If TD Walks Like a Duck …

On April 10, 2020, Psychiatric Times published “Advances in Tardive Dyskinesia: A Review of Recent Literature.” The article was written as a supplement to Psychiatric Times and provided helpful information on the recent literature on tardive dyskinesia (TD), the signs and symptoms of TD, risk factors and epidemiology, treatment and screening. It also contained concise summaries of several studies of TD. Overall, it appears to be an accessible article with a wealth of information on TD. But like a pitch from a pharmaceutical sales rep, attached to the end of the article is the medication guide for Ingrezza (valbenazine), one of two FDA-approved medications to treat TD, and a full-page color ad by Neurocrine Biosciences for Ingrezza.

The attachment of the advertisement and medication guide for Ingrezza left me wondering whether “Advances in Tardive Dyskinesia” was truly a review of the recent literature or just an advertisement. I don’t know if the author knew his article would have these attachments, but they left me wondering how objective the article was. It was formatted like a journal article, but as it was not published in a peer-reviewed journal; it did not have to go through that process. So, I question the representativeness of the “concise summaries of selected articles” reviewed in the article and whether there is another perspective of TD and its treatment.

Peter Breggin M.D. has a “TD Resources Center” for prescribers, scientists, professionals, patients and families that presents an opposing view of TD. He considers TD to be an iatrogenic disorder, largely from the use of antipsychotic drugs. Breggin said: “TD is caused by all drugs that block the function of dopamine neurons in the brain. This includes all antipsychotic drugs in common use as well as a few drugs used for other purposes.” In what follows, I will compare selections from the “Advances in Tardive Dyskinesia” to information available on Dr. Breggin’s website.

“Advances in Tardive Dyskinesia” said the causes of TD were unknown, but likely to be complex and multifactorial. It suggested there is evidence that multiple genetic risk factors interact with nongenetic factors, contributing to TD risk. It quoted the DSM-5 definition of TD, which said it developed in association with the use of a neuroleptic (antipsychotic) medication. Note that TD is narrowly conceived as related to the use of antipsychotics. This then necessitate the existence of something called spontaneous dyskinesia, which is an abnormal movement in antipsychotic-naïve patients that is “indistinguishable from TD.” A review of antipsychotic-naïve studies found that the prevalence of spontaneous dyskinesia ranged from 4% to 40% and increased with age.

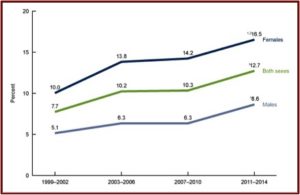

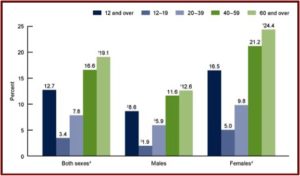

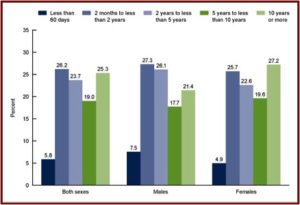

TD was said to be highly prevalent in patients treated with antipsychotics, but the rate of TD was lower, but not negligible, in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics compared to those treated with first-generation antipsychotics (21% versus 30%). The cumulative duration of antipsychotic exposure was said to be an important consideration when estimating these TD rates, which can be diagnosed after as little as 3 months of cumulative antipsychotic treatment. TD can emerge more rapidly in some patients, especially the elderly.

Alternatively, Peter Breggin said TD is “a group of involuntary movement disorders caused by drug-induced damage to the brain.” As noted above, he conceives TD as caused by all drugs that block the function of dopamine in the brain. Included are all antipsychotics “as well as a few drugs used for other purposes.” He said TD begins to appear within 3-6 months of exposure to antipsychotics, but cases have occurred from one or two doses.

The risk of developing TD, according to Breggin, was high for all age groups, including young adults: 5% to 8% of younger adults per year who are treated with antipsychotics. The rates are cumulative, so that by three years of use, 15% to 24% will be afflicted. “Rates escalate in the age group 40-55 years old, and among those over 55 are staggering, in the range of 25%-30% per year.” One article by Joanne Wojcieszek, “Drug-Induced Movement Disorders,” said the risk factors for developing TD increase with advancing age. “In patients older than age 45 years, the cumulative incidence of TD after neuroleptic exposure is 26%, 52%, and 60% after 1, 2, and 3 years respectively.” There is more detailed information in his Scientific Literature section. Regarding the newer, second-generation antipsychotics , he thought they had similar rates to first-generation antipsychotics. Breggin said:

Drug companies have made false or misleading claims that newer antipsychotic drugs or so-called atypicals are less likely to cause TD than the older ones. Recent research [more information in his Scientific Literature section], much of it from a large government study called CATIE, have dispelled this misinformation. Considering how huge the TD rates are, a small variation among drugs would be inconsequential. All the antipsychotic drugs with the possible exception of the deadly Clozaril, cause TD at tragically high rates. Since all these drugs are potent dopamine blockers, there should have been no doubt from the beginning that they would frequently cause TD.

Psychiatric Times linked several articles on tardive dyskinesia together, including, “Not All That Writhes Is Tardive Dyskinesia” and others like “Tardive Dyskinesia Facts and Figures,” “A Practical Guide to Tardive Dyskinesia,” and others. The information in the articles generally seems to acknowledge TD as being associated with long-term exposure to dopamine receptor antagonists (Although “Not All That Writhes Is Tardive Dyskinesia” softened that association by making the TD-spontaneous dyskinesia distinction), which include both first and second-generation antipsychotics. In “Tardive Dyskinesia Facts and Figures,” Lee Robert said a survey of patients taking antipsychotics found that 58% were not aware that antipsychotics can cause TD. An estimated 500,000 persons in the US have TD. 60% to 70% of the cases are mild, and 3% are severe. “Persistent and irreversible tardive dyskinesia is most likely to develop in older persons. . . Tardive dyskinesia is not rare and anyone exposed to treatment with antipsychotics is at risk.”

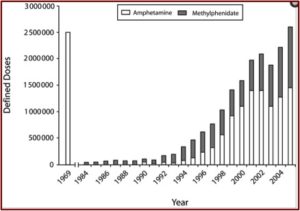

GoodTherapy gave the following information on “Typical and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents.” The website noted antipsychotic medications, also known as neuroleptics or major tranquilizers, have both a short-term sedative effect and the long-term effect of reducing the chances of psychotic episodes. There are two categories of antipsychotics, typical or first-generation antipsychotics and atypical or second-generation antipsychotics. First generation antipsychotics were said to have a high risk of side effects, some of which are quite severe. “In response to the serious side effects of many typical antipsychotics, drug manufacturers developed another category referred to as atypical antipsychotics.”

Both generations of antipsychotics tend to block receptors in the dopamine pathways or systems of dopaminergic receptors in the central nervous system. “These pathways affect thinking, cognitive behavior, learning, sexual and pleasure feelings, and the coordination of voluntary movement. Extra firing (production of this neurotransmitter) of dopamine in these pathways produces many of the symptoms of schizophrenia.” The discovery of clozapine, the first atypical antipsychotic, noted how this category of drugs was less likely to produce extrapyramidal side effects (tremors, paranoia, anxiety, dystonia) in clinically effective doses than some other antipsychotics.

Wikipedia said as experience with atypical antipsychotics has grown, several studies have raised the question of the wisdom of broadly categorizing antipsychotic drugs as atypical/second generation and typical/first generation. “The time has come to abandon the terms first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics, as they do not merit this distinction.”

Although atypical antipsychotics are thought to be safer than typical antipsychotics, they still have severe side effects, including tardive dyskinesia (a serious movement disorder) neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and increased risk of stroke, sudden cardiac death, blood clots and diabetes. Significant weight gain may occur.

In another publication, “Tardive Dyskinesia,” Vasan and Padhy also said TD was caused by long-term exposure to first and second-generation antipsychotics, some antidepressants (like fluoxetine), lithium and certain antihistamines. They said there was some evidence that the long-term use of anticholinergic medications may increase the risk of TD. See “The Not-So-Golden Years” for more on anticholinergics. Vasan and Padhy said TD was seen in patients with chronic exposure to dopamine D2 receptor blockade and rarely in patients who have been exposed to antipsychotics less than three to six months. “A diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia is made after the symptoms have persisted for at least one month and required exposure to neuroleptics for at least three months.”

They cautioned against the chronic use of first-generation antipsychotics, saying they should be avoided whenever possible. “Primary prevention of tardive dyskinesia includes using the lowest effective dose of antipsychotic agent for the shortest period possible.” The authors noted the FDA’s approval of Ingrezza (valbenazine) to treat TD, saying that early data indicated it was safe and effective in abolishing TDs. “However, the study was conducted by many physicians who also received some type of compensation from the pharmaceutical companies- so one has to take this data with a grain of salt until more long-term data are available.”

So, where does all of this leave us with regard to antipsychotics and tardive dyskinesia? Contrary to what “Advances in Tardive Dyskinesia” said, the cause of TD is known. According to Dr. Peter Breggin and others, TD is caused by drugs that block the function of dopamine receptors in the brain. The risk of developing TD is present for all ages, although older adults are at higher risk of suffering this adverse side effect. And the risk of TD increases with the continued use of antipsychotics, perhaps as high as 26%, 52%, and 60% after 1, 2, and 3 years respectively of cumulative use.

Narrowly defining TD (as the DSM does) leads to the confounding invention of spontaneous dyskinesia—that is said to be indistinguishable from TD. The logic here seems circular. If TD is defined as caused by antipsychotics (which seems to mean primarily first generation antipsychotics), then dyskinesia independent of antipsychotics can’t be TD, because TD is only found with antipsychotics.

The so-called first-generation antipsychotics and second-generation antipsychotics equally put the individual at risk of developing TD and should be used at the lowest possible dose for the shortest time—if at all. Dr. Breggin said: “Since all these drugs are potent dopamine blockers, there should have been no doubt from the beginning that they would frequently cause TD.” Disregarding the fact that this drug action common to all antipsychotics perpetuates what seems to be an unnecessary and inaccurate distinction between first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics. So, if it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, isn’t it a duck?

See “Downward Spiral of Antipsychotics” for more on the concerns with antipsychotics.