Runaway Pharma Gravy Train

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) spent $27.5 million on lobbying in Washington last year. This was a new record, surpassing the previous high set in 2009, when PhRMA spent over $27 million. “The new record also topped 2017’s lobbying spend—$25.43 million, at a time when Trump was taking office and pricing was often on the airwaves—by about 8%.” The increases parallel steadily increasing prices for several years. For example, Medicaid drug costs nearly doubled to $31 billion.

Rep. Elijah Cummings initiated an investigation of 12 pharmaceutical companies in an effort to uncover pharma pricing practices. Cummings sent letters seeking information and documents about the companies’ pricing practices. This is the first step of the Committee on Oversight and Reform’s review of pricing practices. The Committee will also hold hearings in order to hear from experts and patients affected by rising drug prices.

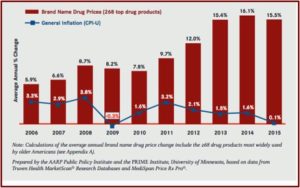

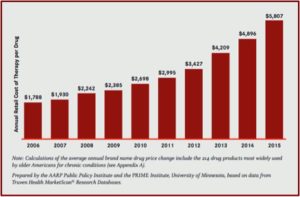

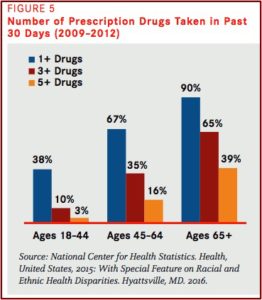

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projects that spending on prescription drugs will increase more rapidly than spending on any other health care sector over the next ten years. The federal government bears much of the financial burden of escalating drug prices through Medicare Part D, which provides drug coverage to approximately 43 million people. The government is projected to spend $99 billion on Medicare Part D in 2019. In 2016, the 20 most expensive drugs to Medicare Part D accounted for roughly $37.7 billion in spending.

The hearing was held on Tuesday, January 29, 2019, just two weeks after Rep. Cummings sent out his letters. There also seems to be bipartisan support to rein in drug prices. FiercePharma wondered whether this was real bipartisan unity or just talk. Rep. Mark Meadows, A Republican from North Carolina, said President Trump asked him to make sure the House knew on this issue, “He’s serious about working in a bipartisan way to lower prescription drug prices.” At the hearing Cummings acknowledged Trumps support, but said: “But tweets are not enough—we need real action and meaningful reforms.”

STAT News reported that Cummings is asking for “10 years worth of sales, revenue, pricing, rebate, discount, and commercialization data.” Additionally he’s asked for information detailing research and development expenses; information on patents and indications; employee compensation and bonus details; each company’s interaction with federal agencies; and details of company’s contracts with PBMs (pharmacy benefit mangers). Although his probe already includes most of the country’s largest pharmaceutical companies, he’s not finished. “There’ll be more.” Other congressional committees, such as Energy and Commerce and the Senate Finance Committee, are planning to do their own investigations.

The ten most expensive brand-name drugs accounted for $15.6 billion of spending in the catastrophic coverage phase of the Medicare Part D benefit in 2015. While the number of prescriptions fell by 17%, the Part D payments for brand-name drugs increased by 62% from 2011 to 2015. The payments for about 94% of commonly used medications more than doubled. The percentage of Medicare Part D beneficiaries who paid at least $2,000 out-of-pocket for their drugs almost doubled from 2011 to 2015. Cummings is focusing his inquiries on drugs that are among the costliest to Medicare Part D. If you’re curious, there is a link in the article to a list of the companies and drugs for conditions ranging from arthritis, cancer and cholesterol to diabetes.

An NPR and Center for Public Integrity investigation found drug companies have penetrated almost all aspects of the process that determines how their drugs are covered by taxpayers. Doctors on obscure committees advising state Medicaid programs receive free dinners and consulting contracts with the pharmaceutical companies. Speakers who don’t disclose their financial ties to the pharmaceutical companies are asked to testify about the companies’ drugs. State Medicaid officials are invited to attend all-inclusive conferences for free where they mingle with drug representatives.

Beyond that, drugmakers use other tactics to get their products paid for by the Medicaid programs: lobbying state lawmakers to achieve their goals or helping doctors fill out extra paperwork to get Medicaid to pay for the costlier drugs as Warner Chilcott did. The result is that Medicaid sometimes spends more than necessary and may pay for medicines inappropriate for patients.

The drug companies say they are not responsible for the problems. A spokesperson for PhRMA said: “As an industry, our priority is ensuring that patients have access to the medicines they need . . . . States should consider changes to Medicaid that are in line with the intended goal of ensuring robust access to medically necessary drugs.” Pharmaceutical companies have strong incentives to be included on states’ lists of approved drugs. Doctors are far more likely to prescribe an approved drug to Medicaid patients and may encourage other insurers to do the same. To gain a spot on the coveted lists, drug makers offer the states “supplemental rebates,” which are on top of other price concessions required by federal law. “The drug committee meetings where those list decisions are made are a frequent destination for drug company representatives — and those who benefit from their largesse.”

Across the country, drugmaker representatives and pharma-friendly clinicians with industry ties swarm these low-profile drug committees, a review of meeting minutes shows. Center for Public Integrity and NPR reporters saw similar dynamics play out this spring in meetings in Arizona, Washington, D.C., and Louisiana. The committees, usually known as pharmacy and therapeutics committees or drug utilization review boards, are typically made up of volunteer pharmacists and doctors.

Critics of the practice say when pharma companies target these committees, the states don’t get good deals. They also can make bad decisions for their patients. Three out of five doctors voting on state Medicaid decisions received perks from pharmaceutical companies. There are at least 38 states with doctors serving on their Medicaid drug committees who collected more than $1,000 from pharmaceutical companies while they served on the committees. Consider that while this amount may point to how money influences Medicaid decisions, a study in JAMA Internal Medicine, “Pharmaceutical Industry-Sponsored Meals and Physician Prescribing Patterns for Medicare Beneficiaries” found that when doctors get as little as a $20 lunch, they are more likely to prescribe the company’s drugs.

As compared with the receipt of no industry-sponsored meals, we found that receipt of a single industry-sponsored meal, with a mean value of less than $20, was associated with prescription of the promoted brand-name drug at significantly higher rates to Medicare beneficiaries. The differences persisted after controlling for prescribing volume and potential confounders such as physician specialty, practice setting, and demographic characteristics. Furthermore, the relationship was dose dependent, with additional meals and costlier meals associated with greater increases in prescribing of the promoted drug.

The NPR article told of a nonprofit organization, the American Drug Utilization Review Society (ADURS), whose mission is to provide a forum of leadership and support for its members. It hosted a free conference for Arizona state Medicaid officials in Scottsdale, where Michael Magnotti, an endocrinologist, gave a talk on diabetes. He was paid $1,545 for the talk by Sanofi-Aventis; and he received more than $108,000 in consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for that year. Sanofi S.A. is the world’s fifth-largest multinational pharmaceutical company. And it was one of the companies to receive a letter from Rep. Cummings.

A more disturbing ADURS conference took place in 2003 when Purdue Pharma helped to fund it. A speaker told his audience that addiction from the medical use of opioids was rare, and he then described a phenomenon called “pseudoaddiction.” A slideshow of the presentation (linked in the STAT article) said pseudoaddiction included “appropriate drug seeking behavior” such as demanding doses before they are scheduled. In support of his claims, he referenced a letter published in the New England Medical Journal back in 1980: “Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics.”

This article has been repeatedly misused by pharmaceutical companies (like Purdue) as they assert that the risk of addiction from the medical use of opioids is almost nil. The potential influence of pharmaceutical companies like Purdue on opioid prescribing and the opioid epidemic has received significant attention in the media. Currently 24 states and Puerto Rico have sued Purdue for downplaying or concealing the risks of its painkillers. See the book by Barry Meier, Pain Killer for more on this issue. Also see “Doublespeak in the Opioid Crisis,” Part 1 and Part 2 for more about the misuse of the 1980 article. See “Giving an Opioid Devil Its Due” for more on Purdue Pharma. This concern is now being looked at in the research literature.

A new study released on January 18, 2019 in JAMA Network Open suggested there may be a link between aggressive marketing, drug company money and overdose death rates. The researchers found that counties receiving pharmaceutical marketing of opioids to physicians subsequently experienced increased mortality rates. Commenting on the study, Science Alert said while the study did not demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship, it did suggest that frequent trust-building visits, like lunches sponsored by drug sales reps, did more to promote prescribing the company’s drugs than high-dollar payments to physicians. One of the researchers said: “What seems to matter most wasn’t the amount of money doctors were paid, it was the number of times they were paid.”

Our findings suggest that direct-to-physician opioid marketing may counter current national efforts to reduce the number of opioids prescribedand that policymakers might consider limits on these activities as part of a robust, evidence-based response to the opioid overdose epidemic in the United States.

While Pharma’s spending on lobbying and advertising to doctors (and consumers) continues to rise, so do the negative consequences. Pharma knows marketing has a tremendous potential to grow its profits. So spending on lobbying has increased alongside that of marketing to doctors and consumers. The public pays a price by permitting these activities to continue unhindered. Unchecked greed seems to have helped facilitate the opioid crisis. Hopefully the efforts of legislators like Elijah Cummings will make it out of their respective committees and into law. We need to stop the runaway Pharma gravy train.