Doubling the Risk of Overdose

In February of 2018 The New England Medical Journal published an editorial titled “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem.” The authors said that between 1996 and 2013 the number of prescriptions written for benzodiazepines increased by 67% and the quantity of pills dispensed tripled. The number of overdose deaths from benzodiazepines also increased. Three fourths of those deaths involved an opioid; and co-prescribing rates of opioids and benzos have almost doubled since 2001. “Despite this trend, the adverse effects of benzodiazepine overuse, misuse, and addiction continue to go largely unnoticed.”

Both Medscape (“Benzodiazepine Harms Overlooked, Especially in Older Adults”) and Mad in America (“Psychiatrists Warn Policymakers Benzodiazepine Overuse Could Lead to Next Epidemic”) cited the editorial and quoted the above comment. But they seem to have spun the article’s content in different directions. The Medscape article was primarily about benzodiazepine use among older adults, as the title suggests, so readers would likely get the impression ”Our Other Prescription Drug Problem” was as well. The NEMJ article cited and discussed two additional articles on the problems of “benzodiazepine use among the elderly.” But that is not what “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem” was about. In fact, seniors using benzos was not even mentioned there.

Another slight-of-hand was with how the concluding paragraph of the Medscape article sanitized the rhetoric of the authors of “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem,” which referred to opioids and benzodiazepines as “life-threatening drugs.” The final paragraph of the Medscape article is followed by the original paragraph quoted in its entirety from “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem.”

If measures designed to discourage people from using opioids divert them to benzodiazepines instead, “[i]t would be a tragedy,” Lembke and colleagues conclude in their editorial. “We believe that the growing infrastructure to address the opioid epidemic should be harnessed to respond to dangerous trends in benzodiazepine overuse, misuse, and addiction as well.” (Medscape)

It would be a tragedy if measures to target overprescribing and overuse of opioids diverted people from one class of life-threatening drugs to another. We believe that the growing infrastructure to address the opioid epidemic should be harnessed to respond to dangerous trends in benzodiazepine overuse, misuse, and addiction as well. (NEMJ; emphasis added)

The readers of Medscape did not get a clear sense of what Dr. Lembke and her coauthors were saying in “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem.” Lembke et al. said benzos had proven utility if they were used intermittently and for less than 1 month at a time. “But when they are used daily and for extended periods, the benefits of benzodiazepines diminish and the risks associated with their use increase.” They noted how prescribers often don’t realize the potential problems with benzos and that safer alternatives are available.

Many prescribers don’t realize that benzodiazepines can be addictive and when taken daily can worsen anxiety, contribute to persistent insomnia, and cause death. Other risks associated with benzodiazepines include cognitive decline, accidental injuries and falls, and increased rates of hospital admission and emergency department visits. Fortunately, there are safer treatment alternatives for anxiety and insomnia, including selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and behavioral interventions.

Lembke et al. did say some patients could benefit from long-term benzodiazepine use, but suggested it was best to avoid daily dosing. They also referred to the newer, highly potent forms of benzodiazepines on the illicit drug market, which are often indistinguishable from prescription benzodiazepines and said they were: “potentially as deadly as the synthetic opioid analogue fentanyl.” They called for efforts to shut down illegal online pharmacies and drug-trafficking networks where individuals purchase illicit benzodiazepines, particularly the “superpotent analogues.”

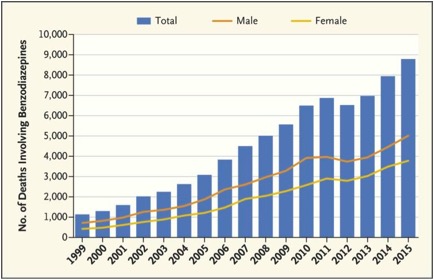

The Mad in America article by Zenobia Morrill had several quotes from the original editorial and additional discussion of its contents, which addressed how benzodiazepine overuse, misuse and addiction has not received the attention that opioid overuse, misuse and addiction has received. And Morrill did not spin the original editorial. Her article also reproduced the following graph of overdose deaths in the U.S. involving benzodiazepines found in “Our Other Prescription Drug Problem.”

Morrill said Lembke et al. hypothesized the acceleration of benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths may be overlooked because the concurrent use of opioids in 75% of those deaths. Given the dangers of benzodiazepine use alone and in conjunction with opioids, providers should strive to taper benzodiazepines in patients who have been stabilized using opioid-agonist therapy, “taking into account patient’s preferences, the risks and benefits of benzodiazepines, and possible alternatives.”

Morrill said Lembke et al. hypothesized the acceleration of benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths may be overlooked because the concurrent use of opioids in 75% of those deaths. Given the dangers of benzodiazepine use alone and in conjunction with opioids, providers should strive to taper benzodiazepines in patients who have been stabilized using opioid-agonist therapy, “taking into account patient’s preferences, the risks and benefits of benzodiazepines, and possible alternatives.”

Hernandez et al. looked at how the risk of overdose changed over time with concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use in “Concurrent Opioid and Benzodiazepine Use and Risk of Opioid-Related Overdose.” The researchers looked at a random sample of data among Medicare Part D beneficiaries between 2013 and 2014. Their main outcome of interest was opioid-related overdoses—including fatal and nonfatal overdoses. They found that during the first 90 days of concurrent benzodiazepine use, there was a fivefold increase in the risk of opioid-related overdose.

Our study yielded 3 main findings. First, we found that 29% of Medicare Part D beneficiaries who did not have cancer and who used prescription opioids concurrently filled prescriptions for benzodiazepines. Second, we found that the risk of opioid-related overdose is particularly high during the first days with concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use and then decreases over time. Specifically, during the first 90 days of concurrent benzodiazepine use, the risk of opioid-related overdose is 5 times higher compared with opioid use alone. Third, the numbers of opioid and benzodiazepine prescribers were associated with an increased likelihood of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use and an increased risk of overdose and were strong confounders in examining the association between concurrent use and overdose.

Among patients who used both medications longer than 90 days and did not overdose, they still had almost double the risk of overdose between 91 and 180 days of concurrent use. Concurrent use without overdose for more than 180 days did not predict an increased risk of overdose. But those results did not mean patients exposed to concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use for longer time periods had a lower risk of overdose. “In fact, the longer the duration of concurrent use, the higher the risk of overdose, because the increased risk of overdose predicted during each time window (1-90, 91-180, 181-270, and 271 days of concurrent use) would be cumulative.”

Hernandez et al. said that despite the known increased risk of overdose associated with concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use, “it is very common in the Medicare population.” They said policy interventions should advocate against concurrent use. Performance measures should be redefined to prevent or restrict their concurrent use. The risk of overdose is also exacerbated by fragmented medical care.

Overall, these results demonstrate the important role that fragmentation of care plays in the inappropriate use of opioids and in the subsequent risk of overdose, and warrant the extended use of prescription monitoring programs and the implementation of new policy interventions that further control the receipt of opioid prescriptions by multiple prescribers.

The bottom line is the concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines at least doubles the risk of an overdose.