such a risk. See Table 16 in the linked “Exhibit 40” document of his article (I assume it’s from the Dolin trial). Silverman said: “For public health reasons, the FDA should pursue a warning.” A former FDA commissioner was quoted as saying it was hard for him to understand why the warning of increased suicidal risk was not in the label.

But sucidality is not just a risk with Paxil (paroxetine). A meta-analysis done by Peter Gotzsche of the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that antidepressants doubled the risk of suicidality and aggression in children and adolescents. Gotzsche and his team of researchers reviewed the clinical study reports for duloxetine (Cymbalta), fluoxetine (Prozac and Sarafem), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), and venlafaxine (Effexor). Estimates of harm could not be accurately done because the quality of the clinical study reports varied drastically, limiting their ability to detect the harms. The true risk for serious harms was uncertain, they said, as the low incidence of these events and the poor design and reporting of the trials made it difficult to get accurate estimates.

A main limitation of our review was that the quality of the clinical study reports differed vastly and ranged from summary reports to full reports with appendices, which limited our ability to detect the harms. Our study also showed that the standard risk of bias assessment tool was insufficient when harms from antidepressants were being assessed in clinical study reports. Most of the trials excluded patients with suicidal risk and so our numbers of suicidality might be underestimates compared with what we would expect in clinical practice.

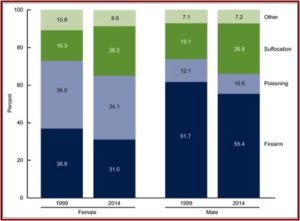

In April of 2016, the CDC released data indicating the suicide rate in the U.S. increased by 24% from 1999 to 2014. Overall, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased from 10.5 per 100,000 in 1999, to 13.0 per 100,000 in 2014. The rates increased for both males and females and for all ages from 10 to 74. The age-adjusted rates for males (20.7 per 100,000 population), was over three times that of females (5.8 per 100,000). Males preferred firearms as a method (55.4%), while poisoning was the most frequent method for females (34.1%). However, this was a lower percentage for both sexes than in 1999. See the following figure from the CDC Report noting suicide deaths by method and sex for 1999 and 2014.

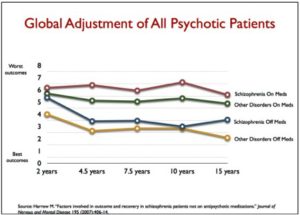

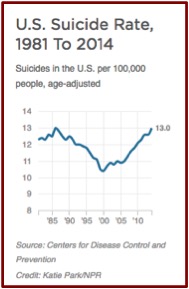

This reverses a trend from 1985 to 2000, where the U.S. suicide rate was dropping. See the following chart taken from an NPR report on the same data. The president-elect of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), Maria Oquendo, said she thought the late 1980s drop was probably due to the fact that new antidepressants (SSRIs) were more effective and had fewer side effects.

This reverses a trend from 1985 to 2000, where the U.S. suicide rate was dropping. See the following chart taken from an NPR report on the same data. The president-elect of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), Maria Oquendo, said she thought the late 1980s drop was probably due to the fact that new antidepressants (SSRIs) were more effective and had fewer side effects.

Karter noted how Oquendo and Christine Moutier (from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention) both saw the addition of black box warnings of the potential for suicide in teenagers and young adults as contributing the rise in suicide rates. Moutier was more direct, stating the progress in depression treatment in the 80s and the 90s “was undone in recent years because of concerns that antidepressants could increase suicide risk.” Oquendo thought the increase of suicide deaths in younger populations was potentially due to the understandable reluctance of physicians to prescribe antidepressants to these individuals, “even when they’re aware the individual is suffering from depression.” She added how research showed the benefits outweigh the risks of prescribing antidepressants to children and adolescents.

But Justin Karter indicated this suggestion, that the warning labels led to a decreased number of antidepressant prescriptions for teenagers and adults, was inaccurate. Although several media outlets reported the increase in the suicide rate, they didn’t report the corresponding increase of Americans taking antidepressants, a rate that has nearly doubled.

But Justin Karter indicated this suggestion, that the warning labels led to a decreased number of antidepressant prescriptions for teenagers and adults, was inaccurate. Although several media outlets reported the increase in the suicide rate, they didn’t report the corresponding increase of Americans taking antidepressants, a rate that has nearly doubled.

There was a report published in the British Medical Journal in June of 2014 that indicated black box warnings on SSRIs had a paradoxical effect, with an increase in suicide attempts among youths. Mad in America cited 12 critics of the study and noted its multiple flaws. The unwarranted conclusion, namely lead to increasing the prescription of antidepressants to teenagers and youths, had the potential to do considerable harm. Mad in America concluded that it should never have been published. Among the problems with the study were the following:

The researchers’ stated conclusion, which was that a decrease in antidepressant prescribing in youth following the black box warning led to an increase in suicide attempts, isn’t supported by their own data. (1) There was not a significant decrease in SSRI prescriptions to teenagers and young adults following the black box warning. (2) Psychotropic drug poisonings are not a good proxy for suicide attempts. (3) This coding category actually tells of poisonings due to the use of psychiatric drugs, as opposed to their non-use. (4) Finally, there was no significant increase in the number of poisonings.

Additionally, Kantor et al., in “Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the US” reported data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated that the use of antidepressants increased from 6.8% to 13% between 1999 and 2012. Yet, as Justin Karter reported, “The American Psychiatric Association guidelines continue to suggest medications as the preferred treatment for moderate to severe depression.”

If you’re still not convinced, take some time to read through a series of scientific articles submitted by Peter Breggin in his affidavit for another Paxil-related suicide trial. The topics covered included exhibits of Paxil causing suicidal behavior as well as SSRIs and SSRI withdrawal causing suicidality. There is another section on Dr. Breggin’s website that is an “Antidepressant Drug Resource & Information Center” with even more relevant articles.

Given the above discussion on antidepressants, the recent court ruling in Illinois awarding $3 million to Wendy Dolin has the potential to lead to an unknown number of future lawsuits, if it is upheld upon appeal. This could end up costing the pharmaceutical companies that brought now off patent SSRIs and SNRIs to market untold millions and possibly billions of dollars in further awards. So you can bet that GlaxoSmithKline has plenty of pharma companies (and their legal representatives) rooting for GSK to overturn the ruling in the Dolin case. Me, I’m rooting for the underdog here—the 13% of Americans who are taking antidepressant medications without clearly knowing the potential they have to make their depression and its consequences worse.