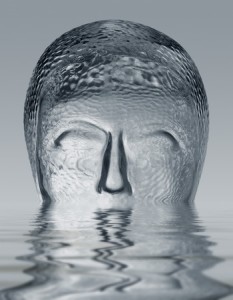

Hollow Man Syndrome

On her blog Joanna Moncrieff reflected on a memory she has of a young woman she encountered as a medical student in the 1980s who was confused and frightened when first brought to the hospital. She thought she was being watched and manipulated by evil forces. She believed there was something implanted in her body. Put on an antipsychotic, she became increasingly quiet as the dose was increased. But she also became emotionless, expressionless and physically sluggish. To Joanna, the woman seemed “empty and lifeless compared to what she had been before, although she was less distressed.” This was seen as making her ‘better.’

On her blog Joanna Moncrieff reflected on a memory she has of a young woman she encountered as a medical student in the 1980s who was confused and frightened when first brought to the hospital. She thought she was being watched and manipulated by evil forces. She believed there was something implanted in her body. Put on an antipsychotic, she became increasingly quiet as the dose was increased. But she also became emotionless, expressionless and physically sluggish. To Joanna, the woman seemed “empty and lifeless compared to what she had been before, although she was less distressed.” This was seen as making her ‘better.’

That reminded me of a young man I knew briefly around the same time who had a psychotic episode, triggered by his heavy use of marijuana. At least, that was his theory. My impression of him after his release from the hospital, where he also began using an antipsychotic, was that his personality had withered; he’d become a hollow man. A few years ago, I met briefly with someone trying to reclaim their thinking ability after taking lithium for over fifteen years. They wanted to cut back on the levels of lithium they were taking. We began working on that plan, but they kept getting caught up in a cognitive eddy of fear that they were going to lose their salvation. Was that psychosis or impaired thinking from the medication?

Another time I was concerned that after a first time manic episode an adolescent would remain on a maintenance dose of an antipsychotic for the rest of his/her life. Over time I convinced the family to transfer care to a psychiatrist willing to taper the teen off the antipsychotic. The person’s dose was initially halved and symptoms of mania emerged within ten to fourteen days of the initial taper. Was that a suppressed bipolar disorder emerging or was it a reaction to too steep an initial taper? The reaction was viewed by the family as a manifestation of the bipolar disorder that had been kept at bay by a low maintenance dose of the antipsychotic. They decided to stop counseling with me.

These and other experiences have led to the several articles I’ve written on the complications and dangers of antipsychotic medications. Reading the thoughts of psychiatrists like Joanna Moncrieff, Peter Breggin, and David Healy and others on Mad in America over the years had an effect as well. I appreciate the approach of Dr. Moncrieff, who said: “There are times when the use of antipsychotic drugs seems to produce just enough suppression that people can put aside their psychotic preoccupations, and re-establish a connection with the outside world.” Yet she can still see where “they produce an artificial state of neurological restriction,” like a chemical straightjacket.

In my view antipsychotic drugs can be useful in suppressing psychotic symptoms, and sometimes, when people are beset by these symptoms on a continual basis, life on long-term drug treatment, even with all its drawbacks, might be preferable to life without it. But most people who experience a psychotic breakdown recover. [Emphasis added] In this situation, antipsychotics are recommended not on the basis that they provide relief from severe symptoms, but because they are said to reduce the risk of relapse.

The Cochrane Collaboration published a review of antipsychotic maintenance treatment for schizophrenia in 2012. Their report was the first systematic review comparing the effects of all antipsychotic drugs to placebo for maintenance treatment. This is standard care after an acute phase of schizophrenia to prevent relapse. (And it seems, if a teenage manic episode is suspected of being a latent bipolar disorder) Not surprisingly, they found that antipsychotics were more efficacious than placebo in preventing relapse, especially at seven to 12 months. But they noted it was rare to find a study that did follow up longer than 12 months.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) since the 1950s have consistently shown that antipsychotic drugs effectively reduce relapses and need for hospitalisation. Conversely, they are, as a group, associated with a number of side effects such as movement disorders, weight gain and sedation.

Moncrieff pointed out two additional problems with these kinds of comparisons. First is the fact that they don’t compare people started on long-term medication treatment and people who were drug free in the placebo groups. Rather, the latter group consists of people who are withdrawn from long-term antipsychotics. Usually the taper or withdrawal occurs too quickly, precipitating discontinuation symptoms, like with the teen I described above. “The difference in relapse rates is almost certainly exaggerated in these studies, therefore, especially since relapse is often defined only in terms of a modest deterioration in general condition or symptoms.”

Another problem is there is typically little data in the studies on anything other than the so-called “relapse,” which is too loosely defined in most studies. So global functioning could be worse for people on continuous drug treatment than they would have been without it, even if they did experience a relapse. “Since the data has not been collected, we just don’t know.”

The first problem perpetuates a distorted message of how antipsychotic medications prevent relapse. The second problem means there is no information on whether someone might be better off if they didn’t use medication.

Moncrieff recently published an article in PLOS Medicine that called for a rethinking of antipsychotic maintenance: “Antipsychotic Maintenance Treatment: Time to Rethink?” Her summary points in the article were:

- Existing studies of long-term antipsychotic treatment for people with schizophrenia and related conditions are too short and have ignored the impact of discontinuation-related adverse effects.

- Recent evidence confirms that antipsychotics have a range of serious adverse effects, including reduction of brain volume.

- The first really long-term follow-up of a randomised trial found that patients with first-episode psychosis who had been allocated to a gradual antipsychotic reduction and discontinuation programme had better functioning at seven-year follow-up than those allocated to maintenance treatment, with no increase in relapse.

- Further studies with long-term follow-up and a range of outcomes should be conducted on alternatives to antipsychotic maintenance treatment for people with recurrent psychotic conditions.

She described a long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Wunderlink et al. in the Netherlands (in this article as well as in her blog) that confirms how long-term antipsychotic use will impair a person’s ability to function. The study also showed that when you gradually reduce people’s antipsychotics in a supportive manner, they are better off in the long-term.

This study should fundamentally change the way antipsychotics are used. These are not innocuous drugs, and people should be given the opportunity to see if they can manage without them, both during an acute psychotic episode and after recovery from one. If psychiatrists had not forgotten the lessons of the past, and if they had been prepared to acknowledge what they saw the drugs doing with their own eyes, this would have come about long ago.

The studies used to justify current clinical practice don’t provide reliable data on the pros and cons of long-term antipsychotic therapy. More research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of a gradual and individualized approach to antipsychotic discontinuation. Assessment of outcomes in addition to relapse is needed. Moncrieff recommended that while we await the results of further long-term discontinuation studies, that we reconsider antipsychotic maintenance treatment as the default strategy for people with recurrent psychotic disorders.

In “Psychiatric Drug-Induced Chronic Brain Impairment,” Peter Breggin described how chronic brain impairment (CBI) from chronic exposure to psychiatric drugs produces effects similar to those from a traumatic brain injury. He drew a parallel of effects between electroshock treatment, closed head injuries from repeated concussions (like what was portrayed in the movie, Concussion), and long exposure to psychiatric drugs:

The brain and its associated mental processes respond in a very similar fashion to injuries from causes as diverse as electroshock treatment closed head injury from repeated sports-induced concussions or TBI in wartime, chronic abuse of alcohol and street drugs, long-term exposure to psychiatric polydrug treatment, and long-term exposure to particular classes of psychiatric drugs including stimulants, benzodiazepines, lithium and antipsychotic drugs.

He said that by recognizing CBI, clinicians can enhance their ability to identify individuals who need to be withdrawn from long-term psychiatric drug treatment. Most patients show signs of recovery from CBI early in the withdrawal process. “Many patients, especially children and teenagers, will experience complete recovery.” With others, recovery could take place gradually; sometimes over years. Even when recovery is incomplete, Breggin said most patients wish to remain on reduced medication or none at all.

The symptoms of this syndrome include (1) Cognitive deficits, often first noticed as short-term memory dysfunction and impaired new learning, and difficulty with attention and concentration; (2) Apathy, indifference or an overall loss of enjoyment and interest in life activities; (3) Affective dysregulation, including emotional lability, loss of empathy and increased irritability; (4) Anosognosia or a lack of self-awareness about these changes in mental function and behavior.