Two Trees in the Garden

Genesis two describes how God planted a garden in Eden and placed the man he had created (Adam) in it. Out of the ground God caused trees to grow, trees that were good for food and pleasant to see. Then the author of Genesis drew his readers attention to two particular trees in the middle of the garden—the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. What was so special about these trees?

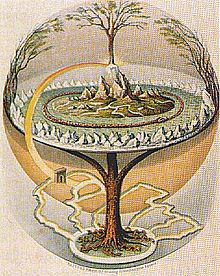

According to Ingrid Faro in the Lexham Bible Dictionary, the tree of life represents immortality, divine presence, wisdom and righteousness as a path of life; with an eschatological promise. It symbolizes the fullness of life and the immortality available in God. The opening and closing chapters of the Bible contain references to the tree of life. In chapter 22 of Revelations, trees of life grow on each side of the of the river of life and produce twelve kinds of fruit. The leaves of the trees are for the healing of the nations: “No longer will there be anything accursed” (Revelations 22:3). Note the plural of trees.

References to the tree of life and its symbolism appear throughout the Old Testament. In Genesis, the tree of life represents God’s life-giving presence in the garden of Eden and humanity’s ready access to Him.

The garden of Eden is God’s sanctuary and dwelling place. See “Nature, Red In Tooth & Claw, Part 2” for more on this point. Humans were placed in the garden to serve and protect it and to represent Him in the physical universe (Genesis 1:28).

In Proverbs, attaining wisdom is associated with the tree of life. Proverbs 3:18 says, “She [wisdom] is a tree of life to those who lay hold of her; those who hold her fast are called blessed.” Proverbs 11:30 says, “The fruit of the righteous is a tree of life.” It is also a fulfilled desire (Proverbs 13:12).

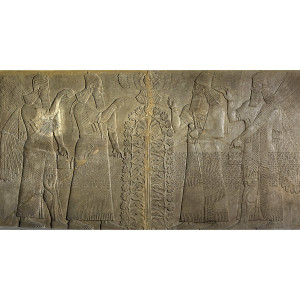

The golden candlestick in the tabernacle was a stylized tree of life, as is the menorah. The walls and the doors of Solomon’s temple, representing sacred space and God’s presence with humanity, contained images of trees and cherubim reminiscent of the garden of Eden. Ezekiel says sacred trees will be present in the future temple (Ezekiel 41:17-18). Ezekiel 47:12 recalls the garden of Eden in its description of a river, flowing from the temple with trees bearing fruit for food and leaves for healing on both sides. Revelations 22 draws on the imagery here in Ezekiel 47.

The ancient readers of Genesis would have understood the tree of life to be associated with eternal life. In the ancient Near East, a tree of life was a common theme representing humanity’s quest for immortality. In the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh discovers a plant that will restore whoever eats it to his youth. But a serpent stole the plant from him and swam away. The Lexham Bible Dictionary noted that in contrast to the Biblical account, the plant in the Epic of Gilgamesh rejuvenates, but does not offer immortality.

It thus differs from the tree in Genesis 3:22, whose fruit is said to enable the consumer to “live forever.” When Gilgamesh fails to attain the plant of life, he is encouraged to seek wisdom. In contrast, in the Bible, when Adam and Eve seek to gain illicit knowledge from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, they lose access to the perpetual life offered by the tree of life. In the Gilgamesh epic, the source of life is intended only for the gods, but in the biblical account the tree of life seems freely given to the humans.

In The Babylonian Genesis, Alexander Heidel described the Adapa Legend, one of the Babylonian creation stories found within the Amarna letters. Adapa was created by Ea, the Babylonian god of wisdom, to be the provisioner of Ea’s temple in the city of Eridu. He was destined to be a leader among men and Ea endowed him with wisdom and intelligence but not immortality. When immortality is offered to him by the sky god Anu, Ea tricked Adapa into refusing the gift, telling him it was the food and water of death. “By refusing the food and the water of life, Adapa not only missed immortality but also brought illness and disease upon man.”

Like the biblical account of the fall of man, the Adapa story wrestles with the questions: “Why must man suffer and die? Why does he not live forever?” But, unlike the biblical account, the answer it gives is not: “Because man has fallen from a state of moral perfection,” but rather: “because Adapa had the chance of gaining immortality for himself and for mankind, but he did not take it. The gift of eternal life was held out to him, but he refused the offer and thus failed of immortality and brought woe and misery upon man.” The problem of original sin does not even enter into consideration.

In contrast to the tree of life, Gordon Wenham said in his commentary on Genesis 1-15 that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is only found in the Genesis story of the fall of man. He said establishing its significance is then significantly more difficult, but necessary because it is a key phrase in the narrative. Wenham rejected understanding “knowing good and evil” as either moral discernment or simply a description of the consequences of obeying or disobeying the commandments given by God.

Understanding it as moral discernment, knowing the difference between right and wrong, cannot be taken seriously given the narrator’s assumptions. “It is absurd to suppose man was not always expected to exercise moral discretion or that he acquired such a capacity through eating the fruit.” Eve’s reply to the serpent in Genesis 3:2-3 indicates she already possessed a knowledge of right from wrong.

Wenham said understanding “knowing good and evil” to merely signify the consequences of obedience or disobedience was also inadequate. As noted in Genesis 3:5 and 3:22, eating of the tree “offered knowledge appropriate only to the divine.” Additionally, it does not fit with Deuteronomy 1:39 and 2 Samuel 19:36, “which observe that neither the very young nor the elderly know good and evil.”

The acquisition of wisdom is seen as one of the highest goals of the godly according to the Book of Proverbs. But the wisdom literature also makes it plain that there is a wisdom that is God’s sole preserve, which man should not aspire to attain (e.g., Job 15:7–9, 30; Proverbs 30:1–4), since a full understanding of God, the universe, and man’s place in it is ultimately beyond human comprehension. To pursue it without reference to revelation is to assert human autonomy, and to neglect the fear of the Lord which is the beginning of knowledge (Prov 1:7).

Wenham then referred to Malcom Clark’s observation that the phrase “good and evil” in legal contexts was used to describe legal responsibility. From this perspective, in Genesis 2-3 the phrase is used to signify moral autonomy, “deciding what is right without reference to God’s revealed will.” In the garden, God’s revealed will amounted to warning Adam and Eve to not seek knowledge of good and evil independent of His commandment on the pain of death. “In preferring human wisdom to divine law, Adam and Eve found death, not life” because they chose to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

With the two trees, Adam and Eve are presented with a choice between obeying the wisdom of God in the tree of life or seeking their own wisdom, autonomous from God in the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. As a result of their choice, they realized they were now naked (ʿêrōm) before God (3:7, 10, 11); guilty of disobeying Him. See “Nakedness in Genesis” for more on this distinction.