Is Science Broken?

Richard Harris has been a science reporter for NPR since 1986. In his recently published book, Rigor Mortis, How Sloppy Science Creates Worthless Cures, Crushes Hope and Wastes Billions, he said that despite the effort, technology, money and passion on the part of many scientists determined to make a difference, “medical research is plagued with unforced and unnecessary errors.” Too often scientists are faced with a choice to do what is best for medical advancement by following the rigorous standards of science, “or they can do what they perceive is necessary to maintain a career in the hypercompetitive environment of academic research.” He said the challenge isn’t in finding the technical fixes. “The much harder challenge is changing the culture and the structure of biomedicine so that scientists don’t have to choose between doing it right and keeping their labs and careers afloat.”

Harris isn’t alone in raising this alarm. In the article “Science is Broken” for Aeon, Siddhartha Roy and Marc Edwards noted how an emphasis on quantity versus quality in scientific research has led to a ‘perverse natural selection,’ and pushed researchers to overemphasize quantity of research in order to compete. “If the hypercompetitive environment also increased the likelihood and frequency of unethical behaviour, the entire scientific enterprise would be eventually cast into doubt.” Such a system is more likely to ‘weed out’ the ethical and altruistic researchers, while “the average scholar can be pressured to engage in unethical practices in order to have or maintain a career.”

They noted how competition for funding has never been more intense, while researchers find themselves in the worse funding environment of the past fifty years. “Between 1997 and 2014, the funding rate for the US National Institutes for Health (NIH) grants fell from 30.5 per cent to 18 per cent.” The grant environment is overly competitive; it is susceptible to reviewer bias “and strongly skewed towards funding agencies’ research agendas.” Roger Kornberg, a Nobel Prize winning biochemist, was quoted as saying: “If the work you propose to do isn’t virtually certain of success, then it won’t be funded.”

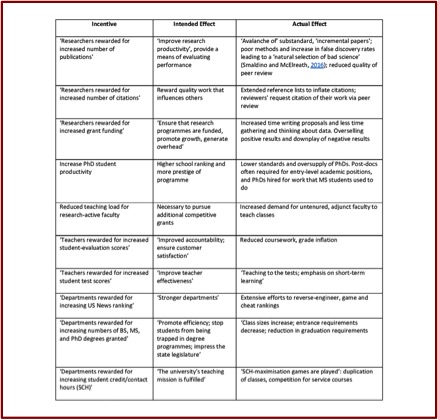

The steady growth of perverse incentives, and their instrumental role in faculty research, hiring and promotion practices, amounts to a systemic dysfunction endangering scientific integrity. There is growing evidence that today’s research publications too frequently suffer from lack of replicability, rely on biased data-sets, apply low or sub-standard statistical methods, fail to guard against researcher biases, and overhype their findings. In other words, an overemphasis on quantity versus quality.

The following Table illustrates how academic incentives become perverse.

“Science is expected to be self-policing and self-correcting.” But Roy and Edwards have come to believe that peverse incentives throughout the system have led academics and researchers to “pretend misconduct does not happen.” Remarkably, science never developed a system for reporting and investigating allegations of research misconduct. When someone alleges misconduct, they don’t have a clear path to follow to report it, and they risk suffering negative professional repercussions. “Today, there are compelling reasons to doubt that science as a whole is self-correcting.”

“Science is expected to be self-policing and self-correcting.” But Roy and Edwards have come to believe that peverse incentives throughout the system have led academics and researchers to “pretend misconduct does not happen.” Remarkably, science never developed a system for reporting and investigating allegations of research misconduct. When someone alleges misconduct, they don’t have a clear path to follow to report it, and they risk suffering negative professional repercussions. “Today, there are compelling reasons to doubt that science as a whole is self-correcting.”

In Rigor Mortis Richard Harris told the story of C. Glenn Begley, who had decided to move on after working at the biotech company Amgen for ten years. Before he left, he decided to take another look at the studies his team had rejected over his time at Amgen because of his team’s failure to replicate the study’s results. “Pharmaceutical companies rely heavily on published research from academic labs … to get ideas for new drugs.” Begley selected fifty-three papers that he thought could have been groundbreaking and lead to important drugs, “if they had panned out.” This time, he asked the scientists who originally published the results to help with his team’s replication efforts.

Surprisingly, “scientific findings were confirmed in only 6 (11%) cases.” Begley and Ellis published the results of this research in an article for the journal Nature, “Drug Development: Raise Standards for Preclinical Cancer Research.” These results were consistent with the findings of a research team at Bayer HealthCare in Germany that reported only “25% of published preclinical studies could be validated to the point at which projects could continue.” An estimate by Leonard Freedman suggested that the cost of untrustworthy preclinical research papers in the U.S. was around $28 billion a year.

Harris said that when Begley and Ellis spoke at conferences, fellow scientists told them: “that we were doing the scientific community a disservice that would decrease research funding.” Privately scientists acknowledged a problem, but wouldn’t voice that publically. “The shocking part was that we said it out loud” and as a result brought the issue of reproducibility to the forefront of the discussion.

Some people call it a “reproducibility crisis.” At issue is not simply that scientists are wasting their time and our tax dollars; misleading results in laboratory research are actually slowing progress in the search for treatments and cures. This work is at the very heart of the advances in medicine. . . . The shock from the Begley and Ellis and Bayer papers wasn’t just that scientists make mistakes. These studies sent the message that errors like that are incredibly common.

Roy and Edwards said: “If we don’t reform the academic scientific-research enterprise, we risk significant disrepute to and public distrust of science. . . . We can no longer afford to pretend that the problem of research misconduct does not exist.” Among the steps they suggested could be taken by scientists themselves to correct this problem were the following. Universities can act to protect the integrity of scientific research and announce steps to reduce so-called perverse incentives and uphold research misconduct policies that discourage unethical behavior. At both the undergraduate and graduate level students should receive instruction on these subjects, “so that they are prepared to act when, not if, they encounter it.” The curriculum should review “real-world pressures, incentives and stresses that can increase the likelihood of research misconduct. “

Finally, and perhaps most simply, in addition to teaching technical skills, PhD programmes themselves should accept that they ought to acknowledge the present reality of perverse incentives, while also fostering character development, and respect for science as a public good, and the critical role of quality science to the future of humankind.

In a review of Rigor Mortis for Washington Monthly Shannon Brownlee said the yearly global cost for biomedical research is $240 billion. The U.S. has the largest investment with $70 billion in commercial and another $40 billion from nonprofits and government—primarily the National Institutes of Health (NIH). More than half of the total resources spent on biomedical research is for basic research, and most of the ideas for studies come from the scientists themselves. She quoted the physicist Richard Feynman, who once said: the first principle of science “is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Much of what ails the bad research that Harris chronicles—the poor lab techniques, incorrect application of statistics, selective reporting of data, and refusal to move away from studies that have been found to be faulty—seems to result from failing to adhere to this golden rule.

It’s not so much that science itself is broken, but the way in which science is practiced has been compromised. Pressure to maintain a career in the competitive world of academic and biotech research has led some researchers to act more like sleight-of-hand artists than true scientists. It’s time to become more aware of the misdirection that perverse incentives embed into the methodology and process of scientific research.