Voyages on the Starship Ketamine

Image by ThankYouFantasyPictures from Pixabay

On October 10, 2023, the FDA issued a warning about the potential risks of compounded ketamine products for the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, OCD and PTSD. The concern seems to center on the at-home use of ketamine compounds from a multitude of online sources, dispensing oral formulations such as ketamine lozenges or tablets. Not only is ketamine not FDA approved for the treatment of any psychiatric disorder, it has known safety concerns such as abuse and misuse, increased blood pressure, slowed breathing and “psychiatric events.” The FDA said these compounds should only be used “under the care of a health care provider.”

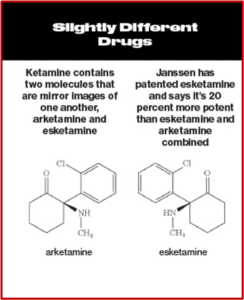

Ketamine is a Schedule III controlled substance approved by the FDA as an intravenous or intramuscular injection to induce and maintain general anesthesia. It is not FDA-approved to treat any psychiatric disorder. It is a mixture of two-mirror-image molecules, R-ketamine and S-ketamine—arketamine and esketamine, respectively. The “S” form of ketamine (esketamine), known as Spravato, was approved by the FDA as a nasal spray for the treatment of major depression and adults with acute suicidal ideation or behavior in 2019. See “Red Flags with Spravato,” “Doublethink with Spravato?,” “Repeating Past Mistakes with Esketamine” and other articles on this website expressing concerns with esketamine/Spravato.

Spravato is also a Schedule III controlled substance and like ketamine, and has similar risks of adverse events. This led the FDA to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) with esketamine, meaning that esketamine is required to be “dispensed and administered in medically supervised health care settings that are certified in the REMS and agree to monitor patients for a minimum of two hours following administration because of possible sedation and disassociation and the potential for misuse and abuse.” But ketamine and ketamine compounds can be legally prescribed off label to treat psychiatric disorders and do not have to have a FDA required REMS.

However, on February 16, 2022 the FDA published an alert describing the risks associated with the use of compounded ketamine nasal spray products. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting system (FAERS) and the medical literature identified five cases (reported between 2016 and 2021) of compounded ketamine nasal spray that resulted in psychiatric events “such as delusion, dissociation, visual hallucination, and panic attack as well as abuse and misuse.”

The reported concentrations of compounded ketamine nasal spray ranged from 125 – 200 mg/ml. Frequency of use varied from three sprays three times a day to six sprays eight times a day. The amount of medication administered to the patients with each spray is unknown. In most case reports, the patients self-administered the product at home, and it is unknown whether they were observed or monitored by a healthcare professional.

Because compounded ketamine nasal spray products are not FDA-approved, there is no FDA-approved dosing regimen for these products. There are also no data to support dosing conversion between Spravato (esketamine) nasal spray and compounded ketamine nasal spray.

The New York Times said the October 2023 alert sought to differentiate between the supervised use of ketamine as a therapy administered at clinics, and the “wellness centers” or online marketers that prescribe the drug via telemedicine so that buyers can take the drug at home. The alert included a caution that individuals receiving ketamine products from compounders and telemedicine platforms may not receive information about the potential risks associated with the product. “At-home administration of compounded ketamine presents additional risks because a health care provider is not available onsite to monitor for serious adverse outcomes resulting from sedation and dissociation.”

The pandemic-related boom in telehealth has given rise to a legion of online prescribers that dispense inexpensive ketamine lozenges, tablets or nasal sprays following a brief video interview. Some companies provide as many as 30 doses after one session, which experts say can lead to misuse.

Company executives in the compounding industry say they’d welcome government oversight. But they are concerned that a lack of flexibility in the FDA’s guidance could result in overly aggressive enforcement by state regulators. The manager of a compounding pharmacy in San Francisco said he is concerned these online sellers will ruin it for everyone. “Our fear is that regulators, if they perceive a threat to public health, will move to take this amazing medicine away and leave patients at risk.”

Psychiatric Times also expressed concerns with at-home ketamine therapy. They described a report by the All Points North Treatment Center in Edwards Colorado of 2,000 adults where 64% said they thought ketamine helped with their mental health symptoms. But 55% who tried at-home ketamine therapy also admitted accidentally or purposely using more than the recommended dose. The Editor in Chief of Psychiatric Times said, “Esketamine has to be administered in person by a trained health care provider. The use of at-home ketamine bypasses this safety net and puts individuals at risk, undermining the FDA’s REMS protocol to minimize risk and maximize safety and prevent diversion and abuse/misuse.”

There were reservations in 2019 with the approval process for esketamine, Spravato (see “Hype and Concern with Esketamine” and “Evaluating the Risks with Esketamine”). A NPR interview BEFORE the FDA approved esketamine predicted the problem the FDA is now attempting to address in its alert for “compounded ketamine products.” A doctor who prescribed ketamine to his patients said doctors would continue to offer a generic version of ketamine for depression because it would be cheaper than the cost of Spravato with its REMS. The generic form of ketamine was cheap, and could be taken at home with the assistance of a nasal spray, he said. “Any psychiatrist or physician can prescribe [it] without the restrictions that are going to be applied to esketamine.”

A Cunning Methodology

In a new study, Stanford researchers devised a cunning workaround to disguise the dissociative properties of ketamine. A major difficulty with doing clinical trials on psychedelic drugs like ketamine is the difficulty of providing a satisfactorily double blinded methodology. Participants can usually tell whether or not they were given ketamine or a placebo. The researchers “recruited 40 participants with moderate to severe depression who were scheduled for routine surgery, then administered a dose of ketamine or placebo when the participants were in surgery and under general anesthesia.”

They were surprised to find that both groups experienced the large improvement in depressive symptoms usually seen with ketamine. The senior author of the study he was surprised to see the result. He quoted some participants as saying their life was changed; they never felt like that before. “But they were in the placebo group.” Both the ketamine and placebo groups saw their depression rating scores drop by half and stayed roughly the same throughout the two-week follow-up of the study.

The researchers thought it was unlikely the surgeries and general anesthesia accounted for the improvement. They theorized the positive expectations of the participants played a key role in the effectiveness reported by them. “Those who had improved more in their depression scores were more likely to think they received ketamine, even when they didn’t, implying some preexisting positive expectations for ketamine.” The senior author said this was nothing new.

Placebo is probably the single most effective, consistent intervention in medicine, full stop. It’s seen in every trial, and we should probably be paying more attention to the factors that give rise to it.

However, he said the takeaway shouldn’t be that ketamine “is just a placebo.” He thought that was a disservice to placebos. He hypothesized there may be a physiological resonance between the placebo effect and how ketamine works. “There is most definitely a physiological mechanism, something that happens between your ears, when you instill hope.” He added that the results also suggest the psychedelic experience may not be crucial to the drug’s benefits, although it likely encourages more positive expectations.

Maybe with a non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analog you can get the same benefits without having to, you know, go to outer space.