America’s Pentecost

About thirty miles northeast of Lexington Kentucky is the Cane Ridge Meeting House. It sits on the site of what historian Paul Conklin said was “the clearest approximation of an American Pentecost.” From August 6th through August 12th in 1801 thousands of people gathered to celebrate the Lord’s Supper. “It arguably remains the most important religious gathering in all of American history, both for what it symbolized and for the effects that flowed from it.”

The events in Cane Ridge were initially organized as a traditional Scottish and Ulster Presbyterian communion service. Communicants were carefully screened by the presiding ministers, and when approved, given a small lead token to admit them to the communion table. The bread and wine were served as the communicants sat at long tables. If the assembly was large enough, the communion tables were filled repeatedly, with the service continuing until sunset.

The minister described the origins and purposes of the sacrament, blessed the elements, and then took a seat at the head of the table. Those assembled at the tables passed and partook of the bread and wine. They would eat and drink quantities that approximated those of a real meal, and not just consume a mere token amount of bread and wine. After a corporate prayer, they returned to their seats.

Over time, the communion service was expanded into a three to five day affair. There was a day of self-examination with fasting and prayer; Friday and Saturday sermons; and the Sunday communion service. A follow-up thanksgiving service on Monday was common. The preaching and exhortation was more like later revivals, quite different than that of the weekly pastoral sermon. The emotion tenor made it a likely time for conversion. The great communions also became a kind of festival or fair, with thousands of noncommunicant individuals attending. The crowds of spectators required most of the preaching to be outdoors on canopied platforms—tents.

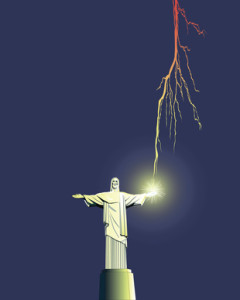

Many of the wilder bodily effects that occurred at Cambuslang Scotland and later at Cane Ridge first occurred in 1625 at a series of services in Ulster Ireland in that have come to be known as the Six Mile Water Revival. In Cane Ridge, Conklin noted how it was the Ulster communions that first reported people fainting dead away and being carried outside in a trance. “By the 1740s almost all the exercises that Cane Ridge would make famous, including not only sobbing, shouting, and swooning but bodily convulsions or jerks, had erupted in one or more congregations.” Similar revivals were occurring in Scotland, with Cambuslang being the penultimate example (See “Swift as Lightning”).

In Scotland and Ulster, as later in America, these huge regional communions proved very divisive. The extended communion normally functioned as a routine ritual that was loved by almost all Scottish Presbyterians. . . . But in the three or four waves of revival, the huge rural gatherings, with all the extreme physical exercises, dismayed or frightened possibly a majority of Presbyterian clergymen.

By the mid-eighteenth century criticism of the spectacle at these communion services was taking place. This centered on the spectators who remained on the fringes of the religious services. Some came for fun or socializing, some to observe or ridicule, some to exploit the occasion by marketing goods. Their behavior was largely uncontrollable, despite carefully developed rules. To this crowd, communion was a carnival. Some critics saw the services as an embarrassing throw back to medieval fairs. The Scottish poet, Robert Burns, wrote satirically of these communions in his poem: “The Holy Fair.” But devout Presbyterians held the yearly communion season to be the peak religious experience of the year.

Conklin observed that the Scots-Irish Presbyterians, with their custom of communion seasons described above, were the most suitable institutional setting for periodic revivals in America. Fittingly then, the area around Cane Ridge was settled by a group of Scots-Irish Presbyterians in 1790, who built the meeting house in 1791. In Logan County, over two hundred miles to the south and west of Cane Ridge, James McGready accepted a call as the minister to three small congregations in 1796. As soon as he arrived, he began preparing his congregations for a revival. He stressed an experiential religion and recommended a day of prayer and fasting each month. He also made use of the traditional four-day Scottish communion service. He timed the communions so that members of the three widely scattered congregations he pastored (named after local rivers: Red, Muddy, and Gasper) could travel to each of the other services, “thus creating the critical mass of people needed for a fervent revival.”

By the spring of 1797, he noted a brief awakening at Gasper River. By the summer of 1800, the Gasper River communion service drew people from distances as much as a hundred miles away. At the opening Friday session, there were already twenty to thirty wagons, with provisions, encamped nearby the meetinghouse. “The number of wagons on the grounds at Gasper River, and the informal tents created around some of the wagons, also gave Gasper River a disputed but pervasive claim to being the first camp meeting in America.” But according to McGready, the final sacrament at Muddy River exceeded that at Gasper River.

Revivals of various types “seemed to be popping up not only all over Kentucky but all over the United States in 1801.” Beginning in early May near the Licking River in northeastern Kentucky, there were a series of communion services leading up to the Cane Ridge service. Barton Stone, the minister of the Cane Ridge church, traveled to several of these, inviting those in attendance to come to his Cane Ridge communion beginning on Friday, August 6th. There had been anticipation for weeks before the service that Cane Ridge would not be “an ordinary summer sacrament.”

Services began on Friday, but rain held back the crowds. By Saturday, the roads were jammed with people traveling to Cane Ridge. The Saturday morning services were “reasonably quiet,” but by the afternoon, the preaching was continual, from both the meetinghouse and the tent. The excitement built, and before dark the noise from the cries and shouts of the penitent, mixed with the screaming of children and crying of babies and the neighing of horses led one visitor to refer to it as the roar of Niagra. “People could hear it as great distances.”

Although only ministers preached prepared sermons, or had allocated times to perform, literally hundreds of people served as exhorters at Cane Ridge. In the tumult the distinction between prepared sermons (with a theme or a text taken from the Bible and carefully developed points or arguments) and more spontaneous exhortations (extemporaneous or even impromptu practical advice, or tearful appeals or warnings) dissolved, particularly when outlying members of the audience could not even hear the sermons.

Some estimates have 20,000 to 30,000 people of all ages coming to the grounds around the Cane Ridge Meeting House on Saturday the 7th or Sunday the 8th of August. Conklin suggested that a more likely and more accurate estimate, mostly for logistical reasons, was there were at most 10,000 people on the grounds at one time. But he did acknowledge there could have been 20,000 at Cane Ridge at some point during the communion weekend and the following six days.

The majority of people at Cane Ridge were casual visitors or outsiders—those who came for the spectacle of the event. However, Conklin said this does not mean that all but a small minority was unresponsive to the religious content of the services. Many came to hear the preaching of able ministers besides observe the event and join in the excitement. While the communion service was orderly enough, the wildest exercises occurred outside the meetinghouse. Conklin said:

Outside, the groaning and falling continued. Some people experienced only weakened knees or a light head. . . . Others fell but remained conscious or talkative; a few fell into a deep coma, with the symptoms of a grand mal seizure or a type of hysteria. Crowds gathered around each person who swooned. Estimates of the number slain rose by Tuesday to 3,000, surely an exaggeration (more modest estimates ranged from 300 to 1,000).

A letter from a minister who was at Cane Ridge described the scene as follows:

Sinners dropping on every hand, shrieking, groaning, crying for mercy, convoluted; professors [of religion] praying, agonizing, fainting, falling down in distress, for sinners, or in raptures of joy! Some singing, some shouting, clapping their hands, hugging and even kissing, laughing; others talking to the distressed, to one another, or to opposers to the work, and all this at once—no spectacle can excite a stronger sensation.

Two ministers who went afterwards to assess the legitimacy of the revival in Kentucky and at Cane Ridge, Samuel McCorkle and George Baxter, had a sense that the extreme physical effects were incidental to what happened spiritually. Baxter has seen them in other revivals. However, McCorkle saw it was easier to be skeptical at a distance, as his own son was struck down in one of the meetings. While he was persuaded there could be a spiritual component to the extreme physical effects, McCorkle discounted the religious significance of the more violent exercises. “Sinners and saints were both susceptible.” McCorkle thought it was irresponsible for ministers to incite such exercises, since they were incidental to religious life.

Such “physical exercises” have occurred periodically within times of Christian revival before Cane Ridge and afterwards. The Cambuslang revival of 1742 and the Azusa Street Revival beginning on April 9, 1906 are two examples of physical exercises associated with times of revival. But the true test of a revival is not in the physical effects that occurred, but in the changed lives afterwards. George Baxter wrote to a fellow minister on January 1, 1802 that where Kentucky had been previously known for its debauchery, “I found Kentucky the most moral place I have ever been in.” Among the after effects of the Western revival, David Rice observed:

A considerable number of individuals appear to me to be greatly reformed in their morals. This is undoubtedly the case within the sphere of my particular acquaintance. Yea, some neighborhoods, noted for their vicious and profligate manners, are now as much noted for their piety and good order. Drunkards, profane swearers, liars, quarrelsome persons, etc., are remarkably reformed.

Ian Murray’s evaluation of the Kentucky revival in his book Revival and Revivalism noted parallels to Jonathan Edwards’ discussion of the Great Awakening. All awakenings are begun with the return of a profound conviction of sin. Many are brought from attitudes of indifference and cold formality to concern and distress so suddenly, that a temporary physical collapse could occur. By its very nature, a revival is bound to be accompanied by emotional excitement. Yet its progress, along with its abiding fruit and purity, is directly related to how such excitement is handled by its leaders.

When the degree of the Spirit’s work is measured by emotional strength, or when physical effects of any kind are considered proof of God’s action, fanaticism will follow. And those who adopt such beliefs suppose that any check on emotion or physical phenomena is equivalent to opposing the Holy Spirit. Murray concluded that the awakening in Kentucky was accompanied by the “chaff” of hysteria. He quoted Archibald Alexander of Princeton Seminary as saying:

It is not doubted, however, that the Spirit of God was really poured out, and that many sincere converts were made, especially in the commencement of the revival; but too much stress was laid on the bodily affections, which accompanied the work, as though these were supernatural phenomena, intended to arouse the attention of a careless world.