The Sackler Cartel Goes Before the Supreme Court

The Sackler family’s legal maneuverings to avoid financial consequences from their privately-owned company, Purdue Pharma, just had another development. In August of 2023 the U.S. Supreme Court temporarily blocked the bankruptcy deal for Purdue Pharma that would have shielded members of the Sackler family from additional lawsuits and cap the Sacklers’ personal liability at $6 billion. This was in response to a Justice Department objection that said the settlement would allow the Sackler family to take advantage of legal protections meant for debtors in financial distress, while the Sackler family is reportedly worth $11 billion. The New York Times and SCOTUSblog reported on the Supreme Court arguments on Monday, December 4th over the bankruptcy deal.

The case could have far-reaching implications for similar lawsuits. If the court approves the deal, it would affirm a litigation tactic that has become popular in resolving lawsuits where people claim similar injuries from the same entity, whether that is a drug or a consumer product. “By turning to the bankruptcy courts as a tool to resolve those claims, businesses aim to free themselves from civil liability and prevent future lawsuits.” If the Supreme Court were to block the use of such a mechanism in this case, the Sackler family would no longer be shielded from civil lawsuits. Additionally, the Purdue Pharma bankruptcy settlement deal would be in jeopardy as the Sackler family previously threatened to walk away from the settlement if the bankruptcy protections were not included in the agreement. See “Carrot-and Stick Tactics of Purdue and the Sacklers” and “Supreme Court considers $6bn deal that shields Sacklers.”

The NYT said it was rare for the Supreme Court to hear a bankruptcy dispute, but this one was precipitated when a watchdog office of the Justice Department, the U.S. Trustee Program, petitioned the court to review the deal. Additionally, the opioid crisis is a nationally important issue. Allowing third parties to be shielded without declaring bankruptcy themselves has become an increasingly popular tactic for avoiding liability. And these rulings have divided lower courts. The objection by the U.S. Trustee Program was, if approved, the Sacklers would get the benefits of bankruptcy without its costs.

Individuals who may want to sue individual Sackler family members—the ones actively involved in decisions made by Purdue Pharma—in civil court would be prevented from doing so. “The U.S. trustee argued that their constitutional due process rights would be summarily extinguished.” While the Justice Department and a few other plaintiffs are challenging the settlement, most others are concerned about the potential loss of funds to initiatives intended to address the opioid crisis.

Under the deal, Purdue would pay $1.2 billion toward the settlement immediately upon emerging from bankruptcy, with millions more expected in the years to come. The Sacklers would pay up to $6 billion over 18 years, with almost $4.5 billion due in the first nine years.

According to an agreement with tribal plaintiffs, all 574 federally recognized Native American tribes are eligible for payouts from a trust worth about $161 million.

Each state has devised a formula with its local governments for distributing the Purdue money. But all must follow the guidance for using it: that it be largely applied to initiatives intended to ease the opioid crisis, including addiction treatment and prevention.

If the agreement is upheld, about 138,000 plaintiffs, individuals and family members of victims who died from overdoses, would be able to file claims to a trust that would hold $700 to $750 million. Payments are expected to range from $3,500 to $48,000. “Though the payouts are small, the Purdue plan is one of only very few opioid settlements across the nation that set aside money for individuals.”

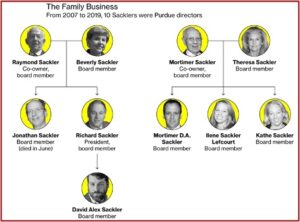

Purdue Pharma would cease to exist. A new company, Knoa Pharma, would receive the assets from Purdue. Knoa would be owned by creditors, and would manufacture addiction treatment and opioid reversal medicines at no profit. See “The Bondage of Buprenorphine” for a potential new product already developed by a Sackler. Knoa would continue to make opioids like OxyContin as well as nonopioid drugs, with the profits going towards the settlement funds. The Sacklers have been off the Purdue board since 2018, so why it there such resistance to members of the Sackler family avoiding further financial liability?

CNN reported members of the Sackler family withdrew more than $10 billion from Purdue Pharma and placed the money in family trusts and holding companies as pressure built over the nation’s opioid epidemic. An audit of Purdue related to its filing for bankruptcy in September 2020 showed that from 2008 to 2018 the family withdrew more than eight times as much money from the company as the previous 13 years. “From 1995 through 2007, the Sacklers received $1.3 billion from Purdue; but from 2008 through 2018, those payments amounted to $10.7 billion.” The larger withdrawals came after Purdue’s 2007 plea deal with the Justice Department to pay a $600 million penalty on a felony charge of misleading and defrauding physicians and consumers over OxyContin.

The withdrawals came during a time when Purdue Pharma was accused of fueling the nation’s opioid epidemic and amid growing concerns from many states that a significant amount of the family’s wealth may be held overseas; therefore unavailable to plaintiffs seeking relief through the courts.

According to StatNews, political appointees at the Justice Department refused to approve felony charges for Purdue executives, letting the company off with a $600 million fine. Richard Sackler admitted he never bothered to read the entire 2007 plea deal document where prosecutors gave guidelines for Purdue’s future behavior. Instead, they doubled down on marketing OxyContin. The important result of the ruling was there was no trial. “A trial would have exposed the company’s OxyContin profits to forfeiture or prompted one of the executives to expose the magnitude of OxyContin scion Richard Sackler’s participation in the admitted crimes.”

An attorney for the Raymond Sackler family said the amount the family withdrew was publicly known. ““These distribution numbers were known at the time the proposed settlement was agreed to by two dozen attorneys general and thousands of local governments.” But Letitia James, the New York Attorney General said the audit showed the need for even more information:

The fact that the Sackler family removed more than $10 billion when Purdue’s OxyContin was directly causing countless addictions, hundreds of thousands of deaths, and tearing apart millions of families is further reason that we must see detailed financial records showing how much the Sacklers profited from the nation’s deadly opioid epidemic.

CNN said a spokesperson for the Sackler family defended the withdrawals, saying: “Members of the Sackler family who served on Purdue’s board of directors acted ethically and lawfully, and the upcoming release of company documents will prove that fact in detail.” The statement of the Purdue audit said the family’s ownership interest of Purdue Pharma had been valued at between $10 billion to $12 billion.

In his testimony for federal bankruptcy court, Dr. Richard Sackler, a former president and co-chairman of the bord of directors of Purdue Pharma said he, the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma did not have any responsibility for the opioid crisis in the United States. Yet during his tenure, Purdue pleaded guilty twice to federal criminal charges related to marketing and sales of OxyContin. In an email he wrote in 2001, he said “We have to hammer on abusers in every way possible… They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

A congressional committee investigating the Sacklers, released a statement saying the Sackler family, who owned a controlling interest in Purdue Pharma since 1952, were collectively worth $11 billion. See the statement for a listing of the Sackler family’s assets. The chairperson of the committee said the family built its enormous fortune in large part through sales of OxyContin:

Members of the Sackler family pushed Purdue to use deceptive marketing practices to flood communities with this dangerous painkiller, and now the Sackler family is attempting to use Purdue’s bankruptcy proceedings to evade individual responsibility for their role in fueling the opioid epidemic.

Untangling the contributions of the Sackler family from executives for Purdue Pharma in order to get a clear picture of exactly what individual family members were responsible for may be an impossible task. But looking at how family members contributed to the opioid epidemic and Purdue Pharma’s facilitation of the opioid epidemic is easily done.

Arthur Sackler’s marketing strategies were applied to OxyContin after his death, and Mortimer Sackler transferred millions of dollars from trust companies to himself as early as 2009. Records show approximately $1 billion in wire transfers between the Sacklers, entities they control, and different financial institutions—including funds placed in Swiss bank accounts.

According to StatNews, the evidence of callous greed by Purdue was chilling. The privately-held company fired employees who tried to blow the whistle on its activities and maneuvered to have reporters working on the story of fraud at Purdue fired or removed from their beats. Sales reps were encouraged to allow doctors to believe morphine was stronger than OxyContin; it wasn’t. Executives at Purdue knew the opposite was true.

The 2007 plea deal document discussed above didn’t slow them down. It allowed Purdue Pharma to continue marketing and selling OxyContin. Now with the assistance of consultants at McKinsey & Co., they “turbocharged” their sales, concentrating on known pill mill operators, pushing the highest-dosage pills, “and banning together with other opioid makers to pull end-runs around FDA regulators.”

For more information on the Sacklers and OxyContin, read Pain Killer, by Barry Meier, which “exposes the roots of the opioid epidemic at the hands of Purdue Pharma and Raymond and Mortimer Sackler.” Also see: “What Purdue and the Sackler Family Treasure,” “It’s Strictly Business,” and “Giving an Opioid Devil Its Due.” Read “The Tale of the OxyContin Lie” and watch PainKiller on Netflix if you think the Sackler family should get a pass by the Supreme Court.