Continue to Keep Marijuana Medical in PA

Medical marijuana has been available in Pennsylvania since February of 2018. Fortunately, progress to the legalization of recreational marijuana has not occurred yet. I’ve been urging for almost six years that we wait for the research into the risks and benefits of marijuana use can be reliably researched. Here are three recently published research articles to reflect on that suggest going ‘full Colorado’ in Pennsylvania may not be a good idea.

In August of 2023, The British Medical Journal (BMJ) published “Balancing risks and benefits of cannabis use” by Solmi et al. Their research was an umbrella review of 101 meta-analyses that have reported on the safety of cannabis, cannabinoids or cannabis-based medicines. According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study, Solmi et al said more than 23.8 million people have cannabis use disorder (CUD). In the U.S., the prevalence of CUD was estimated at around 6.3% in a lifetime. In Europe, around 15% of people aged 15 to 35 reported using cannabis in the past year.

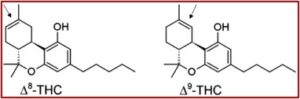

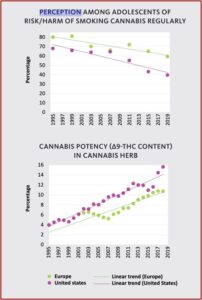

In Europe, over the past decade, self-reported use of cannabis within the past month has increased by almost 25% in people aged 15-34 years, and more than 80% in people who are 55-64 years. Cannabis or products containing tetrahydrocannabinol (cannabinoids) are widely available and have increasingly high tetrahydrocannabinol content. For instance, in Europe, tetrahydrocannabinol content increased from 6.9% to 10.6% from 2010 to 2019. Evidence has suggested that cannabis may be harmful, for mental and physical health, as well as driving safety, across observational studies but also in experimental settings. Conversely, more than a decade ago, cannabidiol was proposed as a candidate drug for the treatment of neurological disorders such as treatment-resistant childhood epilepsy. Furthermore, it has been proposed that this substance might be useful for anxiety and sleep disorders, and even as an adjuvant treatment for psychosis. Moreover, cannabis-based medications (ie, medications that contain cannabis components) have been investigated as putative treatments for several different conditions and symptoms.

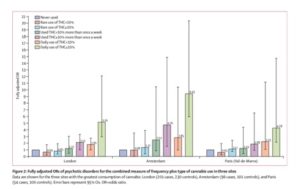

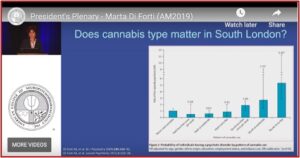

There was converging evidence of an increased risk of psychosis in adolescents and adults, and with psychosis relapse in people with a psychotic disorder. There was an association between cannabis and general psychiatric symptoms such as depression and mania; and detrimental effects on memory, verbal delayed recall, verbal learning and visual immediate recall. “Across different clinical and non-clinical populations, observational evidence suggests an association between cannabis use and motor vehicle accidents.” There was also evidence of an association with somnolence (drowsiness) with cannabinoids and cannabidiol. Cannabis-based medicines were associated with visual impairment, disorientation, dizziness, sedation and vertigo.

In addition to the association of cannabis and psychosis, cannabis use is associated with a worse outcome after onset, including poorer cognition, lower adherence to antipsychotics and a higher risk of relapse. “In other words, use of cannabis when no psychotic disorder has already occurred increases the risk of its onset, and using cannabis after its onset, worsens clinical outcomes.” Mood disorders have their peak of onset close to that for cannabis use, raising concern because of the associations noted in this study between cannabis and depression, mania and suicide attempt. High THC content cannabis is thought to serve at a gateway to other substances, especially in younger people.

With regard to the therapeutic potential of cannabis-based medicines, cannabidiol was beneficial in reducing seizures in certain forms of epilepsy. They were also beneficial for pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis, as well as for chronic pain in various conditions. In patients with chronic pain, the effects of prolonged use of cannabinoids needs to be tested “because current findings only come from short term randomized controlled trials.” Active comparisons between cannabidiol and available options for epilepsy, cannabis-based medicines and other pain medications, other treatments for muscle spasticity in multiple sclerosis are needed with a focus on efficacy and safety to inform future guidelines.

In conclusion, Solmi et al said converging and convincing evidence supported the association of marijuana use with poor mental health and cognition and the increased risk of car crashes. Cannabis use should be avoided in adolescents and young adults when neurodevelopment is still occurring, when mental health disorders begin and cognition is important for optimizing academic performance and learning. Cannabidiol could be considered as a potential treatment option in epilepsy. Cannabis-based medicines could be considered for chronic pain across different conditions, and for nausea and vomiting and for sleep in cancer.

Law and public health policy makers and researchers should consider this evidence synthesis when making policy decisions on cannabinoids use regulation, and when planning a future epidemiological or experimental research agenda, with particular attention to the tetrahydrocannabinol content of cannabinoids. Future guidelines are needed to translate current findings into clinical practice.

The 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) released in November of 2023, 22% of people 12 or older reported using marijuana in various ways (smoking, vaping, dabbing, eating or drinking, lotion or cream, taking pills or some other way). The percentage was highest among young adults, 18 to 25 (38.2% or 13.3 million people), followed by adults over 26 (20.6%, 45.7 million people), then adolescents 12 to 17 (11.5%, 2.9 million people). Among people 12 or older in 2022, 6.7% or 19 million people, has a CUD (cannabis use disorder) in the past year. The percentage of young adults 18 to 25 with CUD was 16.5% or 5.7 million people. Adolescents aged 12 to 17 with CUD was 5.1%, or 1.3 million people. These figures were higher than the data reported in the following article, “Cannabis-Related Disorders and toxic Effects,” perhaps reflecting more recent data.

In December on 2023, The New England Journal of Medicine published “Cannabis-Related Disorders and Toxic Effects” by Daniel Gorelick. The article reviewed the seven cannabis-related disorders defined in the DSM-5-TR. The author said worldwide, an estimated 209 million persons between 15 and 64 used cannabis in 2020. In the U.S., an estimated 52.4 million people 12 and older used cannabis in 2021, representing 18.7% of that age group. And 16.2 million persons met the diagnostic criteria for CUD.

Cannabis use disorder occurs in all age groups but is primarily a disease of young adults. The median age at onset is 22 years (interquartile range, 19 to 29). In the United States, the percentage of 18-to-25-year-old persons with current (past-year) cannabis use disorder in 2021 was 14.4%. Younger age at initiation of cannabis use is associated with faster development of cannabis use disorder and more severe cannabis use disorder.

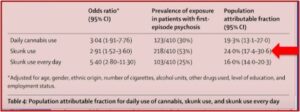

The major risk factors for developing CUD are the frequency and duration of cannabis use. And the core feature is loss of control, reflected in persistent use despite adverse consequences. The potency and amount of cannabis are also risk factors, but they have not been well studied because of the difficulty in quantifying the amount and potency of the THC content of products. “The potency of cannabis has doubled over the past 2 decades, according to analyses of samples seized by U.S. law enforcement, which may contribute to the increased risk of cannabis use disorder and cannabis-induced psychosis.” The risk of CUD increases with the frequency of use: 3.5% prevalence of CUD with yearly use (less than 12 days per year); 8.0% with monthly use (up to 4 days per month); 16.8% with weekly use (up to 5 days per week); and 36% with daily or near daily use.

Several clinical and sociodemographic factors are associated with an increased risk of cannabis use disorder, including the use of other psychoactive substances such as alcohol and tobacco; having had adverse childhood experiences (such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse); having a history of a psychiatric disorder or conduct problems as a child or adolescent; depressed mood, anxiety, or abnormal regulation of negative mood; stressful life events (such as job loss, financial difficulties, and divorce); and parental cannabis use. These significant associations do not necessarily indicate a direct causal influence on cannabis use disorder, because many of these factors are also highly associated with both cannabis use and frequent cannabis use.

Gorelick told Medical Xpress almost 50% of people with CUD have another diagnosable psychiatric disorder such as major depression, PTSD or generalized anxiety disorder. He said: “There is a lot of misinformation in the public sphere about cannabis and its effects on psychological health with many assuming that this drug is safe to use with no side effects.” About 1 in 10 people who use cannabis will become addicted and if you start using before the age of 18 the risk rises to one in six. Cannabis use accounts for 10% of all drug-related emergency room visits and is associated with a 30 to 40 percent increased risk of car accidents.

He concluded that CUD and heavy or long-term cannabis use have clear adverse effects on physical and psychological health. He thought research on the endocannabinoid system is needed to better explain the pathophysiology of these effects and to develop treatments. In other words, continue to keep marijuana medical in PA until we have reliable research to determine whether or not recreational marijuana should be legalized. So far, it’s not looking to be a wise move.

For more information on marijuana and the concerns with legalization, search for “marijuana” or “cannabis” on this website or see, PREPARING to Legalize Cannabis.” For more information on marijuana legalization in Pennsylvania, see “Keep Marijuana Medical in PA,” “Waiting Before Pennsylvania Goes ‘Full Colorado’” and others.