Sure Cure for Drunkenness

Researchers at the University of North Carolina have identified a circuit between two regions of the brain that are thought to control binge drinking. The two areas—the extended amygdala and the ventral tegmental area (VTA)—have been implicated in past studies of alcohol binge drinking. The results of this study provide the first direct evidence that inhibiting a circuit between two brain regions may protect against binge drinking. Todd Thiele, who directed the research, said: “If you can stop somebody from binge drinking, you might prevent them from ultimately becoming alcoholics. We know that people who binge drink, especially in their teenage years, are much more likely to become alcoholic-dependent later in life.” But so far, the research has only been demonstrated with mice.

Thiele and his team demonstrated that alcohol activates the CRF (corticotropin releasing factor) neurons in the extended amygdala, which in turn act on the ventral tegmental area. Applied to humans, these observations suggest that when someone drinks alcohol, CRF neurons in human brains are activated in a similar manner, promoting continued and excessive drinking. Thiele thought their findings could be relevant for future pharmacological treatments to help curb binge drinking. Although Thiele and his team didn’t connect their research to a particular pharmacological treatment for binge drinking, others did.

Writing for the Telegraph last year, Laura Donnelly connected the dots between the UNC team of researchers and a drug called Selincro (nalmefene). Selincro was approved by the National Health Service (NHS) in Britain to help individuals cut back on their alcohol intake. It costs £3 ($3.96) and is to be taken as needed to stave off the desire to drink. Writing for the Mirror, Paul Christian’s headline was designed more to catch your attention than communicate truth: “New £3 pill to ‘cure’ alcoholism can stop binge boozing.”

Paul Fuhr was more cautious in his article for After Party Magazine, “Pill Could Cure Alcoholism, Binge Drinking.” His review accurately pointed out that Selincro is recommended for heavy drinkers. “In targeting weekend warriors rather than career alcoholics, the drug becomes less a cure-all than a solid first step toward sobriety.” He thought the implication of using Selincro to treat binge drinking was more intriguing than the reported effectiveness of the pill.

The prospect of a $4 pill that helps binge drinkers from falling down the alcoholic rabbit hole is an intriguing one but, in my opinion, could cause more damage than good. The pill’s very existence would feed the very problem it’s trying to combat, serving as something of a security blanket for people who know they can take a pill. It’s more important that researchers have uncovered the link between brain areas than designing a drug to flip the switch.

I think Fuhr is exactly right in his assessment that uncovering the link between brain areas is more important than a drug designed to “flip the switch.” I also agree that any drug used to turn this neurochemical circuit off and on will likely do more harm than good, aggravating the problem it is supposed to relieve. Its effectiveness is contingent upon the person actually taking the Selincro. And since it will also limit the euphoric effects of the alcohol as well as the cravings, if you don’t want to limit the euphoria, you won’t take it.

It may disrupt cravings and limit the euphoria from drinking, and this could limit how much you drink; but it won’t neutralize the other physiological effects of the alcohol you do drink. Physiological conditions from heavy drinking (anemia, cancer, cardiovascular disease, cirrhosis, gout, high blood pressure, pancreatitis, to name a few) may not improve—and could even progress—with continued drinking. It also won’t limit you blood alcohol level (BAL), so alcohol can still effect your judgment and decision making. Your self-control will still be blunted.

And this isn’t a new drug or a new treatment method, as some of the media seems to imply. The Sinclair Method actually recommends intentionally drinking after taking naltrexone. It conceives alcoholism to be a learned disorder. Limiting the euphoric reward of drinking is alleged to “cure” your alcoholism by systematically extinguishing the high. They should have remembered from behaviorism 101 that intermittent reinforcement (flicking the alcohol euphoria switch off-and-on) makes it more difficult to extinguish a behavior. See “A ‘Cure’ for Alcoholism.”

Another issue lies with the mixed results of research studies done with nalmefene on humans.

Two French researchers published “Nalmefene: a new approach to the treatment of alcohol dependence” in the journal Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. They reviewed the recent scientific literature on nalmefene that described its value in reducing alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients. They noted where nalmefene was well tolerated. Its most common side effects were nausea, dizziness, insomnia and headache—which were mild or moderate and of short duration. Now the adverse effects disclaimer:

Selincro® must not be used in people who are hypersensitive (allergic) to nalmefene or any of its other ingredients. It must not be used in patients taking opioid medicines, in patients who have current or recent opioid addiction, patients with acute symptoms of opioid withdrawal, or patients in whom recent use of opioids is suspected. It must also not be used in patients with severe liver or kidney impairment or a recent history of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome (including hallucinations, seizures, and tremors).

Paille and Martini said the available studies on nalmefene showed it to be more effective than placebo in reducing the number of heavy drinking days and total alcohol consumption. They lamented that the reduction of alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients is not more widely recognized as a treatment objective. They pointed to the February 2013 approval of nalmefene by the European Medicines Agency with the following indications:

Selincro is indicated for the reduction of alcohol consumption in adult patients with alcohol dependence who have a high drinking risk level, without physical withdrawal symptoms and who do not require immediate detoxification.

Selincro should only be prescribed in conjunction with continuous psychosocial support focused on treatment adherence and reducing alcohol consumption.

Selincro should be initiated only in patients who continue to have a high drinking risk level two weeks after initial assessment.

The European Medicines Agency limits the use of Selincro (nalmefene) in patients with a high drinking risk level that continues two weeks after an initial assessment. These patients should not exhibit physical withdrawal symptoms upon decreased alcohol consumption; and should not be in need of detoxification. And it should only be initiated in patients who remained in “continuous psychosocial support” that focused on treatment adherence and reducing alcohol consumption. In others words, use nalmefene as a method to reduce alcohol consumption and not as a method to more effectively control the negative consequences of drinking large amounts of alcohol. Paille and Martini concluded:

Nalmefene appears to be an effective treatment to reduce alcohol consumption in alcohol-dependent patients not wanting to become totally abstinent. It differs from other drug therapies essentially by replacing systematic dosing by “as-needed” dosing adapted to the patient’s clinical situation on a day-to-day basis. Patients therefore take nalmefene when they feel that alcohol consumption is imminent.

This is not the final word in nalmefene as a harm reduction tool with alcohol dependence. Palpacuer et al. published a literature review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished double-blind randomized controlled trials of nalmefene: “Risks and Benefits of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adult Alcohol Dependence.” Significantly, they used the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias in their screening of nalmefene trials for their methodological quality. Five randomized control studies with a total of 2,567 randomized participants were included in the main analysis. So what did the researchers find?

The researchers identified five RCTs that met the criteria for inclusion in their study. All five RCTs (which involved 2,567 participants) compared the effects of nalmefene with a placebo (dummy drug); none was undertaken in the population specified by the European Medicines Agency approval. Among the health outcomes examined in the meta-analysis, there were no differences between participants taking nalmefene and those taking placebo in mortality (death) after six months or one year of treatment, in the quality of life at six months, or in a summary score indicating mental health at six months. The RCTs included in the meta-analysis did not report other health outcomes such as accidents. Participants taking nalmefene had fewer heavy drinking days per month at six months and one year of treatment than participants taking placebo, and their total alcohol consumption was lower. However, more people withdrew from the nalmefene groups than from the placebo groups, often for safety reasons. Thus, attrition bias—selection bias caused by systematic differences between groups in withdrawals from a study that can affect the accuracy of the study’s findings—cannot be excluded. Indeed, when the researchers undertook an analysis in which they allowed for withdrawals, the alcohol consumption outcomes did not differ between the treatment groups.

What do these findings mean?

These findings show that there is no high-grade evidence currently available from RCTs to support the use of nalmefene for harm reduction among people being treated for alcohol dependency. In addition, they provide little evidence to support the use of nalmefene to reduce alcohol consumption among this population. Thus, the value of nalmefene for the treatment of alcohol addiction is not established. Importantly, these findings reveal a lack of information on clinically relevant outcomes in the evidence that led to nalmefene approval by the European Medicines Agency. Thus, these findings also call into question the decisions of this and other regulatory and advisory bodies that have approved nalmefene on the basis of the available evidence from RCTs, and highlight the need for further RCTs of nalmefene compared to placebo and naltrexone for the indication specified in the market approval.

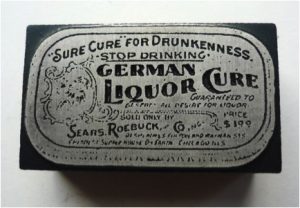

Paul Fuhr observed how the idea of miracle cures was as old as time itself, reminiscent of the days of patent medicines, like the German liquor cure sold at one time by Sears Roebuck and company for a buck.

Paul Fuhr observed how the idea of miracle cures was as old as time itself, reminiscent of the days of patent medicines, like the German liquor cure sold at one time by Sears Roebuck and company for a buck.

Culturally, we want to believe there is a “cure” for drunkenness in pill form that doesn’t require us to do the hard work of establishing and maintaining abstinence. My suggestion is to do the hard work.