The Death of the Chemical Imbalance Theory?

There was an article published recently in the journal Molecular Psychiatry that is getting a lot of attention online. The Hill, Psychology Today, Neuroscience News and other new outlets highlighted an umbrella review by researchers that questioned the serotonin theory of depression and the value treating depression with antidepressants. In an article for The Conversation, two of those researchers wrote, “Our study shows that this view is not supported by scientific evidence. It also calls into question the basis for the use of antidepressants”; and the chemical imbalance theory of depression.

There was an article published recently in the journal Molecular Psychiatry that is getting a lot of attention online. The Hill, Psychology Today, Neuroscience News and other new outlets highlighted an umbrella review by researchers that questioned the serotonin theory of depression and the value treating depression with antidepressants. In an article for The Conversation, two of those researchers wrote, “Our study shows that this view is not supported by scientific evidence. It also calls into question the basis for the use of antidepressants”; and the chemical imbalance theory of depression.

Joanna Moncrieff and Mark Horowitz wrote that the serotonin theory of depression was widely promoted by the pharmaceutical industry in the 1990s with its marketing a then new class of antidepressant medications, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). This strategy became known as the “chemical imbalance theory of depression.” The theory was endorsed by institutions like the American Psychiatric Association. But this has changed, with psychiatrists like Ronald Pies, saying as early as 2011 that, “the chemical imbalance notion was always a kind of urban legend.”

Pies said in another more recent article for Psychiatric Times that he influenced the APA to replace a statement on its public education website that referred to “imbalances in brain chemistry,” with: “While the precise mechanism of action of psychiatric medications is not fully understood, they may beneficially modulate chemical signaling and communication within the brain, which may reduce some symptoms of psychiatric disorders.” The statement quoted by Dr. Pies is in article titled, “What is Psychiatry?”

Moncreiff and Horowitz pointed to another article on the same website, “What is Depression?”, where it said while several factors can play a role in depression—biochemistry, genetics, personality and environment. For biochemistry, it said: “Differences in certain chemicals in the brain may contribute to symptoms of depression.”

Looking at these articles, the chemical imbalance theory may have been weakened, but I don’t think it was defeated. It seems that when medications can “beneficially modulate” and when “differences in certain chemicals” may contribute to symptoms of depression, the imbalance theory is present implicitly. That is why the new study by Moncrieff et al, “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic review of the evidence,” in Molecular Psychiatry is so important.

Despite the fact that the serotonin theory of depression has been so influential, no comprehensive review has yet synthesised the relevant evidence. We conducted an ‘umbrella’ review of the principal areas of relevant research, following the model of a similar review examining prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder. We sought to establish whether the current evidence supports a role for serotonin in the aetiology of depression, and specifically whether depression is associated with indications of lowered serotonin concentrations or activity.

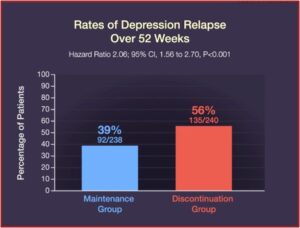

Their comprehensive review indicated there is no convincing evidence that depression is related to or caused by lower serotonin concentrations or activity. Yet surveys suggest 80% or more of the general public believe depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance.’ This belief shapes how people understand their moods, leading to a pessimistic view on what they can expect from treatment. “The idea that depression is the result of a chemical imbalance also influences decisions about whether to take or continue antidepressant medication and may discourage people from discontinuing treatment, potentially leading to lifelong dependence on these drugs.”

Moncrieff and Horowitz said in The Conversation article that it was important for people know the idea that depression as a chemical imbalance is hypothetical. Moreover, we don’t understand what temporarily elevated serotonin or other biochemical changes produced by antidepressants do to the brain. “We conclude that it is impossible to say that taking SSRI antidepressants is worthwhile, or even completely safe.” And yet, the serotonin theory of depression has formed the basis for a significant amount of research over the past few decades.

Along with Benjamin Ang, Moncrieff and Horowitz explored the serotonin theory of depression in the scientific literature in, “Is the chemical imbalance an ‘urban legend’? They noted where the chemical imbalance theory was first proposed in the 1960s, focusing initially on the neurochemical noradrenaline instead of serotonin. “What came to be known as the ‘monoamine hypothesis’ (noradrenaline and serotonin are both classified as monoamines), was stimulated by the belief that certain prescription drugs targeted the basis of mood, particularly drugs that were named ‘antidepressants’.”

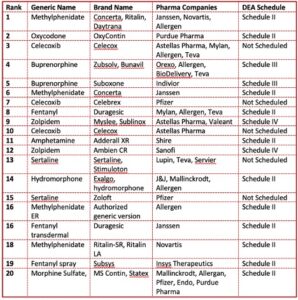

Following the introduction of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), the ‘serotonin hypothesis’ became embedded in the popular and professional consciousness. The pharmaceutical industry promoted the idea that depression was a result of an imbalance or deficiency of serotonin in the brain. SSRIs, which were just being brought to the market, were said to be the ‘magic bullets’ that could reverse this abnormality. In an advertisement for Zoloft, Pfizer said “while the cause is not known, depression may be related to an imbalance of natural chemicals between nerve cells in the brain” and that “prescription Zoloft works to correct this imbalance.”

Ang, Moncrieff and Horowitz more fully documented how the American Psychiatric Association (APA) supported the pharmaceutical company rhetoric from a patient leaflet produced in 2005, which said: “antidepressants may be prescribed to correct imbalances in the levels of chemicals in the brain.” Despite what Dr. Pies said, it seems that the APA did not have many psychiatrists who knew this was a kind of urban legend.

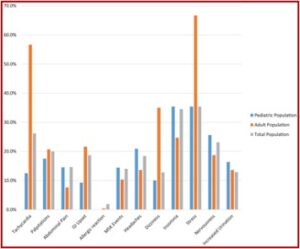

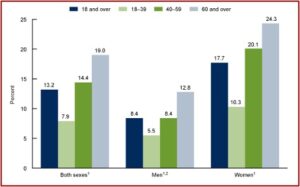

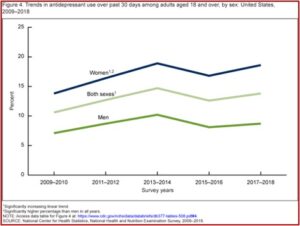

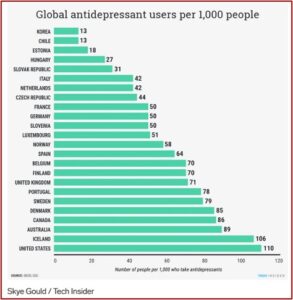

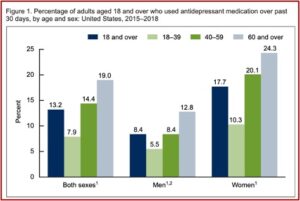

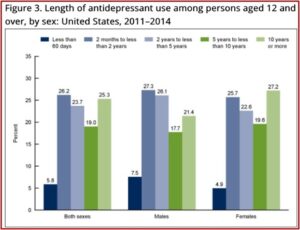

The marketing of SSRIs and the serotonin theory led to a dramatic global increase in their use. Prescriptions in England tripled between 1988 and 1998; and then tripled again between 1998 and 2018. Similar increases took place throughout Europe, with some Eastern European countries where use was previously low, increasing 5-6 times since 2000. In the U.S., antidepressant prescriptions quadrupled between the late 1980s and the mid-2000s.

There is evidence that increasing numbers of people are taking antidepressants on a long-term basis. Research has shown that believing depression is caused by a chemical imbalance is widespread among antidepressant users, encourages people to ask for antidepressants and discourages them from trying to stop.

In 2005, Jeffrey Lacasse and Jonathan Leo published a paper in PLOS Medicine that received a lot of attention. It was the first time the media grasped that the serotonin theory might not be supported by the evidence. Their paper provoked a response by the chair of the FDA psychopharmacology committee, who admitted evidence for a neurochemical deficiency in people with depression was elusive. He thought it could be a ‘useful metaphor,’ but one he would not use with his own patients. While an SSRI may work well with an individual, that “doesn’t prove that there is an underlying imbalance, defect or dysfunction in the person’s serotonin system.”

Responding to a report published by the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, a Church of Scientology organization, Ronald Pies called the chemical imbalance theory an urban legend that no well-informed psychiatrist had ever believed. He claimed the theory was spread by the pharmaceutical industry, and opponents of psychiatry attributed the belief to psychiatrists themselves. A few months later, he wrote an article for Psychiatric Times admitting that there were psychiatrists and other physicians who used the term ‘chemical imbalance’ when explaining psychiatric illness to a patient.

My impression is that most psychiatrists who use this expression feel uncomfortable and a little embarrassed when they do so. It’s a kind of bumper-sticker phrase that saves time, and allows the physician to write out that prescription while feeling that the patient has been “educated.” If you are thinking that this is a little lazy on the doctor’s part, you are right. But to be fair, remember that the doctor is often scrambling to see those other twenty depressed patients in her waiting room. I’m not offering this as an excuse–just an observation.

In 2019 Pies said while some prominent psychiatrists have used the term ‘chemical imbalance’ in public comments about antidepressants, and possibly in their clinical practices, “there was never a unified, concerted effort within American psychiatry to promote a chemical imbalance theory of mental illness.” A good bit of psychiatric opinion follows Pies’ lead and says the idea that depression is caused by brain chemical imbalances is an over-simplified explanation that should not be taken seriously. The attempt by leading psychiatrists to deny that the serotonin theory was ever influential seems to be a tactic to deflect criticism, and allow it to continue in some modified form.

Ang, Moncrieff and Horowitz concluded that during the period 1990-2010, there was considerable coverage of, and support for, the serotonin hypothesis of depression in the psychiatric and psychopharmacological literature. Research papers on the serotonin system were widely cited, and most strongly supported the serotonin theory. Textbooks took a more nuanced approach, but at other points were unreservedly supportive of the theory. Critics of the theory were either ignored or marginalized as antipsychiatry. Yet it seems in 1987 at least one critic, the Irish psychiatrist David Healy, astutely described the neurochemical theory of depression as an exhausted Kuhnian paradigm in “The structure of pharmacological revolutions.” He said it was perpetuated because it served the professional purpose of convincing patients that depression is a biological condition.

Healy was referring to the seminal work by Thomas Kuhn on the philosophy and history of science, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. According to Kuhn, normal science referred to research firmly based on one or more past scientific achievements that a particular scientific community “acknowledges for a time as supplying the foundation for its further practice.” The process of normal science takes place within a paradigm—like the monoamine hypothesis—where research occurs within the context of a scientific community committed to the same rules and standards for scientific practice. “That commitment and the apparent consensus it produces are prerequisites for normal science.”

Any new interpretation of nature, whether a discovery or a theory, emerges first in the mind of one or a few individuals. It is they who first learn to see science and the world differently, and their ability to make the transition is facilitated by two circumstances that are not common to most other members of their profession. Invariably, their attention has been intensely concentrated upon the crisis-provoking problems; usually, in addition, they are men [or women] so young or so new to the crisis-ridden field that practice has committed them less deeply than most of their contemporaries to the world view and rules determined by the old paradigm. How are they able, what must they do, to convert the entire profession or the relevant professional subgroup to their way of seeing science and the world? What causes the group to abandon one tradition of normal research in favor of another?

So in “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic review of the evidence,” by Moncreiff at al, we may be witnessing the death of the old paradigm for depression.

Kuhn went on to observe that the proponents of competing paradigms are always at least slightly at cross-purposes. “Neither side will grant all the non-empirical assumptions that the other needs in order to make its case.” While each may hope to “convert” the other to his or her way of seeing science and its problems, the dispute is not one “that can be resolved by proofs.” Kuhn quoted the theoretical physicist Max Planck who said: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”