A recent CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report indicated that in 2014 more people in the U.S. died from drug overdoses than any other year on record. There were approximately one and a half times more deaths from drug overdoses than from motor vehicle accidents. Sixty-one percent (28,647) of all drug overdose deaths were from opioids; the rate has tripled since 2000. Drug overdose deaths from heroin have more than tripled in 4 years. The overdose death rate involving synthetic opioids almost doubled between 2013 and 2014.

Drug overdose deaths are up for both men and women; in adults of nearly all age groups. The following table presents data for all overdose deaths in 2013 and 2014; by sex; and by age group. The death rates per 100,000 are given, as is the percentage increase from 2013 to 2014.

|

2013 |

2014 |

% change 2013-2014 |

|||

|

# |

Rate |

# |

Rate |

||

|

All |

43,982 |

13.8 |

47,055 |

14.7 |

6.5% |

|

Male |

26,799 |

17.0 |

28,812 |

18.3 |

7.6% |

|

Female |

17,183 |

10.6 |

18,243 |

11.1 |

4.7% |

|

Age Group (yrs) |

|||||

|

0-14 |

105 |

0.2 |

109 |

0.2 |

0.0% |

|

15-24 |

3,664 |

8.3 |

3,798 |

8.6 |

3.6% |

|

25-34 |

8,947 |

20.9 |

10,055 |

23.1 |

10.5% |

|

35-44 |

9,320 |

23.0 |

10,134 |

25.0 |

8.7% |

|

45-54 |

12,045 |

27.5 |

12,263 |

28.2 |

2.5% |

|

55-64 |

7,551 |

19.2 |

8,122 |

20.3 |

5.7% |

|

≥65 |

2,344 |

5.2 |

2,568 |

5.6 |

7.7% |

The authors of the Report said these figures indicate the opioid overdose epidemic is worsening. That almost seems to be an understatement. In a CDC Press Release Tom Frieden, the Director of the CDC, said the increased number of overdose deaths was alarming. “The opioid epidemic is devastating American families and communities. To curb these trends and save lives, we must help prevent addiction and provide support and treatment to those who suffer from opioid use disorders.” He added how important it was for law enforcement to intensify its efforts to reduce the availability of heroin, illegal fentanyl and other illegal opioids.

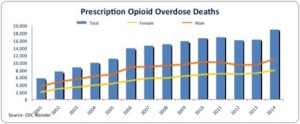

The 2014 data on overdose deaths showed there were two interrelated trends driving the increase: “a 15-year increase in overdose deaths involving prescription opioid pain relievers and a recent surge in illicit opioid overdose deaths, driven largely by heroin.” Natural and semisynthetic opioids, which include oxycodone and hydrocodone, continued to be the most common type of opioid involved in overdose deaths.

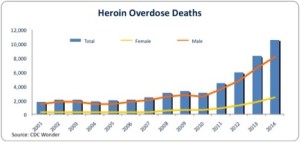

Drug overdose deaths involving heroin continued to climb sharply, with heroin overdoses more than tripling in 4 years. This increase mirrors large increases in heroin use across the country and has been shown to be closely tied to opioid pain reliever misuse and dependence. Past misuse of prescription opioids is the strongest risk factor for heroin initiation and use, specifically among persons who report past-year dependence or abuse. The increased availability of heroin, combined with its relatively low price (compared with diverted prescription opioids) and high purity appear to be major drivers of the upward trend in heroin use and overdose.

The 2014 rates were highest in these five states: West Virginia, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Kentucky and Ohio. There were statistically significant increases in overdose deaths for fourteen states: Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia. Here is an interactive CDC map with this data.

Supporting these findings by the CDC, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reported in “Overdose Death Rates” that there was a 3.4-fold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers and a six-fold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin from 2001 to 2014. The following charts are from the NIDA report.

The CDC pointed to four ways to prevent overdose deaths:

The CDC pointed to four ways to prevent overdose deaths:

- Limit initiation into opioid misuse and addiction. Opioid pain reliever prescribing has quadrupled since 1999. Providing health care professionals with additional tools and information—including safer guidelines for prescribing these drugs—can help them make more informed prescribing decisions.

- Expand access to evidence-based substance use disorder treatment—including Medication-Assisted Treatment—for people who suffer from opioid use disorder.

- Protect people with opioid use disorder by expanding access and use of naloxone—a critical drug that can reverse the symptoms of an opioid overdose and save lives.

- State and local public health agencies, medical examiners and coroners, and law enforcement agencies must work together to improve detection of and response to illicit opioid overdose outbreaks to address this emerging threat to public health and safety.

Overdoses are not just a U.S. problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that globally 69,000 people die from opioid overdose each year. The World Drug Report 2014 estimated thee were 183,000 drug-related deaths worldwide in 2012. The main type of drug implicated in those deaths is opioids.

International Overdose Awareness Day reported that like the U.S. both the UK and Australia have had more deaths due to overdose than road fatalities. Nearly four Australians die each day from overdoses. Ontario, Canada had a 242% increase in fatal opioid overdoses between 1991 and 2010. European Union nations reported 6,100 overdose deaths in 2012. “It is estimated that more than 70,000 lives were lost to drug overdoses in European union countries in the first decade of the 21st Century.”

The CDC recommendations, for the most part, are ones I’d endorse. But like riders attached to big spending bills that have to be passed by Congress, the little phrase in the second recommendation “including Medication-Assisted Treatment” isn’t necessary. Medications like naloxone and naltrexone have a place in the expansion of substance use disorder treatment. But the phrase “medication-assisted treatment” refers to these medications as well as two opioids—methadone and buprenorphine—used in opioid substitution therapy. There is proposed legislation to expand the availability of buprenorphine, the Recovery for Addiction Treatment Act, in committee.

My objection is simple. You don’t “treat” an opioid use disorder with another opioid. You simply substitute dependence on one opioid for another.

I’ve regularly voiced concern over the treatment of opioid dependency with methadone and buprenorphine. Stop and think for a minute. Isn’t it reasonable to find that an individual who was physically addicted to heroin or prescription opioids would improve when they substitute ingesting enough methadone (a Schedule II controlled substance) or buprenorphine (a Schedule III controlled substance) to neutralize their physical withdrawal symptoms? The positive evidence base for opioid substitution treatment is based upon medically assisting an addict to begin using another opioid.

The “evidence-based” effectiveness of opioid “maintenance” treatment involves using these acknowledged addictive substances (methadone and burprenorphine) for weeks and even years to manage or stabilize an addiction to other opioids. There is more information on this issue in other articles I’ve written: “The Seduction of Opioid Substitution,” “Another Head for the Hydra,” and “A Double-Edged Drug.”

Another one of the drug types showing an increase in overdose deaths since 2001 in NIDA’s “Overdose Death Rates” was benzodiazepines. There has been a five-fold increase in the total number of deaths related to benzodiazepines. “Benzos” combined with opioids like methadone and buprenorphine have a synergistic effect and will give the person a heroin-like euphoria with the right drug cocktail. They also contribute to the higher rates of accidental overdose deaths. Expect the opioid overdose death rates to continue to rise even if the expansion of opioid substitution curtails overdose deaths from heroin.