Drugs Do Not Fix Chemical Imbalances

Researchers at Harvard’s McLean Hospital observed that the public perception of mental illness was increasingly understood in neurobiological and genetic terms. There is some evidence that these explanations had an unintended consequence of reducing optimism for recovery among individuals with depression. Despite this, very little is known about how these beliefs interact with the treatment process and outcomes in a psychiatric treatment setting. They wanted to know if the language used affected treatment protocols and patient expectations. They found that believing depression was caused by a chemical imbalance was related to poorer treatment expectations.

In fact, they found that more depressed individuals showed a stronger relationship between chemical imbalance beliefs and lower treatment expectations. In “The dangers of the chemical imbalance theory of depression,” Derek Beres noted while the chemical marker serotonin is correlated with depression, it does not cause depression. “Decade after decade, however, we’ve been marketed the idea that chemical imbalance is the culprit behind depression.”

Instead of doctors diagnosing patients, they increasingly confirm what the patient suspected all along. The patients self-diagnose because they saw an advertisement or listened to a friend. Doctors too often comply without further investigating of the reasons for their reported distress. Medicalizing mental health softens the stigma of depression, but it also disempowers the patient. In “Stressors and chemical imbalances: Beliefs about the causes of depression in an acute psychiatric treatment sample,” the McLean researchers wrote:

More recent studies indicate that participants who are told that their depression is caused by a chemical imbalance or genetic abnormality expect to have depression for a longer period, report more depressive symptoms, and feel they have less control over their negative emotions.

Doctors, media, and advertising come together with a similar message. Everyday blues is a real medical condition, everyone is susceptible to clinical depression, and drugs correct the underlying physical conditions. Counseling aimed at self-insight seems to serve little purpose. The McLean team of researchers found patients expected little from psychotherapy and a great deal from pills. “When depression is treated as the result of an internal and immutable essence instead of environmental conditions, behavioral changes are not expected to make much difference.”

Doctor Ronald Pies referred to and cited “Stressors and chemical imbalances” in his January article in Psychiatric Times, “What We Tell Patients about Depression, and What They Say They Have Been Told.” Pies said the study found that the most commonly endorsed explanations for depression were psychosocial explanations, not “the chemical imbalance notion.” He said popular beliefs about the cause of depression could be adopted from a variety of sources, including television advertisements and anti-stigma campaigns promoting biogenetic explanations. These beliefs could also come from individual treatment experience. “All of this is simply to note that popularization of the chemical imbalance canard is almost certainly an over-determined effect, in which the role of psychiatrists (or other clinicians) is but 1 possible causal factor.”

But he seems to have glossed over the primary finding of “Stressors and chemical imbalances.” Patients who believe a chemical imbalance or genetic abnormality caused their depression do worse. The results of the study’s abstract said:

We found that although psychosocial explanations of depression were most popular, biogenetic beliefs, particularly the belief that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance, were prevalent in this sample. Further, the chemical imbalance belief related to poorer treatment expectations. This relationship was moderated by symptoms of depression, with more depressed individuals showing a stronger relationship between chemical imbalance beliefs and lower treatment expectations. Finally, the chemical imbalance belief predicted more depressive symptoms after the treatment program ended for a 2-week measure of depression (but not for a 24-hour measure of depression), controlling for psychiatric symptoms at admission, inpatient hospitalizations, and treatment expectations.

“Stressors and chemical imbalances” was not critiquing psychiatry for spreading the chemical imbalance theory, which Pies has called a kind of urban legend. The researchers examined etiological beliefs about depression and studied how they were related to treatment expectations and outcomes. If you believed in the chemical imbalance theory of depression, you tended to have poorer treatment outcomes. But that isn’t the only problem with believing in this “urban legend.”

Consequences of Believing in a Chemical Imbalance

Dutch researchers interviewed people who were given medical advice to discontinue antidepressants. The participants’ use of antidepressants was determined to be “not indicated” based upon clinical practice guidelines. This meant that participants had no current mental health diagnoses, no history of recurring mental health problems, and they had been taking antidepressants longer than nine months. Reporting on the study for Mad in America, Peter Simons said that despite receiving advice to discontinue, more than half refused to stop taking their antidepressant. The researchers identified two significant barriers to discontinuation.

The first was fear that if they ever stopped taking antidepressants, they would not be able to cope with the rebound depression. One of the participants said: “That’s my biggest fear. The misery I was in, before I got these medicines. I never want to relive that. I never want to go back to how I felt then. And because of this fear, I just can’t attempt to stop them.” Another person said if she would remain well, she would quit tomorrow. “But . . . to go through the hell I went through again? No.”

The second barrier was a belief in the serotonin deficiency theory, the chemical imbalance theory. The participants described their antidepressant use as supplying a deficient substance they needed to function normally. This resulted in their acceptance of a lifelong dependency. “I just need it. For me, this isn’t a psychological illness, it’s physical. And my body isn’t able to make enough serotonin, so I take the pill to supply it.”

There was a comparison to diabetes by her doctor reported by one participant.

She (the GP) told me, you should see it like you have a deficiency in your brain, you miss a certain substance and the medicine supplies it. She told me it’s just like someone with diabetes who needs insulin for the rest of their life. Well, I kind of believe that, so never questioned my use since.

The Dutch researchers said the biological model for depression seemed to backfire:

Another important barrier was the notion that antidepressants are necessary to supply the deficient serotonin. This serotonin deficiency resulted in patients expecting continued use of their medication. Presumably this is the result of the explanation the GPs gave to their patients at first prescription, or at least what patients (choose to) remember. The biological model for depression seems to backfire, making it difficult to persuade the patient to discontinue the drug. This is an important and new finding. GPs must keep this in mind while explaining the course of treatment for depressive and anxiety disorders. On the other hand, uneasiness with the perception of a biological cause could enhance attempts to stop antidepressants.

The chemical imbalance theory of depression is a false, unfounded report. For decades, the idea has been falsely marketed to consumers that a chemical imbalance is the culprit behind depression. Even psychiatrists, as seen with Dr. Pies, want to distance themselves from this “canard.” This urban legend is associated with poorer treatment outcomes and leads individuals with no apparent clinical need to remain on antidepressants instead of tapering off of them. We need to ask, how did we get here?

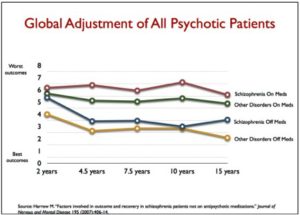

In his interview for Scientific American, “Has the Drug-Based Approach to Mental Illness Failed?”, Robert Whitaker described his journey away from the conventional understanding that depression and schizophrenia were caused by chemical imbalances in the brain, to founding the webzine, Mad in America.

Whitaker said he is convinced that psychiatric medications cause net harm when used over the long term. “I wish that weren’t the case, but the evidence just keeps mounting that these drugs, on the whole, worsen long-term outcomes.” Increasingly, he is not sure the medications provide real a short-term benefit either. “When you look at the short-term studies of antidepressants and antipsychotics, the evidence of efficacy in reducing symptoms compared to placebo is really pretty marginal, and fails to rise to the level of a ‘clinically meaningful’ benefit.” His concern and the concern of Mad in America has grown beyond studies with psychiatric medications:

Mad in America’s mission is to serve as a catalyst for rethinking psychiatric care in the United States (and abroad). We believe that the current drug-based paradigm of care has failed our society, and that scientific research, as well as the lived experience of those who have been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, calls for profound change.

He thinks our society organized itself with regard to mental illness around a false narrative presented as a narrative of science. In the early 1980s, we began to hear that psychiatric disorders were cause by chemical imbalances in the brain; and that like insulin did for diabetes, there was a new generation of psychiatric medications that could fix those imbalances. “We came to believe that there was a sharp line between the ‘normal’ brain and the ‘abnormal’ brain, and that it was medically helpful to screen for these illnesses, and that psychiatric drugs were very safe and effective, and often needed to be taken for life.”

But what can be seen clearly today is that this narrative was a marketing story, not a scientific one. It was a story that psychiatry, as an institution, promoted for guild purposes, and it was a story that pharmaceutical companies promoted for commercial reasons. Science actually tells a very different story: the biology of psychiatric disorders remains unknown; the disorders in the DSM have not been validated as discrete illnesses; the drugs do not fix chemical imbalances but rather perturb normal neurotransmitter functions; and even their short-term efficacy is marginal at best.

The above quotes from participants in the Dutch study and the quote on how the biological model for depression backfired, are found in the research article published in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, “Patients’ attitudes to discontinuing not-indicated long-term antidepressant use.”