Mistaken Beliefs About Addiction Relapse

The coroner’s report on Carrie Fisher’s death listed sleep apnea as the primary cause of death with drug intake as a contributing factor. In addition to the medications prescribed for her bipolar disorder (Abilify, Lamictal and Prozac), toxicology results found cocaine, methadone, heroin, oxycodone, and MDMA (ecstasy) in her system at the time of her death. Fisher’s family objected to a full autopsy, so the coronor’s conclusions were based on the toxicology results and an external examination of her body. “Based on the available toxicological information, we cannot establish the significance of the multiple substances that were detected in Ms. Fisher’s blood and tissue, with regard to the cause of death.”

The above information was from an article in Variety, but several media outlets were citing the coroner’s report and the same information. People said the coroner’s report indicated Ms. Fisher used cocaine sometime in the 72 hours prior to her death. During her 10-hour flight, she had multiple apneic episodes, which her personal assistant said was normal for her. Towards the end of the flight, she could not be roused. The report also noted she suffered from atherosclerotic heart disease, but then said: “The manner of death has been ruled undetermined.”

Although the official coroner’s report listed the manner of death as undetermined, it seems reasonable to assume from the toxicological information that Ms. Fisher had relapsed into active substance use. Billie Lourd, her daughter, said in a statement to People: “My mom battled drug addiction and mental illness her entire life. She ultimately died of it.” The cocktail of substances in Carrie Fisher’s system at the time of death, along with her history of heart disease, coupled with the increased risk of sudden cardiac death due to the medications used to treat her bipolar disorder lends credibility to Ms. Lourd’s statement.

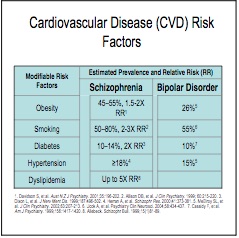

The use of psychiatric medication to treat her bipolar disorder may have been a contributing factor to Ms. Fisher’s heart failure. See the article, “Blind Spots with Antipsychotics” Part 1 and Part 2 for more on the health problems with antipsychotics. But the range of substances she used just before her death may also have been enough to precipitate a sudden cardiac death, particularly since she already suffered from heart disease. Struggling with a concurrent bipolar disorder and a substance use disorder is a double whammy to anyone in recovery. Instability with either issue is a serious risk factor for relapse. I knew of someone with a bipolar diagnosis and cocaine dependence. They bounced back-and-forth between active cocaine use and inpatient psychiatric treatment for depression ten times within a single year.

Ms. Lourd said her mother would want her death to encourage people to be open about their struggles, and to seek help for them. Historically, Carrie Fisher talked openly about her proneness to relapse. She told People in 1987: “I couldn’t stop, or stay stopped. It was never my fantasy to have a drug problem.” She would stop for a couple of months and then celebrate her abstinence by using again. “I got into trouble each time. I hated myself. I just beat myself up. It was very painful.” With that in mind, let’s assume the immediate cause for her untimely death was due to an apparent relapse into active drug use, and then discuss some mistaken beliefs about addiction relapse.

Terrance Gorski is a leading expert on addiction relapse prevention. He’s written several books on the subject, many of which are available through Herald House Independence Press at relapse.org. He also has a blog, Terry Gorski’s Blog, where he has made a significant amount of his material available for free. Here we’ll concentrate on his article, “Relapse Does not Mean Failure?”

Gorski said there were three mistaken beliefs that often interfered with helping relapse prone individuals. They are: (1) Relapse is self-inflicted; (2) Relapse is an indication the person is a failure who doesn’t want to recover; and (3) Once relapse occurs the patient will never recover.

In most cases, relapse is not self-inflicted. There isn’t a fully conscious, willful decision to throw over abstinence and return to active drinking or drug use. Relapse-prone individuals “experience a gradual progression of symptoms in sobriety that create so much pain that they become unable to function in sobriety. They turn to addictive use to self-medicate the pain.” They can learn to stay sober by recognizing these symptoms as early relapse warning signs. Next is identifying the self-defeating thoughts, feelings and actions used to cope with the symptoms and then learn more effective coping mechanisms, more healthy ways of responding to them.

Unfortunately, most relapse-prone patients never receive relapse prevention therapy, either because treatment centers don’t provide it or their insurance or managed care provider won’t pay for it.

Relapse is not automatically a sign that treatment has failed or the person really doesn’t want to recover. It is more likely that the root-cause of the person’s problems wasn’t addressed by the “standard package of treatment offered.” If this is the case, the risk of relapse increases dramatically. Learning to recognize relapse warning signs and how to cope with them would minimize this risk.

Gorski said that between one half and two-thirds of all individuals treated for alcohol and drug use problems will relapse. At least one half of those who relapse will establish long-term recovery within five to seven years of their first treatment experience. Believing that relapse means both the person and the treatment failed ignores the reality that for many, recovery involves a series of relapse episodes. “Each relapse, if properly dealt with in a subsequent treatment, can become the a learning experience which makes the patient less likely to relapse in the future.”

Chemically dependent people can be grouped into three types based upon their recovery and relapse histories. The first type is recovery prone and maintains total abstinence from their first serious attempt at change. Another type is relapse prone, with a series of short-term, low consequence relapse episodes before finding long-term abstinence. The third type is chronically relapse prone, who can’t seem to find long-term sobriety regardless of what they do.

Recovery prone individuals tend to be dependent on a single drug. They also have higher levels of social and economic stability. They may have steady employment, friendships and stable living situations. And they don’t have coexisting mental health issues, as Carrie Fisher did, or physical health issues, like chronic pain problems. These “garden variety addicts” have chemical addictions with few additional serious personal or social problems.

The second type of transitionally relapse-prone individuals, seem to have more severe addictions that are complicated by other problems. However, they learn from each relapse episode and take steps to modify their recovery programs to avoid future relapses. For example, they may downplay the risks of going around good friends who still drink or use drugs until they find themselves actively drinking or drugging again. Afterwards, they set and keep boundaries with those friends that better support their recovery.

The third type— chronically relapse-prone individuals—not only have the primary addiction for which they are being treated, but also a combination of the following coexisting issues. They may have multiple drug addictions, especially with opiates and methamphetamines. They can have an undiagnosed physical condition, a personality disorder or other mental health problem. There could be issues with severe post acute withdrawal (PAW), which becomes even more severe when the person is under high levels of stress.

Many relapse-prone patients fail to recover because these coexisting [issues] are not properly diagnosed and treated and they interfere with the primary treatment being given.

The third mistaken belief sees recovery as an all-or-nothing process—you either have it or you don’t. And if you relapse, you just don’t want recovery bad enough. Actually, recovery is a learned skill, acquired mostly by trial and error. Rarely does someone with long-term recovery get there without one or more short series of relapse episodes. “They learned from these experiences and figured out how to put together a meaningful and comfortable long-term recovery.”

So when you think about Carrie Fisher’s toxicology report, don’t assume she threw away her sobriety like it was an old, worn out Alderaan gown. Her relapse was likely the result of a gradual progression of symptoms occurring in her life. In time, they created so much pain in sobriety that she wasn’t able to function. So she tried to self-medicate. She also wasn’t a failure who didn’t want to recover. The openness in her life about her struggles with addiction and mental health belie such an assessment.

Like thousands of others each year, she died with multiple psychoactive substances in her system. But that doesn’t mean she would have never made it back to abstinence. Remember, she was Princess Leia; and Leia Organa never gave in to the tyranny of the Empire. Carrie Fisher would never have given up fighting against her addiction and mental health demons.

I have read and used Terence Gorski’s material on relapse and recovery for most of my career as an addictions counselor. I’ve read several of his books and booklets; and I’ve completed many of his online training courses. He has a blog, “Terry Gorski’s Blog”, where he graciously shares much of what he has learned, researched and written over the years. This is one of a series of articles based upon the material available on his blog and website.