Fentanyl: Fraud and Fatality

In December of 2016, several former pharmaceutical executives and managers of Insys Therapeutics were arrested on charges they participated in a nationwide conspiracy to bribe medical practitioners to prescribe one of the company’s fentanyl products, Subsys. The medication is approved for treating cancer patients suffering intense episodes of breakthrough pain. “In exchange for bribes and kickbacks, the practitioners wrote large numbers of prescriptions for the patients, most of whom were not diagnosed with cancer.” The indictment also alleges that these same former Insys executives conspired to “mislead and defraud” health insurance companies who were reluctant to approve payment for Subsys when it was prescribed for non-cancer patients.

The Special Agent in Charge of the Boston Field Division of the FBI said top executive of Insys Therapeutics, Inc. allegedly paid kickbacks and committed fraud in selling the highly addictive opioid. “The indictment also alleges that the conspiracy to bribe practioners and to defraud insurers generated substantial profits for the defendants, their company, and for the co-conspirator practioners.” The investigative team included multiple federal agencies, including: FBI, FDA Office of Criminal Investigations; Health and Human Services (HHS), U.S. Postal Service, the Department of Labor, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reporting for STAT News on the indictments, David Armstrong said a Florida doctor was invited to Insys headquarters near Phoenix, where sales officials took him out for a night on the town. In a text message to a sales rep, one of the company’s regional sales managers said: “He had to have had one of the best nights of his life.” The next week the doctor wrote 17 prescriptions for Subsys, when he usually wrote three. “He also received $260,050 in payments over three years for participating in the Insys speaking program — something federal officials allege was nothing more than a mechanism for bribing doctors.”

Subsys was launched in March 2012 into a crowded field of competitors, which included other brand-name medications and several generics. The drug was approved only for cancer patients with intense flares of pain — a narrow market — and only about 2,000 doctors in the country prescribed fentanyl products. The drug is also expensive, costing thousands of dollars a month.

Prosecutors allege the company overcame these challenges with a speaker program, where “educating” doctors on the use of the drug was actually a way to bride them. A former chief executive of Insys wrote to sales managers that they needed to make it clear to sales reps how having one of their top targets as a speaker “can pay big dividends for them.” Doctors didn’t need to be good speakers; they just needed to “write a lot of” Subsys prescriptions. The indictment did not identify any of the parishioners by name who allegedly received and kickbacks.

To sweeten the pot, the Insys employees allegedly scheduled speaking events at establishments owned by doctors, or their families and friends. The events allegedly had little do with education: They were often held at high-priced restaurants and attendees were frequently just friends of the doctor hired as the speaker, the indictment alleges. Fake names were used on sign-in sheets, and some events had no attendees at all, according to prosecutors.

The cancer market for Subsys was considered to be “small potatoes” by one of the indicted former Insys executives. While the alleged bribes led doctors to prescribe more prescriptions for Subsys, insurance companies were reluctant to pay when the drug was prescribed for non-cancer patients. So a system was created to deceive insurers into paying for off-label uses of the drug, which is incidentally, quite expensive. A call center was created at Insys to handle insurance reimbursement approvals for doctors prescribing Subsys.

Employees in this unit are alleged to have contacted insurers, giving the appearance they were calling from the doctor’s office. Along with the supposedly deceptive medical information given to the insurers, they reportedly said patients had difficulty swallowing, which meant Subsys, as a nasal spray, had a distinct advantage over similar products that were in pill form. “Employees of the unit were rewarded with lucrative financial bonuses if the entire unit met a weekly target of reimbursement approvals.”

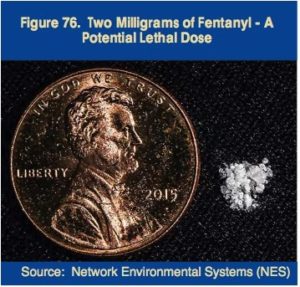

The Subsys fiasco is not the only fentanyl-related contribution to the opioid problem in the U.S. Two years ago the DEA issued a nationwide alert on fentanyl as a threat to health and public safety. State and local labs reported 3,344 fentanyl submissions in 2014, an increase from 942 in 2013. “In addition, the DEA has identified 15 other fentanyl-related compounds.” Warnings were issued to law enforcement about guarding against fentanyl absorption through the skin or accidental inhalation of airborne powder, as it is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin. Ingesting as small as .20 mg to 2mg of fentanyl can be lethal. The following image, taken from the 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA), illustrates the size of 2mg of fentanyl compared to a penny.

Globally, fentanyl abuse has increased in Russia, Ukraine, Sweden and Denmark. Mexican authorities have seized fentanyl labs run by the drug cartels. Intelligence indicated the precursor chemicals for fentanyl have come from companies in Mexico, Germany, Japan and China.

According to the 2016 NDTA, licit fentanyl is only diverted on a small scale. Illicit fentanyl, typically manufactured in China or possibly Mexico, is smuggled into the U.S. across the border with Mexico. Traffickers usually obtain fentanyl and mix it with heroin on their own. This happens at a variety of locations, including homes and even hotel rooms.

In August 2015, the DEA Manchester, New Hampshire DO, along with the Salem, New Hampshire Police Department, conducted an enforcement operation at a fentanyl mill in a hotel in New Hampshire. The traffickers used a hotel room kitchenette for mixing heroin and fentanyl together. Upon entry by law enforcement officers, the traffickers attempted to dispose of the drugs down the sink, spilling the highly lethal drugs all over the room.

Traffickers in the U.S. are also using fentanyl powder and a pill press to create counterfeit pills of oxycodone and other drugs. Officials in New Jersey and Tennessee seized pills that appeared to be oxycodone. But laboratory analysis indicated they were fentanyl or acetyl fentanyl. In May of 2015, Orange County Police Officers in California seized what appeared to be black tar heroin. “Upon laboratory analysis, the substance was revealed to be fentanyl and showed no traces of heroin or any other drug.”

In another article for STAT News, David Armstrong described the China connection with fentanyl. Raw fentanyl and the machinery necessary for assembly-line production of the drug are coming from Chinese suppliers. “The fentanyl pills are often disguised as other painkillers because those drugs fetch a higher price on the street, even though they are less potent, according to police.” A Southern California fentanyl lab had a dozen different packages shipped to mail centers and residences. A box labeled as a “Hole Puncher” was in fact a quarter-ton pill press. “The Southern California lab was just one of four dismantled by law enforcement in the United States and Canada in March [of 2016].”

In British Columbia, police raided a lab at a custom car business that was allegedly shipping 100,000 fentanyl pills a month to Calgary, Alberta. Federal agents shut down a Seattle lab set up in the bedroom of a home in a residential neighborhood. Police near Syracuse New York raided a similar residential lab, where they were warned by the people there not to touch the fentanyl without gloves because of its potency. “The emergence of decentralized drug labs using materials obtained from China — and often ordered over the Internet — makes it more difficult to combat the illicit use of the drug.” See “Buyer Beware Drugs” for more on this topic.

In January of 2017 the acting administrator of the DEA met with Chinese officials to address the synthetic drug crisis in the U.S. He said: “These meetings underscore our improving relationship and cooperative efforts as we work to stem the flow of dangerous synthetic opioids and related chemicals. I appreciate the good work they are doing in China to help us address our opioid epidemic.” The DEA maintains an office in Beijing and hopes to expand its presence in China. Hopefully, if the China connection with fentanyl is turned off, the future outlook from the 2016 NDTA will not be as bleak.

Fentanyl will remain an extremely dangerous public safety threat while the current production of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl continues. Fentanyl poses not only a threat to users, but also to law enforcement personnel and postal service employees as minute amounts of the drug are lethal and can be inadvertently inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Although many drug users avoid fentanyl, still others actively seek it out for its strong and intense high. In 2015 traffickers expanded the historical fentanyl markets as evidenced by a massive surge in the production of counterfeit tablets containing the drug, and manipulating it to appear as black tar heroin. The fentanyl market will continue to expand in the future as new fentanyl products attract additional users.

In February 2017, Time reported that China announced that carfentanyl (carfentanil) and three related synthetic opioids would be added to its list of controlled substances effective March 1, 2017. The DEA called China’s action a potential “game changer.” Russell Baer, a DEA special agent said: “It’s a substantial step in the fight against opioids here in the United States. . . We’re persuaded it will have a definite impact.” In October, the Associated Press identified 12 Chinese companies the offered carfentanyl for export. That same month China began evaluating whether to add it and three other fentanyls to its list of controlled substances. “Usually, the process can take nine months. This time, it took just four.”