Fluctuations in the Heroin Market

The 2016 World Drug Report (2016 WDR) is a good-news bad-news source of information on global opiate statistics. The good news is that global opium production fell by 38% in 2015. The decrease was primarily the result of a decline in opium production in Afghanistan, which fell 48% compared to 2014. This was mainly because of poor yields in the country’s southern provinces. Despite this, Afghanistan was still the world’s largest opium producer, accounting for 70% of global opium production.

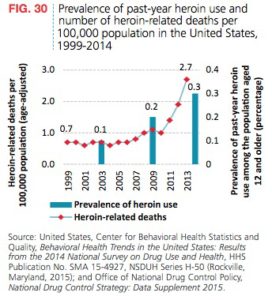

The bad news is that despite the drop in production, the global number of opiate users has remained relatively stable. And opium production in Latin America, mostly in Mexico, Columbia and Guatemala, more than doubled from 1998-2014. Central and South American production accounts for 11% of the estimated global opium production. Also, in North America, heroin use and heroin-related deaths have continued to rise. In both cases, the increases were roughly three times the 1999 levels. See the following chart from the 2016 WDR.

In 2014, the largest seizures of opiates were in South-West Asia, with Europe next in line. The Islamic Republic of Iran reported the largest opiate seizures worldwide, accounting for 75% of global opium seizures and 17% of global heroin seizures. The next largest heroin seizures were from Turkey (16% of global heroin seizures), China (12%), Pakistan (9%), Kenya (7%), the U.S. (7%), Afghanistan (5%), and the Russian Federation (3%). Iran is the first stop on the so-called “Balkan route” of opiate distribution. From there the route travels into Turkey, and onto South-Eastern Europe, where it is distributed throughout Western and Central Europe. “Seizure data suggest that the Balkan route, which accounts for almost half of all heroin and morphine seizures worldwide, continues to be the world’s most important opiate trafficking route.”

In 2014, the largest seizures of opiates were in South-West Asia, with Europe next in line. The Islamic Republic of Iran reported the largest opiate seizures worldwide, accounting for 75% of global opium seizures and 17% of global heroin seizures. The next largest heroin seizures were from Turkey (16% of global heroin seizures), China (12%), Pakistan (9%), Kenya (7%), the U.S. (7%), Afghanistan (5%), and the Russian Federation (3%). Iran is the first stop on the so-called “Balkan route” of opiate distribution. From there the route travels into Turkey, and onto South-Eastern Europe, where it is distributed throughout Western and Central Europe. “Seizure data suggest that the Balkan route, which accounts for almost half of all heroin and morphine seizures worldwide, continues to be the world’s most important opiate trafficking route.”

The massive decline in opium production of almost 40 per cent in 2015 is unlikely, however, to result in a decline of the same magnitude within a year in either the global number of opiate users or the average per capita consumption of opiates. It seems more likely that inventories of opiates, built up in previous years, will be used to guarantee the manufacture of heroin (some 450 tons of heroin per year would be needed to cater for annual consumption) and that only a period of sustained decline in opium production could have any real effect on the global heroin market.

In 2015 Bloomberg published an article with three maps of global drug smuggling routes. The major opiate producers are: Afghanistan, Myanmar, Laos, Mexico and Columbia. The opiate map illustrates the vast reach of the so-called Balkan route. The Americas are primarily supplied with opiates grown in Mexico and Columbia. More than 70% of all heroin and morphine seizures in the Americas were in the U.S. between 2009 and 2014. Seizures more than doubled from around 2 tons per year from 1998-2008 to 5 tons per year from 2009-2014. Heroin trafficking and use was seen in 2015 as the main national drug-related threat in the US, according to the 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA).

The 2015 NDTA reported that heroin was available in larger quantities, used by larger numbers of people, and caused more overdose deaths than 2007. The increased demand and use of heroin is driven by greater availability and controlled prescription drug (CPD) abusers switching to heroin. Cheaper prices for heroin contribute to the switch as well.

Increases in overdose deaths are driven by several factors. The purity of heroin has increased in some areas. New heroin users switching from prescription opioids are used to the set dosage amounts potency of prescription drugs. Illicitly–manufactured drugs can vary widely in their purity, dosage and adulterants. Over the past few years the use of highly toxic adulterants like fentanyl (20 to 40 times stronger than heroin) in certain markets has also added to the increase in overdose deaths. Then there are heroin users who stopped using for a while (from treatment or incarceration) whose tolerance has decreased because of their abstinence.

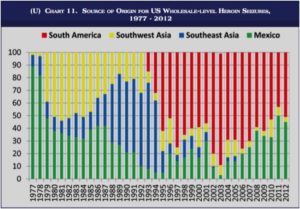

Most of the heroin in the US today comes from Mexico and Columbia. Columbian heroin is still the predominant type available in the Eastern US. While Southeast Asian heroin, largely from Afghanistan dominates the global market, very little makes its way to the US. Southeast Asian heroin was the dominant supplier of heroin in the US at one time. But it no longer can compete with the transportation and distribution networks of the Mexican and Columbian drug cartels. Se the following chart from the 2015 NDTA.

The Mississippi River has been a dividing line in the US heroin market for the past 30 years, with Mexican black tar and brown powder heroin west of the Mississippi and white powder heroin from South America in the East. There is increasing evidence that Mexican drug cartels are processing their own white powder heroin and mixing white heroin with Mexican brown powder heroin to create a more appealing product to the Eastern US markets. See charts 12 and 13 in the 2015 NDTA for further information on the availability of heroin types purchased in Eastern and Western cities.

The Mississippi River has been a dividing line in the US heroin market for the past 30 years, with Mexican black tar and brown powder heroin west of the Mississippi and white powder heroin from South America in the East. There is increasing evidence that Mexican drug cartels are processing their own white powder heroin and mixing white heroin with Mexican brown powder heroin to create a more appealing product to the Eastern US markets. See charts 12 and 13 in the 2015 NDTA for further information on the availability of heroin types purchased in Eastern and Western cities.

The suspected production of white powder heroin in Mexico is important because it indicates that Mexican traffickers are positioning themselves to take even greater control of the US heroin market. It also indicates that Mexican traffickers may rely less on relationships with South American heroin sources-of-supply, primarily in Colombia, in the future. If Mexican TCOs [transnational criminal organizations] can produce their own white powder heroin, there will be no need to purchase white powder heroin from South America to meet demand in the United States. This would also reinforce Mexican TCOs’ poly-drug trafficking model and ensure their domination of all major illicit drug markets (heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and marijuana) in the United States.

Mexican TCOs have been increasing their cultivation of opium poppies, to an estimated 17,000 hectares in 2014. This can potentially produce up to 42 metric tons of heroin. Switching to opium cultivation from marijuana cultivation may be at least partly due to the lowered demand for illicit marijuana in the US because of the legalization movement. See “The Economics of Heroin” for more information.

The number of heroin users reporting they used heroin over the past month increased 80% between 2007 and 2012. Of the total number of heroin-related treatment admissions in 2012, 67.4% reported daily use and 70.6% reported their preferred route of use was by injection. Heroin treatment admissions were consistently highest in the New England and Mid-Atlantic states. There are also high rates of repeated treatment among heroin users. Eighty percent of the primary heroin users admitted to treatment in 2012 reported previous treatment; 27% had been in treatment five or more times.

Most opioid users in the 1960s began by using heroin. But that steadily changed until 75% of heroin-users in the early 2000s reported they began by using prescription opioids. The number of people using illicit prescription opioids who switched to heroin was a relatively small percentage of the total number of prescription drug abusers at 3.6%. But it represented 79.5% of new heroin users. Heroin use was 19 times higher among individuals who had previously used pain relievers non-medically.

The reformulation of OxyContin in 2011 is seen as helping to curb the abuse of the drug. In 2011 emergency department visits involving oxycodone declined for the first time since 2004. Overdose deaths from opioid analgesics also began to decrease in 2011. But remember, CPD abusers have been switching to heroin and seem to be contributing to the dramatic increase in overdose deaths from heroin.

The number of heroin overdose deaths increased 244% between 2007 and 2013. Keep in mind that heroin deaths are undercounted. This occurs because of the differences in state reporting procedures for reporting drug-related deaths; and because heroin metabolizes very quickly into morphine. A metabolite unique to heroin, 6-monoaceytlmorphine (6-MAM), quickly metabolizes into morphine erasing the biochemical evidence for heroin use. So many heroin deaths get reported as morphine-related deaths. So what does the future hold for heroin use in the US? The 2015 NDTA concluded the current outlook for the near future is more of the same.

Heroin use and overdose deaths are likely to continue to increase in the near term. Mexican traffickers are making a concerted effort to increase heroin availability in the US market. The drug’s increased availability and relatively low cost make it attractive to the large number of opioid abusers (both prescription opioid and heroin) in the United States.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) publishes a yearly report giving a global overview of the supply and demand of various drugs and their impact on health.