Xanax Is Not the Way Out of Anxiety

In November of 2022 Maria Shriver and her daughter Christina Schwarzenegger released a documentary on Netflix titled, Take Your Pills: Xanax. Their film looked at both the cure and curse Xanax has become for so many people. In their interview Maria said we are in the midst of widespread anxiety for which people want a quick fix. Now individuals are asking, “What is the effect of taking this pill on my brain, or on my body?” What impact might this have if I want to stop taking Xanax down the road?

Xanax was originally approved by the FDA as in 1981 to treat anxiety associated with depression. The patent expired in September of 1993. On January 17, 2003 the FDA approved Xanax XR, an extended-release form, to treat panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. The patent for Xanax XR will expire on April 8, 2028. FDA Approved Labeling for Xanax-XR says its longer-term efficacy has not been systematically evaluated. “Thus, the physician who elects to use this drug for periods longer than 8 weeks should periodically reassess the usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.”

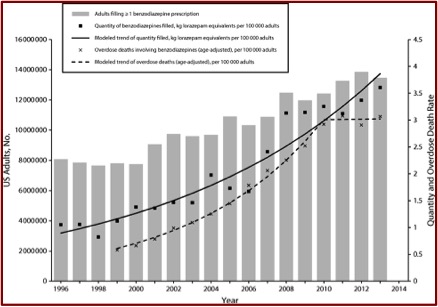

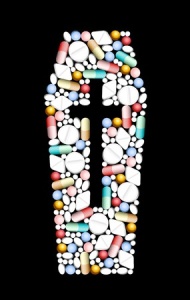

Xanax, alprazolam, is the most widely prescribed benzodiazepine on the market today. PsychCentral said it was the nineth most prescribed psychiatric medication with 16.78 million prescriptions in 2020. “A Review of Alprazolam Use, Misuse, and Withdrawal” said its clinical use has become a point of contention as addiction specialists consider it to be highly addictive, while primary care doctors prescribe it for much longer time periods than recommended. And it has been shown to have a more severe withdrawal syndrome than other benzodiazepines, “even when tapered according to manufacturer guidelines.” Data on national emergency department (ED) visits indicated alprazolam is the 2nd most common prescription medication and the most common benzodiazepine involved in ED visits related to drug misuse.

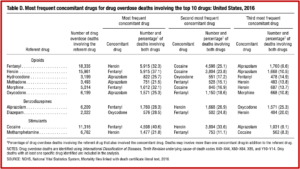

Alprazolam has a high misuse liability, particularly when prescribed to individuals with a history of some type of substance use disorder. Individuals with a history of alcohol or opiate use seem to prefer it to other benzodiazepines like Serax (oxazepam) because they found it to be more rewarding. CDC prescription death rate data indicated alprazolam was used with another drug over 96% of the time, usually with fentanyl. Heroin was the second most frequent concomitant drug. See Table D taken from the CDC report.

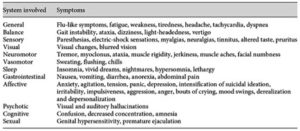

The above cited review of alprazolam said, “All benzodiazepines carry a risk of misuse, diversion tolerance and physical dependence.” Withdrawal symptoms seem to be more severe with Xanax because of its shorter half-life and high potency causing severe rebound anxiety. Alprazolam is also more toxic than other benzodiazepines in cases of overdose, and should not be prescribed to patients at increased risk of suicide, or who use alcohol, opioids, or other sedating drugs. The use of benzodiazepines with opioids doubles the risk of death and respiratory depression, and should be avoided. “Alprazolam should be prescribed primarily in its extended-release formulation for a short duration to minimize misuse liability and only to those with no prior substance use history.”

Well-designed human studies addressing alprazolam’s reinforcing effects and the discontinuation syndrome [withdrawal] are needed, and must consider important issues such as selection of appropriate comparison drug, dose, formulation, and population. Future research should also further investigate the misuse liability of alprazolam XR, and should attempt to clarify the role of carbamazepine, clonidine, other anticonvulsant drugs, and related compounds in the treatment of the alprazolam withdrawal syndrome.

A new study published online on October 19, 2023 examined both the published and unpublished data from five FDA-reviewed trials for Xanax XR. Only three of the five trials were ever published, and all published trials claimed the results of their respective studies were positive. The researchers compared the overall trial results according to the FDA, to the corresponding published literature of the 3 published trials and found only one of the trials was positive. “Publication bias substantially inflates the apparent efficacy of alprazolam XR.”

We found that alprazolam XR may be less effective than the published literature would suggest. According to the published literature, every trial of alprazolam XR found it to be effective. By contrast, according to the FDA, only one of five trials was positive.

The researchers noted where selective reporting of clinical trials undermines the integrity of the evidence base “and deprives clinicians, patients, researchers, and policymakers of accurate data critical for decision-making.” Their study highlighted the value of regulatory data for public health. It brought to light unpublished trial data and provided a more balanced and realistic view of the efficacy of alprazolam XR, compared to what was previously reported. Neuroscience News indicated that publication bias inflated alprazolam’s effectiveness by over 40%!

The senior author of the study, Eric Turner, who is a former FDA reviewer, said clinicians were well aware of the safety issues with alprazolam, but didn’t question its effectiveness. “Our study throws some cold water on the efficacy of this drug. It shows it may be less effective than people have assumed.” He concluded how the study reinforced caution before starting a prescription for alprazolam.

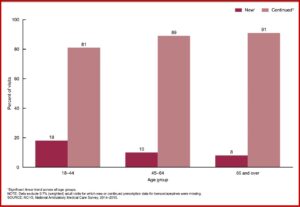

The documentary Take Your Pills: Xanax said after 9/11, prescriptions for antianxiety drugs increased 23% in New York City and 8% nationally. Even before COVID-19, anxiety had overtaken depression as the “diagnosis du jour.” One of the psychiatrists in the documentary said drugs like Xanax were meant to taken short-term—no longer than about a month. But the fact is many people who begin taking a benzodiazepine “will continue to take that for years or even decades.” This is despite that the medication guide for Xanax says it is not known if Xanax is safe and effective to treat anxiety for longer than 4 months or to treat panic disorder for longer than 10 weeks. And it warns you to not stop benzodiazepines suddenly, or you may have “symptoms that can last several weeks to more than 12 months.”

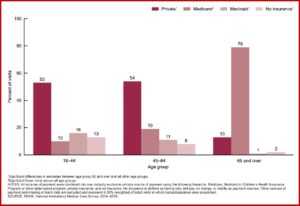

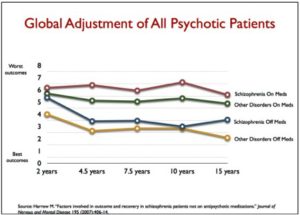

Since direct-to-consumer advertising was approved for prescription drugs and medical devices, patients have come to their doctors telling them what medications they want. And doctors write the prescriptions to avoid a poor evaluation when the patient doesn’t get the drug they were told to “ask your doctor” about. “Medicine has become industrialized to the point where doctors kind of function like workers on an assembly line.” There is also a problem when training doctors about prescribing and using these medications “is not always as robust as one would hope.” Additionally, the typical consumer who asks their doctor for a certain medication is changing.

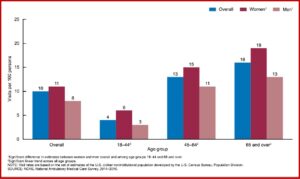

That typical profile of a patient who might be prescribed benzodiazepine is widening. So, whereas it might have been, typically, you know 30 years ago, a middle-aged woman, now we’re seeing younger and younger age groups. We’re seeing very old people are not only being prescribed benzodiazepines, but being kept on them for much longer periods of time.

I’ve written about concerns with the use of benzodiazepine for a while and was pleased to see the Ashton Method for benzodiazepine withdrawal mentioned in Take Your Pills: Xanax. There is a World Benzodiazepine Awareness Day (W-BAD) on July 11th that seeks to raise awareness about iatrogenic, medically caused, benzodiazepine dependence and adverse effects of benzo withdrawal. There is another documentary by Holly Hardman, As Prescribed, which also promotes awareness of benzodiazepine harm: “People don’t realize when they’re given benzodiazepines what’s going to come of it in the end.” Also see, “It Takes Away Your Soul” and Are Benzos Worth it?”

One person in Take Your Pills: Xanax said the only way out of anxiety is to go through it. “What’s going to get you on the other side of the anxiety is to actually go through it and experience it and understand it and make some sort of peace with it.” Another person thought that benzodiazepines like Xanax “erode the resilience that we must rely upon at some point in our lives to manage distress, anxiety, difficult situations.” What is so seductive about benzodiazepines like Xanax is how well they work. We need to remember, “the only way out is through” the anxiety.