Naloxone Works If You Can Afford It

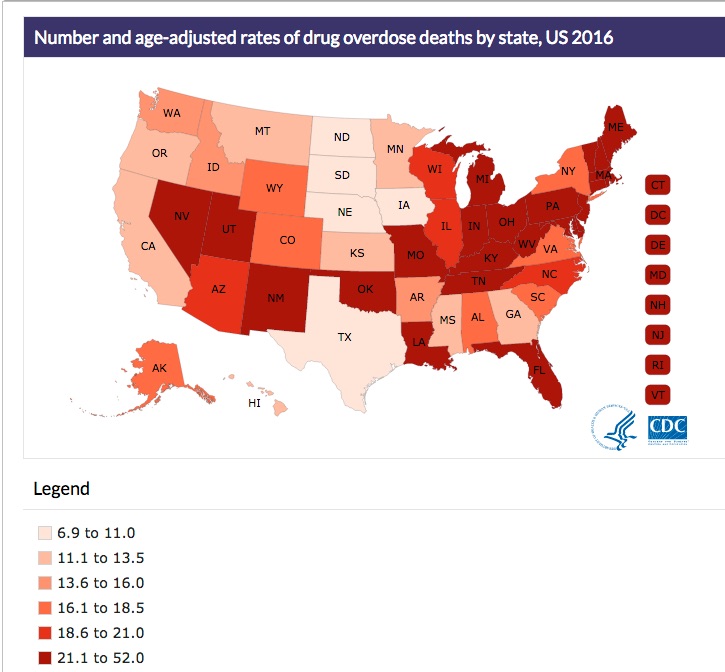

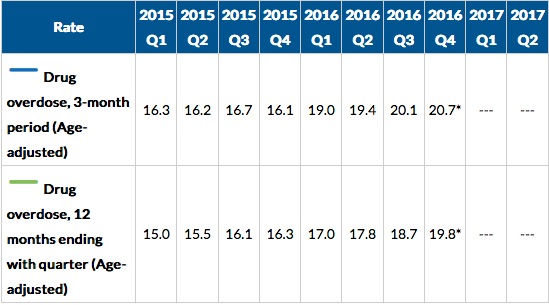

The CDC has an interactive presentation of data on drug overdose death counts at: “Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts.” The data visualization is based on current mortality data in the National Vital Statistics System. You can choose between dashboards showing drug overdose deaths from December of 2014 (47,523) to December of 2017 (70,467); or you can examine state-by-state reports on drug over dose deaths between December 2016 and December 2017. You can also see a dashboard showing drug overdose deaths by drug or drug class, which indicated that 47,705 people died from opioid overdoses in a 12-month period ending in December of 2017. If naloxone had been administered to them, 93.5% might have survived and 84.3% of those survivors could have still been alive a year later. Naloxone works.

The above predictions were based on a research study reported in a CNN article. The lead author of the study was Dr. Scott Weiner, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Pessimists might point out the study also found there was a 1 in 10 chance of those individuals not surviving a year (the title to the CCN article itself contained the phrase: “many recipients don’t survive a year”). Thirty-five percent of those deaths were from another opioid overdose. However, Weiner said: “The lesson learned is not that naloxone is failing; it’s working.” Naloxone works, but it doesn’t treat the underlying problem, he added.

The U.S. Surgeon General issued a public health advisory on April 5, 2018, urging more Americans to learn to use and carry naloxone. He encouraged individuals to learn the signs of opioid overdose; to get trained to administer naloxone in the case of a suspected emergency; and to talk to your doctor or pharmacist about obtaining naloxone. Prescribers, pharmacists and treatment providers were urged to learn how to identify patients at high risk of overdose; prescribe or dispense naloxone to individuals who are at elevated risk for opioid overdose and to their friends and family. He also said:

Increasing the availability and targeted distribution of naloxone is a critical component of our efforts to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths and, when combined with the availability of effective treatment, to ending the opioid epidemic.

Caroline Engelmayer reported in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette how David Lettrich was one of these individuals who carried naloxone; knew how to use it and learned the signs of opioid overdose. Along with another person, Stuart Fisk, who was walking down the street to get coffee, he was able to administer CPR and Narcan—a brand-name version of naloxone—to the unconscious man and he save his life. David Letterich is the founder and director of Bridge to the Mountain, a nonprofit organization serving the homeless and addicted individuals in Pittsburgh. Stuart Fisk is a nurse practitioner with Allegheny Health Network, but their particular interests and skill sets weren’t relevant to what they accomplished. Anyone can carry and be trained to administer naloxone.

The Post-Gazette article pointed out how increased availability of naloxone is essential. Alice Bell, the coordinator of Prevention Point Pittsburgh’s Overdose Prevention Project, said: “In 2017 there is easily twice as much naloxone given out to the community as there was in 2016.” Increased availability means multiple doses can be distributed to residents. “While a single dose of naloxone revives some people, others sometimes require up to six or seven doses.” David Lettrich said: “The only way naloxone works is if it can be distributed in surplus.”

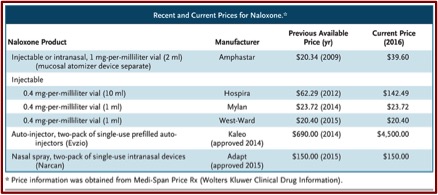

But there is a problem; the price of naloxone and naloxone-based products has skyrocketed. “In 2009, one vial of naloxone sold by the pharmaceutical company Amphastar cost roughly $20. By 2016, its price had nearly doubled, to $39.60.”

Naloxone used to be a “very cheap” generic drug that cost a dollar or two per dose, Mr. Fisk said. Now, an intranasal device with two doses costs $150, according to Mr. Fisk, and an automated naloxone machine that speaks instructions on how to administer the medicine sells for over $600.

The Bill of Health, a Harvard blog of the Petrie-Flon Center, provided some helpful background information on naloxone. Naloxone was first developed and patented in 1961 as a medication to reverse constipation in opioid patients. The FDA approved its use to reverse opioid overdose in 1971. And naloxone comes in several forms. It can be administered as an intravenous or intramuscular solution and as a nasal spray. It also can be given in tablet form as an abuse deterrent (ReVia). And it comes as an extended-release injectable, also as an abuse deterrent (Vivitrol).

Naloxone has been historically inexpensive and pharmaceutical companies really didn’t care much about it. Only six pharmaceutical companies even made the drug prior to 2014. It wasn’t until the onset of the opioid epidemic, and public health initiatives that allowed public access to this drug, that prices began to soar.

Naloxone’s wholesale generic cost is around $20 for a single dose. The nasal spray product, known as Narcan, costs $133 to $160 for a two-dose kit. A top-of-the-line two-injector kit known as Evizio that talks you through injecting the naloxone starts at $3,758. The Evzio price is a 680 percent increase over its original price in 2014. “These price increases came when the opioid epidemic was at its peak, and they came without any explanation.” There have been actions taken by several states to limit these increases, but little done in the way of federal regulation to enforce them.

The “patented” delivery systems seem to be the justification for the exorbitant cost of Narcan and Evizio. But decongestants and topical steroids use delivery systems similar to Narcan and these methods cost no more than $10 to $20 dollars per unit, not $160. “An atomizer device that can be just as efficacious a means of drug-delivery sells for around $7.00.” Auto-injectors, around since the 1970s to deliver anti-nerve agents, consist of little more than plastic casing, a pressure activated spring and a needle. Remember the outcry over the unjustifiable cost of the EpiPen, a similar delivery system to Evizio costing ($630)?

The exorbitant cost of these drugs crosses an ethical boundary as well. Ethical sales principles ensure that the cost of an item can be justified, and that the buyer is not being exploited. There has been no evidence to date to support the increased cost of either naloxone product. Furthermore, any parent with a child, any spouse, friend or even a neighbor of someone with substance abuse disorder would pay any price to save their loved one’s life. To take advantage of that is simply unethical and detrimental to society.

Naloxone has gone from a $21 million per year industry before 2014 to $274 million per year since 2015. “There is no doubt: pharmaceutical companies are making money off the opioid epidemic. Additionally, those who need this drug the most, often don’t have access to it. They are the under- or uninsured, so waving a co-pay is moot.”

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, a potential solution to the exorbitant cost of these drugs is to develop an over-the-counter naloxone product. Harm Reduction Therapeutics is currently raising money and preparing for a clinical trial for its own over-the-counter naloxone product. Michael Hufford, the co-founder and CEO of Harm Reduction Therapeutics, “aims to sell naloxone at the lowest possible cost to increase access to the drug.” If you know any venture capitalists, tell them about Harm Reduction Therapeutics.

Dr. Hacker, director of the Allegheny County Health Department supports the idea of an over-the-counter version of naloxone and mentioned it to some federal legislators. The risks associated with the drug are incredibly low. Dr. Hufford wants to make naloxone widely available at minimal cost. He said: “Just like you can go anywhere and buy Band-Aids and Tylenol, we think naloxone should be that available.”

The question is will Harm Reduction Therapeutics be able to successfully navigate the gauntlet of competing lobbyists with the FDA and federal government from Endo Health Solutions, which manufactures Narcan and Kaleo, which manufactures Evzio. Naloxone works, but only if you can afford it. Let’s see if we can make that true for the next 47,705 people dying from opioid overdoses.