Global Troubles with Tramadol

In the US, we see synthetic opioids like fentanyl grabbing headlines, and rightly so. The CDC reported the number of drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl increased from 1,663 in 2011 to 18,335 in 2016. The death rate more than doubled between 2013 and 2014, nearly doubled from 2014 to 2015 and more than doubled again from 2015 to 2016. Yet the World Drug Report 2019 said the non-medical use of tramadol required equally urgent attention, particularly in Africa. Global seizures of tramadol increased from 9 tons in 2013 to a record high of 125 tons in 2017. The largest quantity of tramadol seized from 2013 to 2017 was 96 tons by Nigeria, followed by Egypt with 12 tons. The main destinations were countries in West and Central Africa.

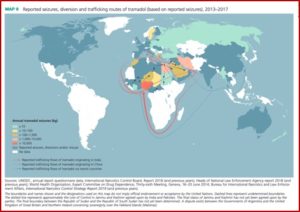

The fact that tramadol has been intercepted in areas close to where the Islamic State and some of its associated groups have been active has led to speculation that tramadol trafficking may be used to finance terrorist activities and used non-medically by their fighters to suppress pain and increase endurance. The largest tramadol seizures in Europe in recent years concerned shipments ultimately bound for North Africa, but they were modest in comparison to those intercepted by some countries in North Africa and the Middle East. “There have also been reports of non-medical use of tramadol in North America, Europe, East and South-East Asia, and Oceania, where diversion from licit sources has been reported in a number of countries.” See the following map.

Dr. Mahmoud Elhabiby reported the 2015 National Drug Survey in Egypt found that tramadol dependence (2.4%) ranked just behind cannabis (2.5%). “Moreover, the study show that Tramadol is the most prevalent opioid that causes dependence;” higher than heroin (.3%).

In Nigeria a cross sectional study where clients’ medical records were reviewed found the prevalence of tramadol abuse was 54.4% for the stipulated review period. In the original study, 67% of the subjects reported using multiple psychoactive substances, with benzodiazepines (44%) and cannabis (53%) being the most common. “Over 91% of the subjects obtained the drugs without a prescription and over 60% met at least three ICD-10 Diagnostic criteria of dependence.”

The CEO of Ghana’s FDA, Delese Mimi Darko, said “It is important we let people know that abusing medicines like Tramadol can have bad consequences, including death.” There have been reported cases of armed robbery, youth vandalism, car accidents, and in some cases, violence linked to the use of tramadol. The FDA in collaboration with the police seized over 500,000 capsules of tramadol in 2017. Given Ghana’s porous borders, tramadol abuse is a regional problem. Darko called for the development of a national tramadol abuse prevention strategy.

In December of 2017 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) warned the international community of the implications of the non-medical use of tramadol on the economies and security of West Africa. The UNODC Regional Representative, Pierre Lapaque, said “The rise of tramadol consumption and trafficking in the region is serious, worrying, and needs to be addressed as soon as possible. We cannot let the situation get any further out of control.” Reportedly tramadol is smuggled through the Gulf of Guinea by transnational organized crime networks, through areas partially controlled by armed groups and terrorist organizations.

By the end of September 2017, over 3 million tablets were seized in Niger, packed in boxes with the United Nations logo. In August of 2017, Cameroonian customs officials on the border of Nigeria seized 600,000 tablets intended for Boko Haram. In August of 2018, the UNODC organized a workshop to address the opioid problem in West Africa. “The event brought together senior representatives of law enforcement and health-care services, justice and law enforcement, as well as chiefs of the Inter-ministerial drug committees from Togo, Nigeria, Niger, Ghana, Benin and Côte d’Ivoire.”

The problem of abusive consumption and trafficking of tramadol plays a direct role in the destabilization of the region, as not only do groups smuggle tramadol across borders to generate revenues, they also use it for themselves. As stated by Mr. Lapaque, “Tramadol is regularly found in the pockets of suspects arrested for terrorism in the Sahel, or who have committed suicidal attacks. This raises the question of who provides the tablets to fighters from Boko Haram and Al Qaeda, including young boys and girls, preparing to commit suicide bombings”.

A study done of patients visiting pharmacies in northern Iran showed that 56% of patients who sought tramadol did not have a prescription. “More than 63% of patients reported a history of addiction or drug abuse.” The majority of people seeking tramadol were adolescents/young adults, under the age of 30. Fifty-five percent were under the age of 18. “More than 71% had been able to get access to tramadol without a prescription in the past.” And more than 71% had taken at least two courses of tramadol for more than a week in the past year.

Another study of Egyptian university students by Bassiony et al, “Opioid Use Disorders Attributed to Tramadol Among Egyptian University Students,” found the prevalence of tramadol use was 12.3% among university students. It was higher among males (20.2%) than females (2.4%). Only 15% were using tramadol alone. One-fifth of these students started with tramadol as their first drug. The average age at onset of tramadol use was 17.6 years of age. There was a considerable relationship between tramadol use and other substances. “Smoking, cannabis, and alcohol use predict tramadol use. About 60% of students who use tramadol had drug-related problems and 30% had dependence.”

A different study by Medhat Bassiony and others, “Adolescent tramadol use and abuse in Egypt,” stated tramadol abuse liability was underestimated and the evidence for abuse and dependence was emerging. Here the prevalence of tramadol use was 8.8% among school students, with the average age of onset of tramadol use was 16.5 years of age. Eighty-three percent reported using tramadol alone and the remaining 17% combined tramadol, alcohol and cannabis. Two-thirds of these students started with tramadol as their first drug after they started smoking tobacco. Over one-third of tramadol users had drug-related problems and 6% had drug dependency concerns. They recommended:

Large population-based longitudinal studies in adolescents and young adults are needed to estimate the prevalence, risk factors and consequences of tramadol use in Egypt. In addition, the possible role of tramadol as a gateway drug in the development of substance abuse and dependence in Egypt should be investigated.

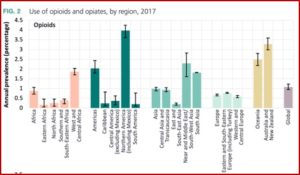

Returning to the global perspective, the World Drug Report 2019 estimated 53 million people used opioids at least once in the past year, of whom half were past-year users of opiates, heroin and opium. The highest prevalence of non-medical use of opioids was in North America, with 4% of the population between 15-66. This represented 25% of global opioid users. The major opioids of concern in North America were hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine and tramadol. The use of opioids in Australia and New Zealand was much higher (3.3% of the adult population) than the global average (just over 1%), with the non-medical use of opioids also being the main opioids of concern. See the following chart:

While America struggles with its own opioid crisis, across much of Africa and the Middle East tramadol is the drug of choice; a choice “fueled by cut-rate Indian exports and inaction by world narcotics regulators.” Unlike other opiates, tramadol isn’t regulated by the International Narcotics Control Board. So, it flows freely from factories in India and Egypt into Gaza, where the tramadol crisis started in the tunnels. Working grueling 12-hour shifts in the underground tunnel network, tramadol was freely exchanged between tunnel workers. “Bosses handed out pills before shifts to keep people moving amid the stresses and dangers.”

Tramadol was cheap. One pill cost just two shekels (56 cents). One 17-year old working in the tunnels was soon taking 8 pills daily. During the wars with Israel, he kept working. The bosses paid extra if he did, “so he self-medicated with tramadol as the bombs fell.” But then Egypt and Israel began flooding and bombing the tunnels and it was too dangerous to do tunnel work anymore. Now 23, he found himself unemployed and addicted to tramadol. However, the tramadol wasn’t the same quality as when he had started using, so he he needed more.

Doctor Khaled al-Safadi, who has worked in Gaza’s Psychiatric Hospital for 15 years, said: “The percent [of tramadol users] is rising because of the severe situation, the siege that we are in, the generation that has no income. . . It’s an escape from the world they are living in.” Last year he opened the first inpatient ward for treating drug addiction. Of the 12 beds on the ward, just two were filled. “Drug abusers are afraid to seek help because of social stigma and lack of trust in dealing with government institutions—combined with the government’s own inattention to these pressing issues.”

But tramadol keeps coming. Instead of coming through the tunnels, it is smuggled in smaller quantities in washing machines and gas canisters. The collapse of the tunnel trade and high use has pushed prices up. Ten years ago, 20 shekels paid for 10 tramadol pills; today that buys just one. “Even the one escape left to them, getting high, is now increasingly unattainable.”

Don’t believe the myth that tramadol is a non-addictive, non-opioid alternative. It is an opiate agonist, meaning it binds to the mu receptor and activates the receptor to produce a biological response, the same as does heroin. It has a significant potential for overdose or poisoning. In excessive doses, whether alone or in combination with other CNS depressants such as alcohol, it can result in drug-related death.

Tramadol can cause withdrawal symptoms, particularly if it has been used regularly over a long time period or in high doses. Withdrawal symptoms, particularly if you stop using it suddenly, may include restlessness, watering eyes, runny nose, nausea, sweating and muscle aches. Seizures are more likely to occur at the high doses of tramadol abuse. According to drugs.com,

Serious side effects including seizures and serotonin syndrome may also occur due to drug interactions. Examples of drug classes where this might occur include the serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, SNRIs), TCAs and MAO inhibitors (like phenelzine or linezolid) — all types of antidepressants. In fact, tramadol should never be used with an MAOI inhibitor or within 14 days of taking an MAOI. Taking tramadol with drugs that already have a seizure risk may worsen that risk.

Tramadol is a Schedule IV Controlled Substance, according to the DEA. It has an abuse potential and as an opiate agonist can cause fatal overdose and respiratory failure. Extended release tablets and capsules have been misused by splitting, breaking, crushing, chewing, snorting or injecting the dissolved products. This results in the uncontrolled delivery of the drug and can result in overdose and death.

A study published in the British Medical Journal sought to examine the risk of prolonged opiate use in patients receiving tramadol versus other short-acting opioids. Receiving tramadol was associated with a “6% increase in the risk of additional opioid use” relative to others receiving other short acting opioids. The researchers concluded people receiving tramadol after surgery had a somewhat higher risk of prolonged opioid use when compared to those receiving other short acting opioids. They suggested federal officials consider reclassifying tramadol and that providers use as much caution when prescribing tramadol as they do with other short acting opioids. For more information on tramadol, see “Trouble with Tramadol.”