Taliban as an IED

The President of Afghanistan, Ashraf Ghani said that without drugs, the Afghan war would have been over. “The heroin is a very important driver of this war.” Former President of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, said the opium problem was the single greatest threat to the long-term security, development and effective governance of Afghanistan. “Either Afghanistan destroys opium or opium will destroy Afghanistan.” The New York Times reported Afghanistan has consistently produced approximately 85% of the world’s opium, despite more than $8 billion spent by the US to eradicate the trade.

Economic factors are driving opium problem in Afghanistan. The United Nations publishes a yearly Human Development Report that “focuses on how human development can be ensured for every one—now and in future.” It uses a summary measure referred to as the Human Development Index (HDI) which assess progress in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and health life (measured by life expectancy), access to learning and knowledge (measured by expected years of schooling), and a decent standard of living (measured by Gross National Income per capita). Afghanistan’s HDI value for 2015 was 0.479, placing it in the lower section for human development at 169 out of 188 countries and territories.

As one of the poorest countries in the world, its 31 million people have an average per capita income of just $800, with 80 percent of its rural population living in poverty. Only 23 percent of Afghans have access to safe drinking water, and only 6 percent to electricity.

Colonel John Glaze wrote the above quote in a report for the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College titled, “Opium and Afghanistan: Reassessing U.S. Counternarcotics Strategy.” Glaze went to note how the high turn on investment from opium poppy cultivation drove an agricultural shift from growing traditional crops, like wheat, corn, barley, rice, to growing opium poppy. “In recent years, many poor farmers have turned to opium poppy cultivation to make a living because of the relatively high rate of return on investment compared to traditional crops. Consequently, Afghanistan’s largest and fastest cash crop is opium.”

Cultivating opium poppy makes powerful economic sense to the impoverished farmers of Afghanistan. It is the easiest crop to grow and the most profitable. Even though the Karzai government made opium poppy cultivation and trafficking illegal in 2002, many farmers, driven by poverty, continue to cultivate opium poppy to provide for their families. Indeed, poverty is the primary reason given by Afghan farmers for choosing to cultivate opium poppy. With a farm gate price of approximately $125 per kilogram for dry opium, an Afghan farmer can make 17 times more profit growing opium poppy—$4,622 per hectare, compared to only $266 per hectare for wheat.Opium poppy is also drought resistant, easy to transport and store, and, unlike many crops, requires no refrigeration and does not spoil. With Afghanistan’s limited irrigation, electricity, roads, and other infrastructure, growing traditional crops can be extremely difficult. In many cases, farmers are simply unable to support their families growing traditional crops; and because most rural farmers are uneducated and illiterate, they have few economically viable alternatives to growing opium poppy.

Business Insider reported an Afghan farmer could be paid $163 for a kilo of raw opium, which looks like a black sap. When the raw opium is refined into heroin, it can be sold for $2,300 to $3,500 per kilo at regional markets. “In Europe it has a wholesale value of about $45,000.” In the past, most of the opium harvest was smuggled out of the country as raw opium and then refined in other countries. But now, officials estimate that half or more of Afghan opium is processed at some level within the country.

“Afghanistan’s economy has thus evolved to the point where it is now highly dependent on opium.” In 2006, revenue from opium cultivation was over $3 billion, more than 35% of the country’s total gross national product (GNP). Opium production has become Afghanistan’s top employer and the principle base of its economy. An estimated 10% of the population are involved in some way with opium cultivation. Yet less than 20% of the $3 billion in profits goes to the farmers that grow the opium.

Traditionally, processing of Afghan’s opium into heroin has taken place outside of Afghanistan; however, in an effort to reap more profits internally, Afghan drug kingpins have stepped up heroin processing within their borders. Heroin processing labs have proliferated in Afghanistan since the late 1990s, particularly in the unstable southern region, further complicating stabilization efforts. With the reemergence of the Taliban and the virtual absence of the rule of law in the countryside, opium production and heroin processing have dramatically increased, especially in the southern province of Helmand. In 2006, opium production in the province increased over 162 percent and now accounts for 42 percent of Afghan’s total opium output. According to the UNODC, the opium situation in the southern provinces is “out of control.”

The refining labs are simple, nondescript huts or caves containing maybe two dozen empty barrels for mixing, sacks or jugs of precursor chemicals, piles of firewood, and a press machine. They also have a generator, a water pump and a long hose to draw water from a nearby well. Afghan police and American Special Forces repeatedly ran into them all over Afghanistan in 2017. “Officials and diplomats are increasingly worried that the labs’ proliferation is one of the most troubling turns yet in the long struggle to end the Taliban insurgency.” Afghanistan’s deputy interior minister in charge of the counternarcotics police estimated his forces destroyed more than 100 of the estimated 400 to 500 labs in the country last year. However, “They can build a lab like this in one day.”

The NYT noted the Taliban has long profited by taxing and providing security for producers and smugglers. “But increasingly, the insurgents are directly getting into every stage of the drug business themselves, rivaling some of the major cartels in the region — and in some places becoming indistinguishable from them.” Refining makes the drug easier to smuggle and dramatically increases the profits for the Taliban. Officials estimate that up to 60% of the Taliban’s income now comes from the drug trade.

In country drug seizures suggest more opium is being processed within Afghanistan. Previously, the amount of opium seized would be five times or more than that of morphine and heroin. “In 2015, for example, about 30,000 kilograms, or 66,000 pounds, of opium was seized, compared with a little over 5,000 kilograms, or 11,000 pounds, of heroin and morphine combined.” But so far in 2107, the seizure numbers have reversed. The amount of heroin and morphine seized is double that of raw opium.

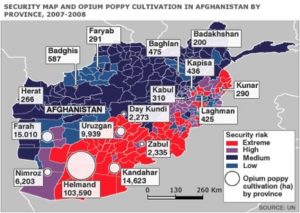

And there seems to be a direct relationship between recent Taliban gains territorially and the drug trade. The Southern Afghan provinces of Helmond, Uruzgan and Kandahar are where much of the country’s opium-poppy production occurred in 2016. They are also in the midst of the country’s provinces with the highest security risks. A senior Afghan official said: “If an illiterate local Taliban commander in Helmand makes a million dollars a month now, what does he gain in time of peace?” See the map below originating with the United Nations Department of Safety and Security.

The Taliban seem to be in the midst of changing from a fundamentalist Sunni political movement into a drug cartel. Their mixture of ideology, power and greed has led to a situation in Afghanistan that can be likened to a political and cultural IED. Afghanistan’s deputy interior minister in charge of the counternarcotics police said the Taliban used the growing insecurity over the past two years to establish more refining labs and move them closer to the opium fields. The Afghan deputy minister of counternarcotics said: “We have to merge these two things together — the counterterrorism and the counternarcotics. It has to go hand in hand, because if you destroy one, it is going to destroy the other.”

The Taliban seem to be in the midst of changing from a fundamentalist Sunni political movement into a drug cartel. Their mixture of ideology, power and greed has led to a situation in Afghanistan that can be likened to a political and cultural IED. Afghanistan’s deputy interior minister in charge of the counternarcotics police said the Taliban used the growing insecurity over the past two years to establish more refining labs and move them closer to the opium fields. The Afghan deputy minister of counternarcotics said: “We have to merge these two things together — the counterterrorism and the counternarcotics. It has to go hand in hand, because if you destroy one, it is going to destroy the other.”

For more on the Taliban and the drug trade, see “Opium and the Taliban.”