Safety Concerns with Esketamine

It is approaching the three-year mark since the FDA approved Janssen’s Spravato (esketamine), in conjunction with an oral antidepressant to treat adults with treatment-resistant depression. The acting director of the Division of Psychiatry Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said at the time, “There has been a long-standing need for additional effective treatments for treatment-resistant depression, a serious and life-threatening condition.” Esketamine was later approved to treat adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts. Despite the approval, Janssen said it is not known if esketamine is “safe and effective for use in preventing suicide or in reducing suicidal thoughts.”

Joanna Moncrieff and Mark Horowitz originally expressed concern in “Esketamine for treatment resistant depression” that history was repeating itself, that “a known drug of abuse, associated with significant harm, with scant evidence of efficacy, is being submitted for licensing, without adequate long-term safety studies.” In their 2019 article, they said they were surprised to see an article in the BMJ endorsing esketamine, as they thought it had been approved on “flimsy evidence.” Only one of three trials of acute treatment was positive and “the difference between esketamine and placebo was not large.” Particularly when compared to the large placebo effect. They acknowledged that serious adverse effects could take time to come to light, and concluded their article with the following warning:

Leaving this crucial research until after the drug is licenced, as the FDA has done in the United States … puts the public at risk and sets depressed patients up as unwitting guinea pigs in a huge and unregulated pharmaceutical experiment.

Peter Gøtzsche et al thought the safety and efficacy of esketamine was exaggerated. They thought the available evidence found that esketamine was “more likely to harm than benefit patients with resistant depression.” They thought esketamine should not be used in clinical practice. “But only as an experimental drug in randomised trials of adequate length, with long-term follow up, and with patient relevant outcomes assessing both harms and benefits.”

Horowitz and Moncrieff have updated their previous analysis in “Esketamine: uncertain safety and efficacy data in depression.” By June 2021, six 4-week efficacy trials have been published, with only one reporting a statistically significant difference between placebo nasal spray and esketamine. The one trial finding a statistically significant effect of four points, was not clinically significant given the large effect size (15.8 points) in the placebo plus antidepressant section of the study. It was also less than the 6.5-point difference used by Janssen in their sample size calculation; and had no long-term efficacy data. “The time point of four weeks in all these studies means the data are rather uninformative, since treatment-resistant depression in usually treated for months or years.”

They noted how other national health service organizations such as NICE (National Institute for Health Care Excellence) have examined the same evidence as the FDA and did not approve the drug for treatment resistant depression. However, NICE has launched a second consultation on the use of esketamine for treatment resistant depression after receiving feedback that it could benefit some patients. The results of that consultation have not been released yet. Horowitz has been critical of NICE’s delay of their decision on Twitter, saying: “Janssen’s antidepressant might not be much good, but their marketing spin is second to none. Hats off. I wonder whether NICE is in the spin room as they have been persuaded to delay their decision on esketamine for 10 months.”

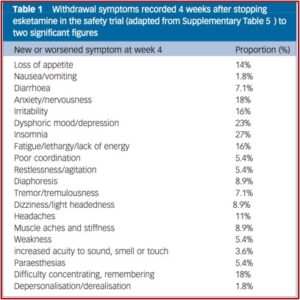

Horowitz and Moncrieff compiled a table (see below) of withdrawal symptoms 4 weeks after stopping esketamine. They acknowledged the table did not establish a causal attribution between the symptoms and stopping esketamine. The large numbers in the esketamine group and longer duration of treatment also may have inflated suicides in that group.

In the safety study, one in seven patients developed ‘treatment-emergent’ suicidal ideations and six attempted suicides occurred in a group “selected for not being actively suicidal.” Using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database, Gastaldon et al found a disproportionate number of suicides could be attributed to esketamine in the first year of its use in the USA. Their conclusion was, “Esketamine may carry a clear potential for serious AEs [adverse events], which deserves urgent clarification by means of further prospective studies.”

The doses of esketamine were similar to recreational doses of ketamine, which causes tolerance, dependence and withdrawal. The FDA and Janssen said withdrawal symptoms were probably not relevant in the relapse prevention study. Yet Janssen did not report data from the Physician Withdrawal Checklist to support this conclusion.

Although it is difficult to be definitive about the nature of experiences that occur following drug discontinuation, the possibility that withdrawal effects were mistaken for relapse requires consideration, as withdrawal effects overlap with most items on the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. NICE concluded that “any withdrawal effect would be difficult to distinguish from a change in depressive symptoms.”

The Janssen trial studies were also not representative of all individuals with major depression. They only included individuals who had failed two antidepressants (representing 44% of patients with depression). The studies excluded people with a recent history of suicidal intention, psychiatric comorbidity, drug and alcohol problems, vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS).

Another confounding effect in the efficacy with esketamine is the known fact that ketamine, like other anesthetics, cause a pleasurable ‘high’ for some users. It is not clear how this drug induced euphoria and the antidepressant effects can be distinguished. Horowitz and Moncrieff concluded that:

Overall, the central points of our Analysis remain: esketamine has a clinically uncertain effect at 4 weeks, and there are no studies with longer follow-up periods more relevant for the care of people with depression. The discontinuation trial potentially conflates relapse and withdrawal and there are concerning safety signals.

Successful suicides that occurred during the clinical trials were glossed over or presented as unrelated to esketamine. The FDA “Briefing Document” for the committee indicated there were three successful suicides; all were esketamine-treated subjects. After parsing the differences between the three cases, the Briefing Document said: “Given the small number of cases, the severity of the patients’ underlying illness, and the lack of a consistent pattern among these cases, it is difficult to consider these deaths as drug-related.” In “Nasal Spray for Depression? Not So Fast,” Kim Witzcak said: “In my opinion, we need more information on the potential link to suicide before an assumption can be made that it’s safe.”

The adverse events identified in the Briefing Document of the greatest concern were sedation, dissociation, and increased blood pressure; most of which occurred within the first two hours of administration. In order to minimize the risk of misuse and abuse of esketamine, the committee proposed following a Risk Evaluation Mitigation Strategies (REMS). The FDA can require REMS for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. “REMS are not designed to mitigate adverse events of a medication, rather, it focuses on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”

How did a drug with all of these concerns get approved by the FDA? There were exceptions made in the FDA approval process for esketamine as a “breakthrough therapy.” Witczak said the term treatment resistant depression (TRD) is the buzzword that allows drug companies to obtain FDA fast tracking:

Such designation gives the pharmaceutical company the ability to present smaller, fewer clinical trials in order to get their drug to market quicker. While most approved antidepressants currently on the market had to show effectiveness data from at least two positive short-term trials, Janssen only presented one positive short-term trial and the second is an incomplete picture as it is from a withdrawal trial. Janssen’s other trials failed to meet their primary endpoints for efficacy.

Janssen is persisting in its efforts to expand the market for Spravato/esketamine. It appears to me they convinced NICE to delay announcing their decision on esketamine for 10 months in order for the company to spin some additional information. And perhaps to convince NICE to reverse its rejection of esketamine. For more on esketamine, see: “Esketamine Craze,” “Hype and Concern with Esketamine,” “Evaluating the Risks With Esketamine,” and “Doublethink with Spravato?”